My sincere thanks to all who contributed to this book, in particular; Ambassador Dr. and Mrs. Fred Bieri of Switzerland; The Cultural Counselor of the Indonesian Embassy, Washington D.C.; The Museum of Ethnology, Basel, Switzerland; The Rhsska Konstsljdmuseet, Gteborg, Sweden; Mr. Grant Cole of Glen Falls, N.Y., for his photography, and last but not least, to my husband and son.

Acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to use illustrations included in this book.

Ambassador Fred Bieri, Swiss Embassy, Djarkarta: Figs. 11, 13, 15, 16, 19, 20. Batiks from Java, Royal Tropical Institute, Amsterdam: Figs. 4-10, 25. Embassy of Indonesia, Washington, D.C.: Figs. 12, 14, 17, 18. Museum fur Volkerkunde, Basel, Switzerland: Figs. 1-3. Rhsska Konstsljdmuseet, Gteborg, Sweden: Fig. 62. Smithsonian Institute, Washington, D.C: Fig. 58. Standard Oil (N.J.): Fig. 21.

The HISTORY OF BATIK

Batik is so old a craft that its true origin has never been deter- THE mined, but it can safely be presumed to be at least 2,000 years old. Archaeological findings prove that the people of Egypt and Persia used to wear batiked garments, and the same can be said of the people of India, China, Japan, and most countries in the OF East. In Africa, batik occurs in the symmetrical tribal patterns; in India, in the ancient paisley pattern; and in China and Japan it has lent itself perfectly to delicate Oriental designs.

There are many theories to explain the possible origin of batik, though none leaves us completely without doubt. If it originated in Egypt, it may easily have spread to Africa and Persia and subsequently all the way to the East, adapting itself to the individual touch of each nation. In contrast, J. A. Loeber states in his book on batik, Das Batiken, eine Blute des indonesischen Kunstlebens, that it is more likely to have originated in the Indian Archipelago. History tells of people of that area wearing white clothes, dyeing them blue as they became dirty, and discarding them only when they had shredded into rags. The natives of Flores used rice starch to extend the lifetime of their clothes, and since we know for sure that rice starch was the fore-runner of wax in the development of batik, Mr. Loeber's theory is certainly supported by quite a few facts.

Wherever we turn in search of that ancient craft, we always seem to lose the trail in the mist of unrecorded history. Some archaeological findings of batiks trace back to the 10th century. Ruins of a temple on Java dating back to about the 13th century show fragments of stone figures wearing garments decorated with motifs strongly resembling the sarong of the 20th century in style and decoration. On the grounds of this evidence, by the 12th century batik had reached Java, where it established itself as an important part of Indonesian culture and economy.

In the book, Arts and Crafts in Indonesia, (Ministry of Information, Djakarta) the word "batik," as such, is derived from ambatik, meaning a cloth of little dots. A "little bit" or a "little dot" means tik, which once again resembles the Javanese word tritic or taritic.

At first, batik was applied to homemade cottons and calico but with Marco Polo and probably even before him, some fine muslin reached the Oriental bazaars. The finely woven quality of this cloth was perfect for batik as well as the climate.

As each house of aristocracy has its coat of arms and each clan of Scotland its own tartan, so the nobility of Java introduced their own motifs and colors. According to the book The Art of Batik, (R. Soeprapto) Sultan Hanjokrikusmo, who ruled from 1613 to 1645, was very fond of the craft and created many beautiful and deeply symbolic designs.

At first batik was merely a pastime of the ladies of the Javanese courts, but it became a matter of social status to wear batiked sarongs to display one's artistry in design and color. In order to keep the wardrobes well stocked, all ladies of the court were soon engaged in the decoration of their robes. As time passed, the ladies-in-waiting and even the servants had to give a helping hand, and batik continued to grow in popularity. It had become a national costume worn by men and women alike.

