All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Clarkson Potter/Publishers, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

www.clarksonpotter.com

CLARKSON POTTER is a trademark and POTTER with colophon is a registered trademark of Random House, Inc.

Photographs at courtesy of the author.

Photographs at reprinted courtesy of Swee Phuah.

Image reprinted courtesy of Yoshikazu Tsuno/AFP/Getty Images.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available upon request.

Despite a lack of natural ability, I did have the one element necessary to all early creativity: navet, that fabulous quality that keeps you from knowing just how unsuited you are for what you are about to do.

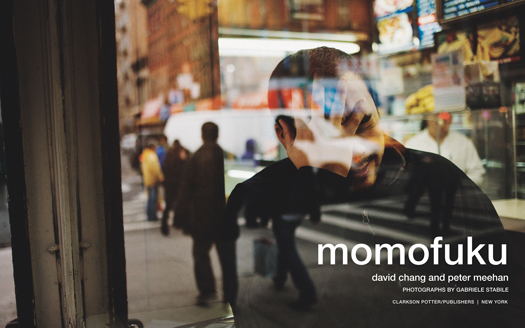

introduction

What is Momofuku? Thats a tough one.

Momofuku is a restaurant group based in the East Village in New York City. The Momofuku restaurants are irrefutably casual places with music blaring at all hours of the day, with the kitchens opened and exposed, with backless stools to sit on, and with framed John McEnroe Nike ads passing as decor. Momofuku is the anti-restaurant.

Momofuku, the name, is Japanese; David Chang, the owner and head chef, is Korean American; the food eludes easy, or really any, classification. There is a focus on good technique, on seasonality and sustainability, on intelligent and informed creativity. But it is deliciousness by any means that theyre really going for. Chang has called it bad pseudo-fusion cuisine, by which I take him to mean that anyone who needs to ask probably wouldnt understand. Using a quote from Wolfgang Puck to describe the restaurants cooking, hes made the argument that Momofuku tries to serve delicious American food. Seems like the most useful descriptor to me. Where else would labne and ssmjang and Sichuan peppercorns and poached rhubarb all end up in the same kitchen?

For people living in or attuned to the bubble world that is the post-millennial restaurant scene in America, Momofuku is a kinetic, hypegenerating buzz magnet the likes of which has rarely, if ever, been seen. And few chefs, now or before, have gotten the golden shower of awards, attention, and praise that Chang has, especially at his age, especially while unapologetically pursuing a path that so aggressively flaunts convention.

Momofuku is, from the inside looking out, like a gang, or maybe a pirate crew. A way of life lived under a flag with an orange peach on it instead of a Jolly Roger. A collective, but not some idyllic hippie thing; instead a group of humble, talented, and dedicated people working as a whole to make their restaurants better every day, to revisit and re-create their menus, to always, always be pushing ahead. Complacency and contentedness are scarce commodities at Momofuku.

And me? I hated Momofuku Noodle Bar the first time I went there. Hated it.

It was late 2003. I was new to my job reviewing cheap restaurants for the New York Times; I was more enthralled with the ideal of authenticity than I am now, six years later. But if those were my problems, those were Momofukus problems, too: it took the place a while to shake off the newness and settle into a groove, for Chang and Joaquin Baca to loosen themselves from the conceptual shackles theyd opened with, to just start cooking whatever they wanted instead of laboring under the constraints of being a noodle barpropagandist-in-chief Changs way of not calling his ramen shop a ramen shopand becoming Noodle Bar as it exists today.

And did they change it. My editor urged me to go back and check the place out about eight months into its life. And though I didnt think Id like it any more than I had the first time around, thats what the job was all about. And that second meal at Noodle Bar just killed me. It was so fucking good, and not in some lightbulby way, but because it was gutsy. It was honest. It was delicious, that least descriptive of all food words, but it was and it was so in a way that made me want more.

After I reviewed Momofuku, I started eating there regularly, going every Saturday at noon, before the lines formed and the crowds crowded. (Chang still puzzles at the little groups that assemble outside his restaurants in the minutes before they flip over the open sign, protesting that they should go home and order some Chinese food if theyre hungry. But hes like that.)

Mark Bittman, who wrote How to Cook Everything and was my lord and master before he helped me land the gig at the Times, was my regular lunch companion. Eventually he introduced me to Chang. We said hi and that was about it.

Then, one night in Brooklyn a few weeks later, I was at a club called Warsaw seeing The Hold Steady when I felt this meaty hand slap me on the back. I turned around and there was Chang, probably as toasted as I was, with a beer extended toward me and the question, which he yelled over the music, Are we going to pretend like we dont know each other?

Were the same age, Chang and I, and we were standing there at the same show, and he had a cold beer in his hand. I took it. Thats how we got to knowing each other.

Wed grab a beer every once in a while in the months after that, bitch about whatever, eat cheap Chinese or Korean food. At some point Dave asked me to help him write this book. I didnt see how I could say no.

It was those flavors. That pop. The fucking pork buns. The way Chang and company put together combinations that read like muddy dead endsBrussels sprouts and kimchi, really?but slapped me awake every time I ate them. Who wouldnt want to know how to make this stuff? Who wouldnt want to have the recipes for this food that was upending the hegemony and balance of the New York restaurant world? Who wouldnt jump at the chance to work with the kitchen there, to try and ferret out what they were doing to make the food so goddamn good?

There was also the unlikely story of Momofukus genesis, evolution, and ascension. Its been told many times, by many good writersin