Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

Copyright 2020 by Kenneth Robison

All rights reserved

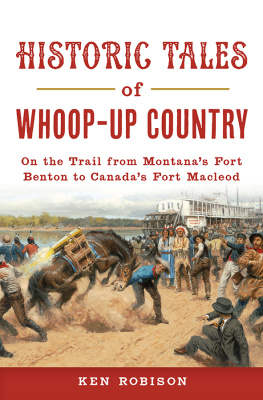

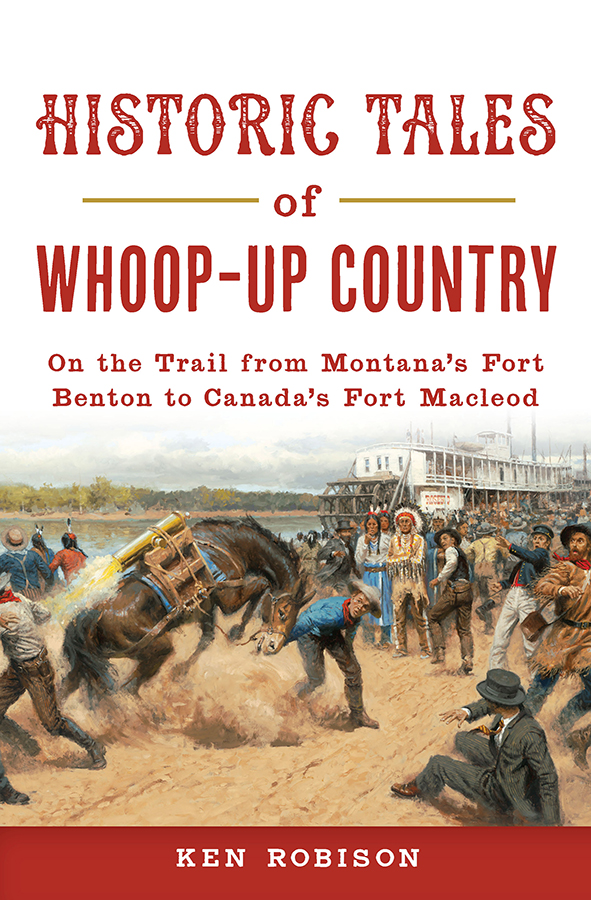

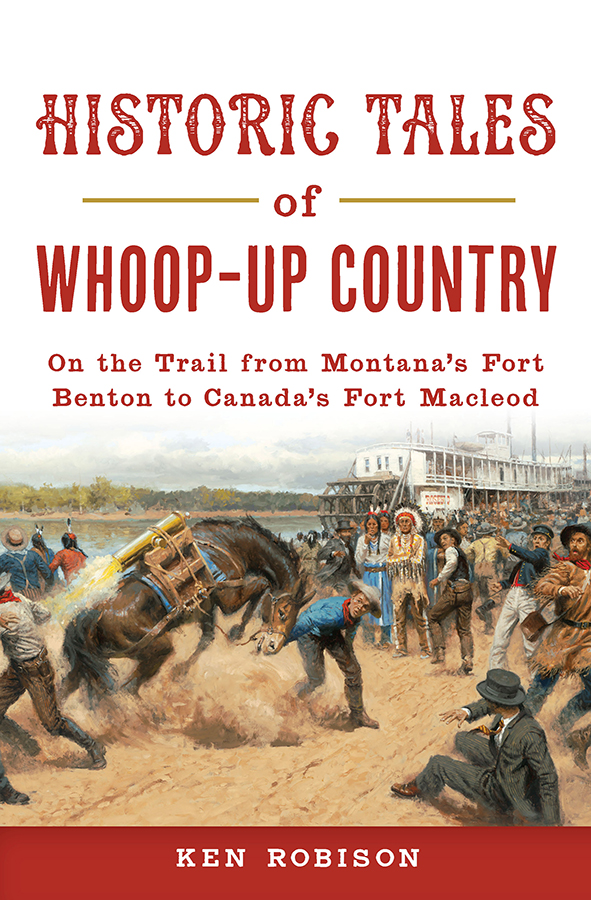

Front cover: A Hot Time in Fort Benton, painted by Andy Thomas, depicts a true incident in Fort Benton in 1865 when a four-pound mountain howitzer strapped to the back of a mule was fired with surprising results while Native Americans looked on in amazement. Courtesy of Andy Thomas.