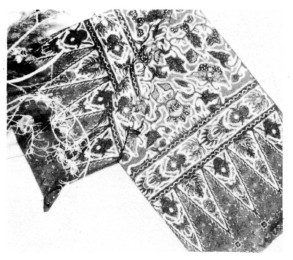

Man's smock. African batik on cotton

Cotton batik. Pa-Miao tribe. China

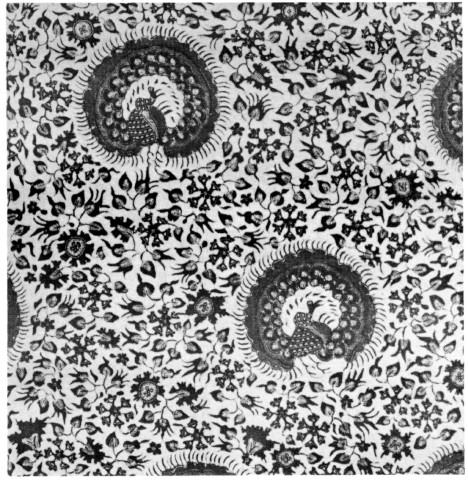

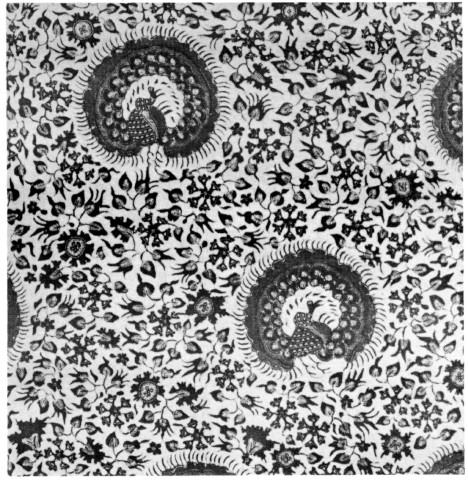

All the natural things surrounding the Javanese, such as birds, flowers, fruits, foliage, butterflies, fish, and shells, were used in the most elaborate motifs to embellish their sarongs, kains, kembangs, and slendangs. Religious law, however, forbids the Moslem to represent any living being, so the peacock and eagle, those very royal creatures, and the elephant and all other animals had to be stylized to obey that provision. There were hundreds of patterns, many of which assumed their own names and withstood the changes of time and outside influence for centuries. Principal basic patterns are the kawung, parang, tjeplok, and semen.

