Introduction to Music Theory

Collection edited by: Catherine Schmidt-Jones

Content authors: Catherine Schmidt-Jones and Russell Jones

Online:

This selection and arrangement of content as a collection is copyrighted by Catherine Schmidt-Jones .

It is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/1.0

Collection structure revised: 2005/03/14

For copyright and attribution information for the modules contained in this collection, see the "" section at the end of the collection.

Chapter 1. Pitch and Interval

1.1. Octaves and the Major-Minor Tonal System

Note

Are you really free to use this online resource? Join the discussion at Opening Measures.

Where Octaves Come From

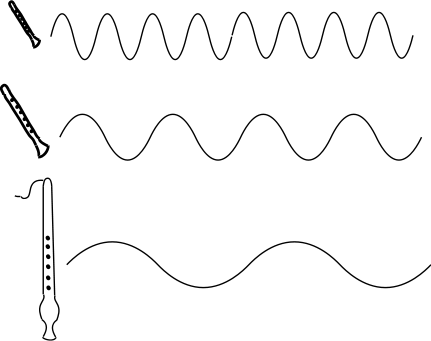

Musical notes, like all sounds, are made of sound waves. The sound waves that make musical notes are very evenly-spaced waves, and the qualities of these regular waves - for example how big they are or how far apart they are - affect the sound of the note. A note can be high or low, depending on how often (how frequently) one of its waves arrives at your ear. When scientists and engineers talk about how high or low a sound is, they talk about its frequency. The higher the frequency of a note, the higher it sounds. They can measure the frequency of notes, and like most measurements, these will be numbers, like "440 vibrations per second."

Figure 1.1. High and Low Frequencies

A sound that has a shorter wavelength has a higher frequency and a higher pitch.

But people have been making music and talking about music since long before we knew that sounds were waves with frequencies. So when musicians talk about how high or low a note sounds, they usually don't talk about frequency; they talk about the note's pitch. And instead of numbers, they give the notes names, like "C". (For example, musicians call the note with frequency "440 vibrations per second" an "A".)

But to see where octaves come from, let's talk about frequencies a little more. Imagine a few men are singing a song together. Nobody is singing harmony; they are all singing the same pitch - the same frequency - for each note.

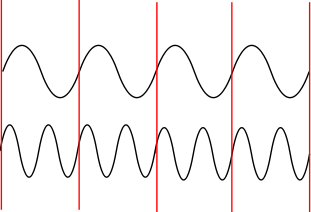

Now some women join in the song. They can't sing where the men are singing; that's too low for their voices. Instead they sing notes that are exactly double the frequency that the men are singing. That means their note has exactly two waves for each one wave that the men's note has. These two frequencies fit so well together that it sounds like the women are singing the same notes as the men, in the same . They are just singing them one octave higher. Any note that is twice the frequency of another note is one octave higher.

Notes that are one octave apart are so closely related to each other that musicians give them the same name. A note that is an octave higher or lower than a note named "C natural" will also be named "C natural". A note that is one (or more) octaves higher or lower than an "F sharp" will also be an "F sharp". (For more discussion of how notes are related because of their frequencies, see The Harmonic Series, Standing Waves and Musical Instruments, and Standing Waves and Wind Instruments.)

Figure 1.2. Octave Frequencies

When two notes are one octave apart, one has a frequency exactly two times higher than the other - it has twice as many waves. These waves fit together so well, in the instrument, and in the air, and in your ears, that they sound almost like different versions of the same note.

![Michael Miller - Idiots Guides: Music Theory, Third Edition [Book]](/uploads/posts/book/161692/thumbs/michael-miller-idiot-s-guides-music-theory.jpg)