First published 2020

E-Book edition 2020

ISBN 978.1.43967.138.2

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020940196

Print Edition ISBN 978.1.46714.644.9

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

To Montanas pioneers and indigenous peoples and our Canadian neighbors across the Medicine Line for our shared history and heritage.

To founder John G. Lepley and the Fort Benton River & Plains Societypast, present and futurefor presenting history with verve.

To our Whoop-Up friends across the Medicine Line, Doren Degenstein, Gord Tolton, Mike Bruised Head and all:

May the saddest day of your future be no worse than the happiest day of your past.

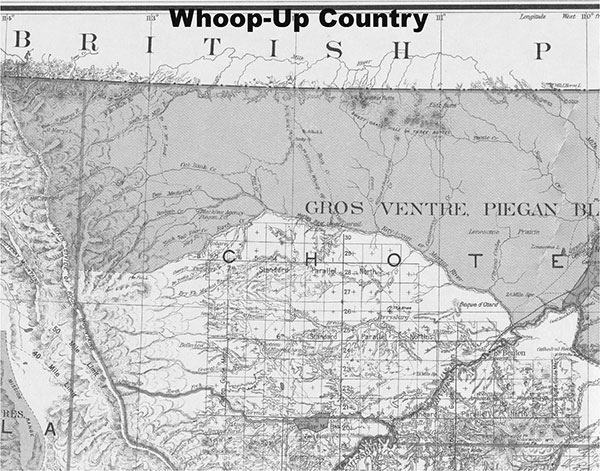

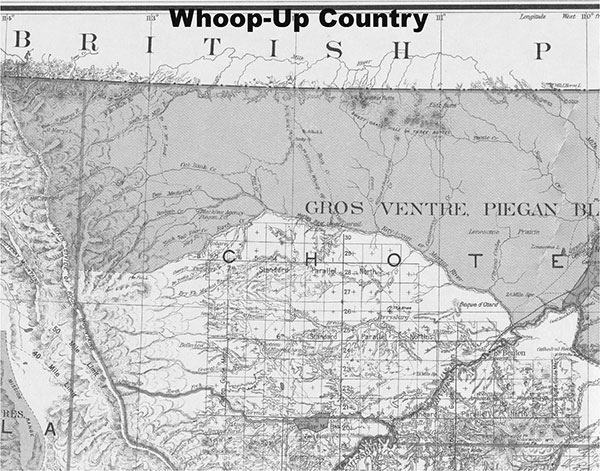

Whoop-Up Country from Fort Benton to the Rockies, from Sun River to the British Possessions. Montana Government Land Office Map, 1887. Map reproduction courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Like spokes on a wagon wheel, trails and rivers radiate in every direction from the Birthplace of Montana. Leading from the west over the great falls to that birthplace, Fort Benton, flows the natural highway, the Missouri River, making this distant frontier town the worlds innermost port and the commercial center for Montana Territory in the 1860s and 70s. Radiating out from Fort Benton were many trails: the Mullan Military Wagon Road, Northern Overland Trail, Cow Island Trail, Camp Cooke Trail, Graham Wagon Road and others. No trail was more important or notorious in its day than the Whoop-Up Trail, yet today this first international highway in the Northwest is largely forgotten. On this 150th anniversary, this is the story of the Whoop-Up Trail and Fort Whoop-Up and the prairie lands through which the trail passes, known as Whoop-Up Country. The Whoop-Up Trail extends from Fort Benton, northwest across the Medicine Linethe then unmarked and ill-defined international borderinto western British America, todays Canadian provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan. Fort Benton is the birthplace of Whoop-Up Country.