Basic Patterns

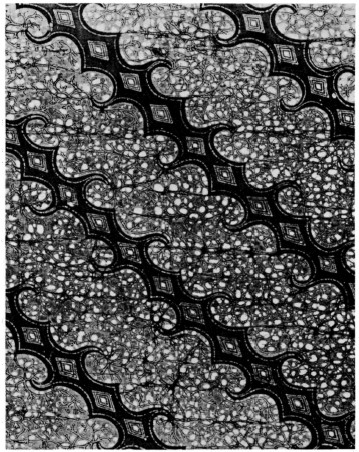

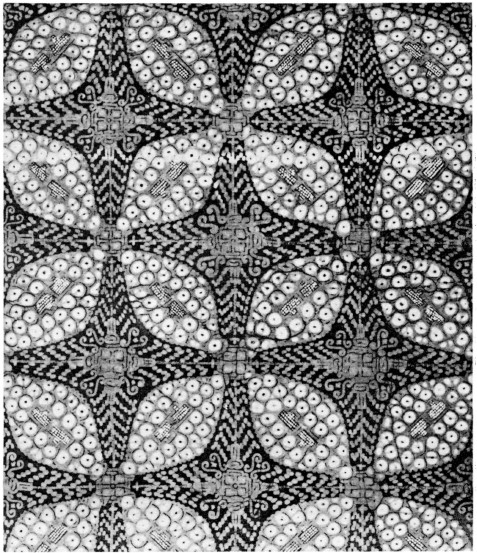

Batik Kemban with ornamental spider border

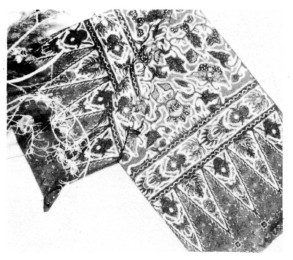

Stylised peacock pattern from Semarang

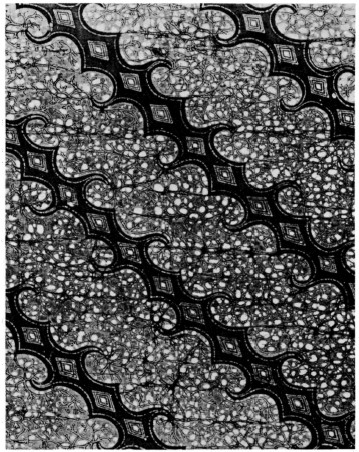

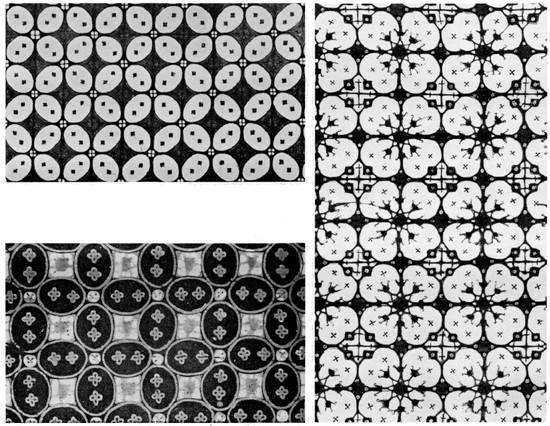

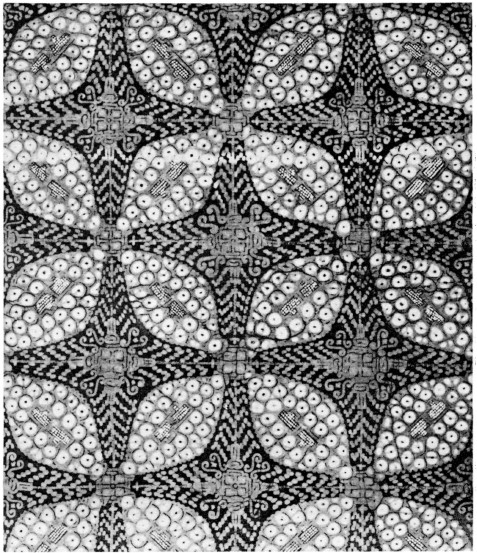

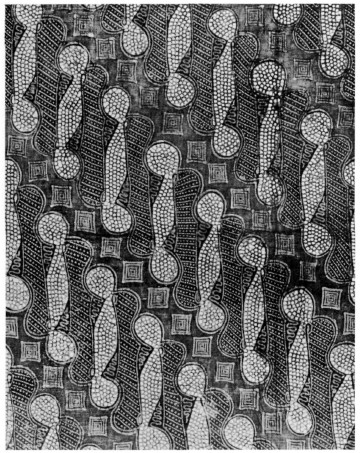

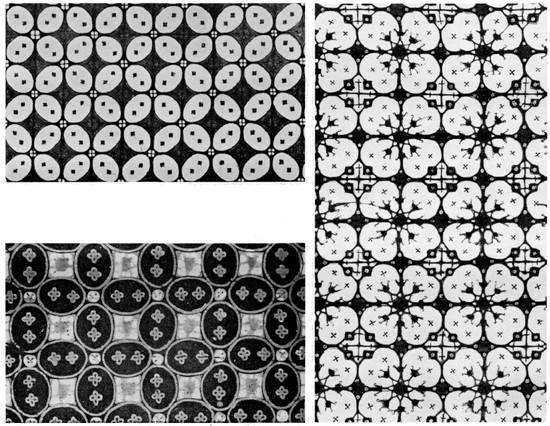

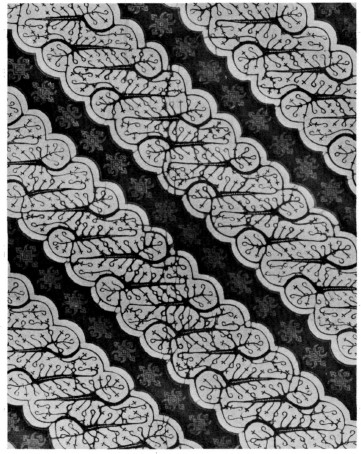

Basic Kawung Patterns

The kawung is a classic example of an ancient pattern that originated in Central Java. According to the natives, the ovals in the design represent the fruit of the kapok tree, the areng leaf, and the like. The characteristic of the kawung pattern vs the arrangement of the ovals or ellipses in groups of four, embellished with tiny floral motifs. The kawung can be traced back to 1239 A.D. when it appeared on a stone ganeca from Kediri

