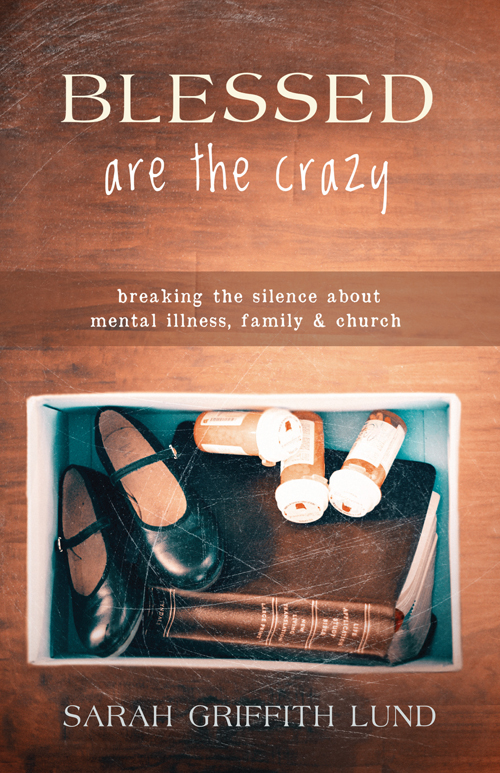

BLESSED

are the crazy

breaking the silence about

mental illness, family, and church

SARAH GRIFFITH LUND

Copyright 2014 by Sarah Griffith Lund.

All rights reserved. For permission to reuse content, please contact Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, www.copyright.com.

Bible quotations marked NRSV are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright 1989, Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Cover art and design: Shawna Everett

www.ChalicePress.com

Print: 9780827202993

EPUB: 9780827203006 EPDF: 9780827203013

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lund, Sarah Griffith, 1977

Blessed are the crazy : breaking the silence about mental illness, family, and church / by Sarah Griffith Lund.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-8272-0299-3 (pbk.)

1. Lund, Sarah Griffith, 1977- 2. Mentally illUnited StatesBiography. 3. Mentally illUnited StatesFamily relationships. 4. Mental illnessReligious aspects--Christianity. 5. Church work with the mentally illUnited States. I. Title.

RC464.L86A3 2014

616.89dc23 2014025529

Contents

A six-session guide for groups interested in discussing Blessed Are the Crazy is available on the books page on ChalicePress.com

To those who live with mental illness and their families

Definitions

cra * zy (krayzee)

1) a slang word that describes a person with a brain disease

2) a description of a situation that is out of control

cra * zy (krayzee) in the blood (blud)

1) a phrase that describes the genetic predisposition to suffering from a brain disease

Bipolar tends to run in families and appears to have a genetic link. Like depression and other serious illnesses, bipolar disorder can also negatively affect spouses, partners, family members, friends and co-workers. (From BP Magazine, summer 2014; www.bphope.com.)

2) the reason why some families are more dysfunctional than others

bi * po * lar (bi poler)

1) a brain disease that causes mood swings from the lows of depression to the highs of mania, sometimes referred to as manic depression

2) a term that describes having two poles that are extremes

Authors Note

This is my story as I remember it and re-member it. It is a work of non-fiction with a few identifying details changed to protect privacy.

I acknowledge that the language we use to talk about mental illness can be controversial because of various ways it is understood. I use the language that most closely reflects my experiences.

Foreword

It is a real privilege for me to write this foreword, especially as I know that there are others who, by virtue of their personal relationship to Sarah Griffith Lund and/or the role their writings have played in her own healing process, are far more qualified than I to write it.

As you will discover, Sarah has been deeply acquainted with mental illness since her early childhood. One might say that mental illness has been her constant companion, a companion one surely does not seek out or extend a welcoming hand. As she relates in her testimony, her father was mentally ill, her brother is mentally ill, her cousin was executed for a crime that revealed his own mental illness, and she herself has experienced spiritual visions that others might consider signs of mental illness.

And yet, hers is an inspiring testimony that reveals the healing powers of the very act of testifying to the brokenness that one has both witnessed and experienced vicariously. As she points out, The power of our testimonies is the power to work through, heal, and eventually transform our suffering. Telling the stories about my crazy father, bipolar brother, executed cousin, and my own spiritual visions makes room for light and air, the things of Gods Spirit, to enter in. Not to have testified as she has done here would have been the real tragedy, more tragic than the mental illnesses recounted in these pages. For, as she also notes, Keeping these stories as secrets buried deep down in my soul gives them power to hold me captive, isolated by my own fear, shame, and pain: fear that I too, will be labeled crazy and, therefore, unlovable: shame that I am not good enough to be loved; pain because this suffering makes me feel alone in the world.

I learned from students that the first step in the healing process is often the ability to overcome the need of our idealized self to critiqueeven condemnour shameful self and to recognize, instead, that God identifies with our shameful self.

Given these experiences with students, I wholeheartedly agree with Sarahs view, presented so eloquently here, that the fundamental key to the process of healing is to testify to the role that mental illness has played in our lives and thereby free ourselves from our prisons of fear, shame, and pain, and open the doors to liberated lives based on hope, healing, and love.

Sarah also perceives that we live in a new age as far as mental illness is concerned. She writes, As a society we are just now beginning to tell our stories in public about mental illness, and that getting it out in the opentalking about it on the radio, television, in books, on blogs, in schools, and in churchesis progress. For too long the churches have conspired against the telling of these stories. Traditionally, they have done very little to support the mentally ill and their families. However, this is not the time to condemn, but rather to seize the initiative and to encourage the churchs leaders to take fuller advantage of the trust that laity invest in them and of the prerogative that comes with being pastors. As I wrote in another foreword, this time for a book by Stewart D. Govig, whose son was diagnosed with schizophrenia in his early twenties:

Pastors may begin with a ministry of simple presence. From this basis, they may proceed to monitor their ownand othersstigmatizing language. They may educate and do so, rather surprisingly, through curricula that is not trendy but traditional, beginning with biblical stories of Jesus own affinity with the mentally ill. They may also become advocates, as Govig himself has become, discovering that the support of a local pastor makes a potent difference among the afflicted families and the wider community. Not least of all, they may become the receivers, as have grieving family members, of the witness the mentally ill themselves have to give to the strong who are lost in their own illusions of security. Did not Jesus preach about the man who gathered his grain into barns and assured himself that he had ample goods laid up for many years, only to discover that the things he had prepared were suddenly swept away, in the twinkling of an eye? The mentally ill testify to the folly of such complacency.

For me, the most inspiring story that Sarah tells here is her account of her relationship with her brother Scott, who, like Govigs son John, began to exhibit psychotic behaviors in his senior year in high school. The power of her testimony here is, to me, the fact that her roles as pastor and sibling are interactive and mutually supportive. This is also the case with Govig and his son John. But, as I have noted, pastors are also