Table of Contents

Introduction

On a cool spring day, the three of us settled back into cushions in Ingrids cozy living room, catching up after a long time. Five years earlier, we had worked together in the same Seattle publishing office. One of our final projects had been a literary anthology on solo travel, A Woman Alone, which we had coedited and published in 2001. Now we lived in different cities and our paths had diverged some, yet the idea to publish a companion volume had prompted us to schedule a longoverdue get-together. After wed swapped stories and photos of our kids, the conversation turned from family to travel.

We discovered that the passage of time had brought changes to our lives and to our perspectives on travel. Christina shared that after the birth of her first child, she had started a new job that had given her the opportunity to do regular solo stints in major cities around the world. Once upon a time, shed made this kind of travel her greatest goal, pinching pennies to get herself anywhere new and different. Ironically, it was only once she had a family and was more interested in nesting that it was suddenly thrust upon her on a regular basis. Travel is so different now, Christina commented. Where once I took such pleasure in preparing for every detail of a trip ahead of time, I am now so engulfed by anxiety in the anticipation of these trips that they almost do me in. My mind is a flurry of to-do lists running nonstop, day and night.

All of us are mothers and could relate to Christinas travel anxiety, as well as that blessed point of no return, as we dubbed itthe moment when you are finally settled into your tiny plane seat, when there is nothing you can do for anyone anymore. How jarring and unsettling that longed-for moment can be. In a world full of people and demands, the sudden emptiness of being alone can be disquieting, yet also liberating, as we slowly remember again who we are as individuals.

As we discussed the strangeness of leaving the cluttered life and cluttered mind behind, we were struck once again by the fact that solo travel takes many forms at different times in our livesand ultimately fulfills different needs. We discovered that we had once naively considered solo travel to be primarily about satisfying the soul-searching, confidence-building needs of our twenties. The focus was on proving ourselves, developing resourcefulness, getting lost, and finding our way back. But what we hadnt realized then was that the solo experience offers unique insight and perspective at any age, under any number of circumstances, both expected and unexpected. Even the confident, resourceful, and independent traveler has much to gain from the solitary journeywhether its perspective on a life left behind, unexpected connections with locals, insights into how individual relationships are separate from the realm of global politics, or the simple and pure joy of a few anonymous days of not having to organize our hours around the needs of anyone else.

We also discussed the nature of foreign travel as Americans, and as solo women, in a world profoundly affected by the events of 9/11 and its aftermath. How it can feel like a political act, almost a patriotic duty, to go abroad. We had all traveled since 9/11, as had many of our friends and family members, and what we all found was a world different in many ways from the one portrayed by our fear-driven media. No doubt the worlds hot spots are indeed hot spots, yet in our experience people the world over are eager to engage with Americans. We were reminded in these real-world exchanges that people are able to separate the actions of governments from those of individuals. What we found in our own experienceand what we read in the submissions we received and, ultimately, in many stories we selectedran counter to what we had been hearing every day on our televisions and reading on the front page.

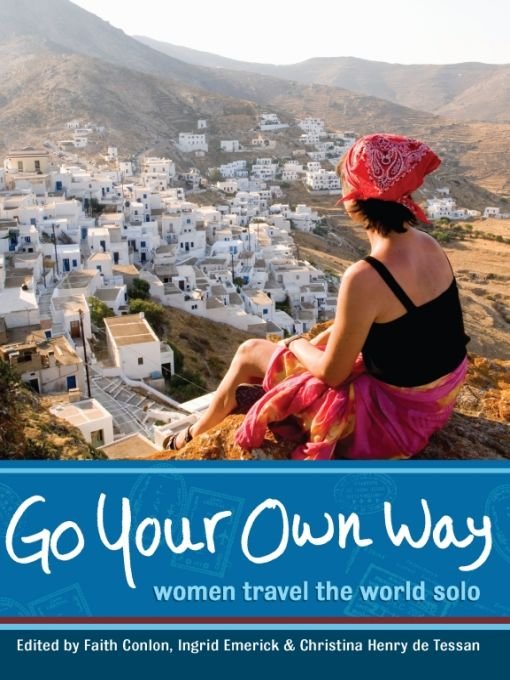

All of these considerations, personal and political, made us realize that the time was ripe to pursue a sequel to A Woman Alone. First and foremost, we wanted to inspire women to get out and travel. After all, the best way to quell fear, build bridges between cultures, and foster goodwill toward Americans again is to go out in the world and be an ambassador. As in the last book, we wanted to tap into the full range of womens solo experiences. We wanted to better understand the motivations of and consequences for women who go to the effort of visiting a place far from the familiarity of home. We also were curious about what others were discovering on their solo journeys.

Once we sent out the call for submissions and spread the word, it was immediately clear how sacred womens solo journeys are to themhow many forms they take, how many reasons they set off. Their experiences and what they gain from them vary widely, but they are ultimately no less intense at different ages and times in their lives. What they set out to escape or find may not be achieved exactly as planned, but they gain new insights into themselves and othersand return to their familiar lives with renewed energy. Judging from the number of women eager to tell their stories, it was clear that we were not the only ones struck by the power of the solitary journey.

We hope you enjoy the travels revealed in these pages, and we hope they inspire you to dream of your next trip, and go your own way.

Snake Eyes of Borneo

Holly Morris

I am a voodoo doll for a sadistic nurse who is probably suffering from seasonal affective disorder, an affliction endemic to the northwestern United States and certain Scandinavian countries. Forty degrees. A cold, relentless drizzle has fallen for two months straight; the gray ceiling of the Pacific Northwest is closing in with dreaded inevitability. I am in the travel inoculation ward of Group Health Cooperative, and it is a dark February day in Seattle. As the sixth silver needle plunges into my already-throbbing arm, I think, Why am I doing this?

Questions like this usually dont arise until I am two days from anywhere, one Snickers bar left, trying to suction thick-as-syrup, muddy river water through a filter that falsely claims to remove all scents, tastes, protozoa, and bacteria. But this time, the reservations have hit me in the jab lab. Ive become a junkie, weak in the face of my drug: adventure.

Peg, the nurse, tosses her modified Dorothy Hamill haircut slightly before saying, with a tinge of admonishment, Youve come in too late to be protected from dengue fever and Japanese encephalitis. Here are the malaria pills. Theyll kill all your natural flora and fauna...

Um, fauna? I gently interject, to no response.

... so start taking acidophilus now. A small number of people get psychotic episodes from them, but I think youll be fine.

Most importantly, says Peg, unwrapping the final syringe, if something goes very wrong and things break or tear or get severely punctured, she pauses and looks me in the eye, beg for an air-evac with an IV. Dont get a transfusion.

Have fun, she concludes cheerfully, throwing the used needle into a bin that somehow hermetically seals itself, combining Andromeda Strain style with HIV reality.

I tell myself it is Pegs job to overreact. She is, after all, wearing incredibly sensible shoes.

Trips to the lab have become common since I left the deskbound world of book publishing for international documentary television. Lately, Ive been an on-the-road correspondent for a series of outdoor adventure programs. On these shoots Ive received vital lessons, such as how to lasso charging cattle, evade a posse of pregnant tiger sharks, rappel down cliffs, sweat through a sundance, run class-five rapids, and milk everything from emotional moments to smelly goats to interviews. Ive been bit on, shit on, and hit on. I asked for adventure, and I got it.