The year 2020 marks the 150th anniversary of the birth of the fort, the trail and the country that bear the colorful name Whoop-Up. It all began in 1870 when the stage was set by the withdrawal of the Hudson Bay Companys monopoly from southwestern Canada the previous year. For fifteen years, from 1870 to 1885, trade goods, supplies, immigrants and adventurers came up the mighty Missouri River to Fort Benton by steamboat for transfer to overland freight wagons to follow a trail that assumed legendary fame and notoriety. Whoop-Up Country formed along the trail that passed through the broad, rolling prairie lands between Fort Benton, Montana Territory, northward across the Medicine Line into the newly formed Canadian North West Territory and westward to the Rocky Mountains.

WHOOP-UP TRAIL

Into the law-and-order vacuum left by the Hudson Bay Company, with no civil or military authorities and across an ill-defined border, in mid-January 1870, American traders John J. Healy and Alfred B. Hamilton commenced building a trading post, named Fort Hamilton, at the junction of the Belly and St. Mary Rivers (near todays Lethbridge) in the heart of Blackfoot Indian country. The post, soon known as Fort Whoop-Up, was the first and foremost of a chain of trading posts, often called whisky forts, where Fort Benton free traders bartered a wide range of trade goodsrifles, ammunition, blankets, tobacco, sugar, knives, beads and whiskywith the Blackfoot and other Indian nations for bison robes, hides, furs and pelts. The trade goods were hauled in large Murphy wagons, by oxen or mules, along the two-hundred-mile trail from Fort Benton. For five years, from 1870 until 1875, this was a lucrative business, and the most skilled traders made small fortunes.

The riches to be made and the absence of law and order drew a wide mix of humanity, saints and sinners, leading to incidents and conflicts culminating in a battle in the Cypress Hills between Fort Benton traders and North Assiniboine (Nakota)the Cypress Hills Massacre. Responding to complaints from both sides of the border, the Canadian government in 1873 at last formed the North West Mounted Police (todays Royal Canadian Mounted Police) and sent them west the following year to establish law and order, close down the whisky trade and coerce the free traders back across the border into Montana. The result was lively and surprising.

With the arrival of the Mounted Police in the fall of 1874, Fort Benton merchants and traders realized that even more money could be made supplying the Mounted Police and encouraging the growth of frontier communities in what became the provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan. So, as the Mounted Police closed down the whisky trading posts, the number of freight wagons on the Whoop-Up Trail from Fort Benton across the border actually increased. For the next decade, until the arrival of the Canadian Pacific Railroad in the prairie provinces in 1883, millions of dollars were made by Fort Benton merchant princes like I.G. Baker & Co. and T.C. Power & Bro. During these years, about one-third of the massive flow of cargo coming up the Missouri River to the Fort Benton levee was hauled by overland freight wagons over the Whoop-Up Trail to the newly formed Dominion of Canada.

In the postCivil War era of the late 1860s, Fort Benton became home to a transient population, adventurers with wanderlust seeking opportunity. The frontier riverport boomed during steamboating season in the spring and summer with steamers arriving heavily loaded with passengers and freight, leaving mountains of cargo on the levee, and a massive overland freighting mix of wagons, oxen, mules and bullwhackers. Yet the town became nearly dormant during the winter. In those years, Fort Benton was a rough town with saloons and joints in the Bloodiest Block in the West operating day and night, a town of free-flowing whisky and quick triggersso bloody that in 1869 the Blackfeet Indian Agency had to be removed ninety miles westward up the Teton River, near todays town of Choteau.

Fort Benton was a melting pot bordering on a powder keg. Many of these men had seen Civil War service, both North and South, and not a few had killed before. Many had Native wives, and it was well into the 1870s before the presence of White women became substantial. The remoteness and minimal law and order attracted many southerners, including Confederate soldiers and adventurous African Americans, many working on steamboats, and others trying out their freedom. They were joined by the Chinese who left the gold fields of southwestern Montana to operate restaurants, wash houses and opium dens. The Irish joined local southerners to keep Democrats in power politically throughout the new territory. Among the Irish in Fort Benton were an increasing number of Fenians, some coming directly from Fenian invasions of Canada, and all bringing their hatred for all things British. Beginning in 1869, a depleted U.S. Army infantry company was stationed in a newly formed Fort Benton Military District to provide a semblance of security.

Next page