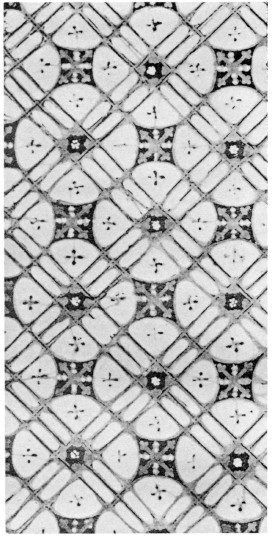

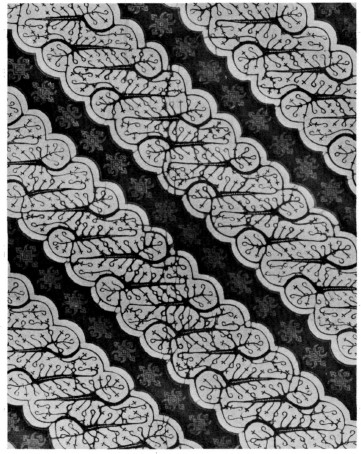

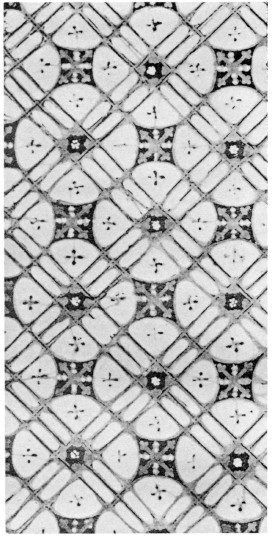

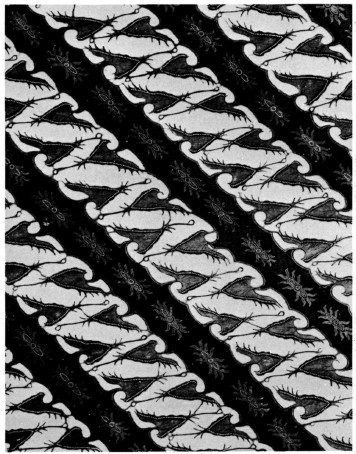

6 The word 'parang' may literally translated as 'rugged rock' or even 'chopping knife.' The pattern, which originated in Solo, central Parang Java, can always be recognised by its diagonal craggy lines, or stripes, often with a scalloped border. The wider stripes contain small geometrical design of floral motif

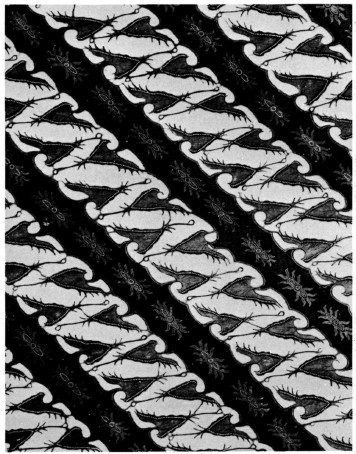

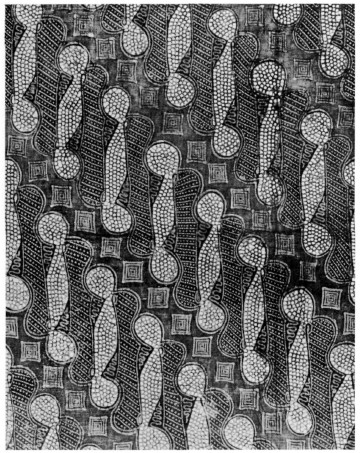

Basic Parang Patterns

Parang from central Java. This design is used on stoles worn by girl dancers