Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2017 by Byron Browne

All rights reserved

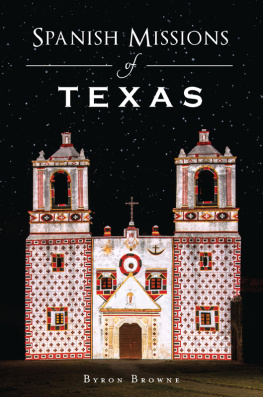

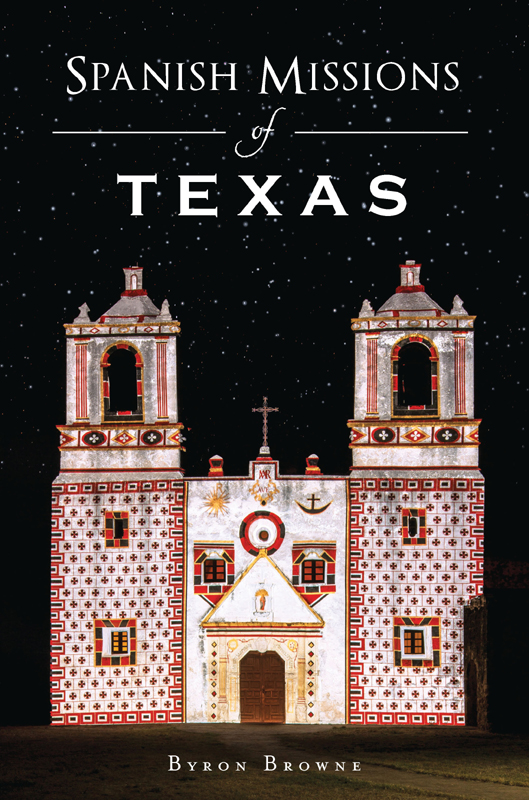

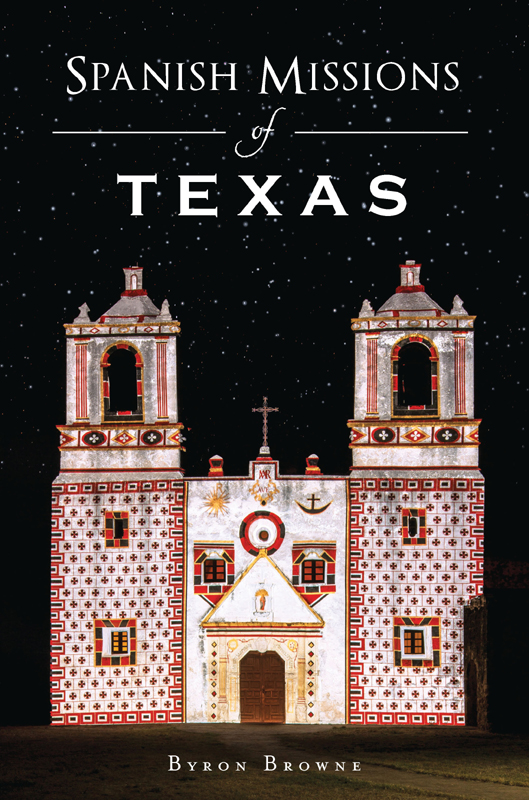

Front cover: Mission Concepcion Restored by Light by Laura Hernandez.

First published 2017

e-book edition 2017

ISBN 978.1.43965.930.4

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016950694

print edition ISBN 978.1.46713.630.3

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

This book is dedicated to Giovanni di Pietro di Bernardone, whose singular vision has compelled millions to try and find new methods of bridging those insufferable chasms between us all.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

In no way does this book intend to shed any new light or bring into sharper focus new information about the Spanish colonial period in Texas. Most of that work was accomplished 100 to 150 years ago by historians and scholars with more resources. However, this writer is forever indebted to those who went in search of and translated the old Spanish records, journals, inventories and diaries. Without their previous work, much of this book would have been erroneous and, perhaps, dull. Scholars such as Casteeda, Bolton, Weddle, Habig and Dunn, to name a few, are owed a debt by all of us for their tireless work. Also, those Franciscans and soldiers who maintained their journals and diaries, all while suffering the elements and attacks and being deprived of wants and needsto these brave men I feel we are all indebted, perhaps in a way we do not yet realize. Men such as Bernal Daz del Castillo and Fathers Espinosa and Morfi chronicled their times, somehow knowing that what they were engaged in was worthy of a place in history. To all of these men I am eternally grateful, as I believe all should be who take an interest in the past. Father Espinosa, the Julius Caesar of the Spanish Colonial Period, surely was aware of the Ciceronian quote Nescire autem quid ante quam natus sis acciderit, id est semper esse puerum (To not know what occurred before you were born is to be forever a child).

Many others have helped make the writing of this book possible, not the least my wife, Angie, who was more patient than I knew possible during all the late nights, very early mornings and missed appointments. To her I am forever obliged.

Similarly, as always, I am indebted to my son, Taylor, for his never-yielding encouragement and optimism.

Of the many others who offered their time and effort to this work, I am very grateful not only to have worked with them but simply to have shared their company for a few moments: Melissa Gonzales, formerly of the Witte Museum; Claudia Rivers, curator of the Special Archives Collection for the University of Texas at El Paso, and her excellent staff; Father David Garcia; Brother Ed Loch at the Diocese at San Antonio; Jared Ramirez with the Goliad State Park; Dr. Michael Strutt; Corey Snyder, a colleague with a kindred interest; Mrs. Marybeth Tomka, the head of collections at the Texas Archaeological Research Laboratory; Mr. Vincent Huzar, for his time and invaluable information; and the staff at the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History at the University of Texas at Austin.

There are, of course, many others who, in some way, contributed to this books development, and I thank them all. If I have overlooked anyone obvious, please realize any oversight was an error of fatigue, not conscience.

INTRODUCTION

When faced with the complexity and magnitude of this subject, I confess that, in a way like Father Massanet, I was tempted to leave it as I had found itunbounded, overgrown, wild and teeming with potential injury. The amount of work already completed on the Spanish missions in the United States is overwhelming. Dozens of missions and presidios stud the American landscape, from the Carolinas to California. Each has had dozens of writers and photographers pursuing their story for over two centuries. And each includes thousands of letters, invoices, requests, inventories and the ubiquitous complaints of the Franciscan missionaries, Spanish soldiers and regional politicians that fill hundreds of boxes at a few dozen institutions in the Southwest United States, Mexico and Spain. However, the subject is too intriguing to leave untried. Because the work was not yet completed, previous authors have not dealt with the restoration and reconstruction efforts that so many have labored over for so long. This book makes a small attempt to update the reader on the status of these Texas missions as they rest, today, in the twenty-first century.

The sixteenth century promised adventure and wealth for the Spanish crown. However, the errant journeys of Cabeza de Vaca, one of the four survivors of the Narvez expedition of 152728, procured a marvelously horrific narrative and yielded little in the way of riches for the Spanish government. Subsequent explorations by Vzquez de Coronado, de Soto, Espejo, lvarez de Pieda, Moscoso and even Oate ended in much the same manner: defeat brought about through disease, exposure to the elements or lack of resources. The vaunted Seven Cities of Cibola, the fabled Seven Islands of Antille and Gran Quivira all were to exist and contain more gold and silver than the Spanish vault could maintain. For nearly a century, conquistadors and explorers ranged through an often fruitless and hostile territory that yielded very little as far as the crown was concerned. In 1629, however, a preternatural event turned the heads of the Spanish government and the hearts of its Franciscan missionaries.

Her name was Mara Coronel y de Arana. She was born in 1602 and raised in Agreda, a town in the north central portion of Spain. Agreda was known as a community where Christians, Arabs and Jews lived and worked together. At the age of sixteen, she took her orders; the family home, after a few years of wrangling from her father, was transformed into a convent. The entire immediate family devoted themselves to the principles and dictates of St. Francis. Akin to the brown, dun habits worn by the Franciscan brothers, the sisters of the Convent of the Immaculate Conception wore a white-and-blue habit. Once cloistered, Mara assumed the name Sister Mara de Jess de Agreda. Beginning in 1620 and continuing for eleven years, Sister Mara is said to have had dreams of bilocation, wherein her spirit traveled to west Texas and eastern New Mexico to educate the natives in the ways of the Catholic faith. Indeed, in the summer of 1629, a delegation of the Jumano tribe walked to the Friary San Antonio de la Isleta in New Mexico to ask for more information regarding the lessons they had received. The custos (Latin for guardian) of the friary, Father Alonso de Benavides, understandably perplexed, pressed the Indians for more information. They related how the Lady in Blue had given them instruction in the Christian faith for several years in their own language and was the personage who had directed them to the friary for further lessons and to ask for baptism. (Benavides mentions this episode in his extraordinary pamphlet

Next page