Published in 2011 by The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Copyright 2011 by The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

First Edition

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Cook, Colleen Ryckert.

Frequently asked questions about cancer decisions for you and your family / Colleen Ryckert Cook.1st ed.

p. cm.(FAQ: teen life)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4488-1326-1 (libr. bdg.)

1. CancerPopular works. I. Title.

RC263.C6486 2011

616.99'4dc22

2010018501

Manufactured in the United States of America

CPSIA Compliance Information: Batch #W11YA: For further information, contact Rosen Publishing, New York, New York, at 1-800-237-9932.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

I HAVE CANCER. WHAT HAPPENS NOW?

In the next months, you and your family will focus on learning all you can about your cancer. Your existence will seem to revolve around oncologist appointments. You'll get so used to having blood drawn that you won't even flinch at needles. In no time, you'll rattle off four- and five-syllable medical terms like a pro. You'll probably memorize the names of entire nursing staffs.

It's difficult, scary, and lonely. You probably feel like you're the only teen in the world dealing with cancer. The truth is lots of other teens and even younger children are going through the same thing. The National Cancer Institute's Surveillance and Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program gathers cancer statistics in America. According to SEER's most recent estimates, more than forty-seven thousand children and teens live with cancer each year. Many have dealt with it for five years or more. This year alone, about eighteen thousand will hear the words "you have cancer for the first time.

Remember how you felt when you heard you had cancer? You're probably still processing what this means. It takes time. Some teens are scared at first. Others are convinced the doctors were wrong. Some want to hide or don't want friends to know. And some feel determined to beat cancer fast.

Nearly every single teen with cancer will tell you the same thing. During long months and even years of treatment, they ride a roller coaster of emotions. Depending on the day and sometimes even the hour, they feel frustrated, joyful, dismal, goofy, angry, hopeful, and often, believe it or not, bored.

Why Did I Get Cancer?

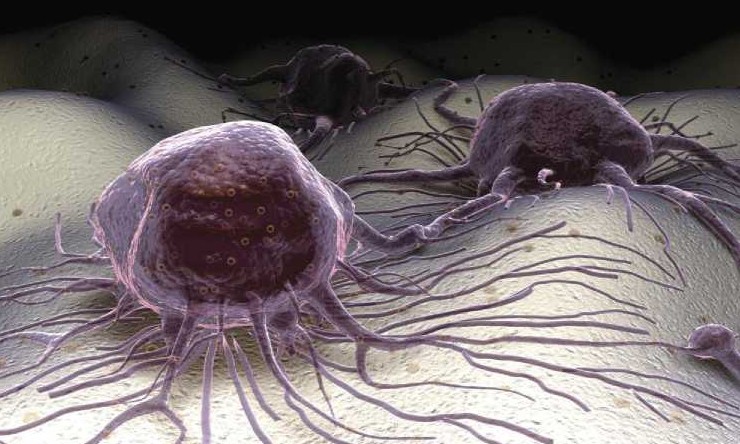

The simple response: the deoxyribonucleic acid, or DNA, changed in some of your cells, which allowed them to grow out of control. Those cells no longer function properly.

Our bodies have tumor-suppressor genes. These genes slow down cell division and help repair DNA errors. They also tell cells to die off to make room for new cells. Different genes, called proto-oncogenes, control cell function and division. Mutated proto-oncogenes are called oncogenes. Oncology, or the study of cancer, comes from this word. If oncogenes grow out of control or tumor-suppressor genes stop working, the result is cancer.

We know prolonged exposure to certain things can cause cancer. We call them carcinogens. Common carcinogens include asbestos, cigarettes and second-hand smoke, coal tar, hepatitis C, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), radon, and ultraviolet rays and X-rays.

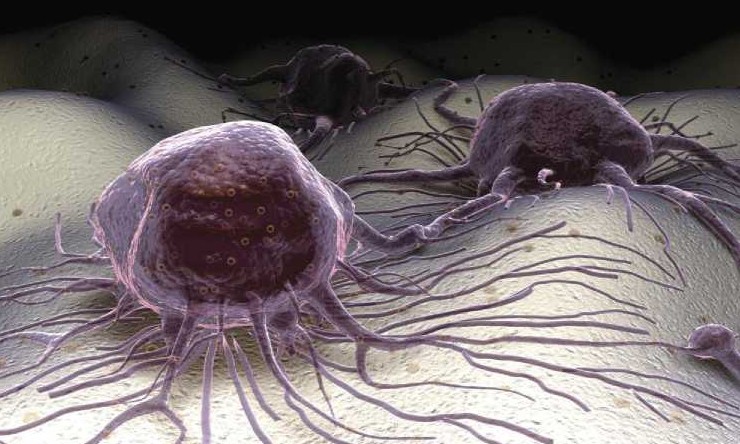

Changes in DNA cause some cells to mutate. Cancer happens when mutations grow out of control. These faulty cells latch onto healthy cell surfaces and affect function.

Your cells might have a predisposition, passed down in your family, to mutate. Many mutations develop in embryos or show up shortly after birth. Some pop up decades later to catch everyone by surprise.

For whatever reason, something went wrong inside your cells. Remember those cellular mitosis lessons from science class? Each time a mutated cell divides to create a new cell, the mutation repeats. Over time, a mass of altered cells forms.

Sometimes these masses, or tumors, are benign. They're in the way but harmless. Other tumors, like what you're dealing with, are malignant. They make an impact on the cells around them. The body can't function the way it should.

What Kinds of Cancers Do Teens and Children Develop?

"Cancer" is a blanket term for hundreds of diseases. Leukemia, or cancer of the white blood cells, is the most common malignancy that affects children. According to the National Cancer Institute, leukemia accounts for about thirty-three out of every one hundred childhood cancer diagnoses. Brain tumors, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, soft tissue cancers, and Hodgkin's lymphoma are the other most frequently occurring cancers in people under age twenty.

For young people between the ages of seven and sixteen, however, bone and soft tissue cancers (called sarcomas) are more common. This is because the body goes through growth spurts during those years: bone and soft tissue cells multiply quickly during puberty as an adolescent's body matures.

Your doctors will provide information for your specific cancer, but here is some general information from the National Cancer Institute and SEER about common cancers in older children and teens.

Leukemia

Leukemia is a blood cancer that causes bone and joint pain, bleeding, weight loss, fatigue, and other symptoms. The most common type is acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), which accounts for about 80 percent of childhood leukemias. Acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) accounts for about 20 percent of childhood leukemias, although a few other rare forms also exist. Although childhood leukemia sounds really scary, the overall five-year survival rates are actually now between 80 percent and 85 percent. This means children diagnosed with leukemia were treated successfully (in remission) and are alive five years later.

Brain Tumors

Brain tumors are the next most common cancer of childhood. These tumors can appear anywhere in the brain or spine, but most often occur in the brain stem (where the spinal cord joins the back of the brain) or cerebellum (an area of the back of the brain that coordinates movement). Symptoms depend on where the tumor pops up. They can include trouble with speaking, vomiting, headaches, vision problems, seizures, coordination problems, numbness, weakness, and personality changes.

There are many different types of brain tumors, and they are named for the type of cell from which they arose and sometimes by their location. About half of all childhood brain tumors are called astrocytomas, which can be low grade (benign) or high grade (malignant). These tumors develop from astrocytes, which are supporting cells (glia) within the brain and spinal cord. These tumors tend to look spindly and can spread easily into healthy tissue. This can make them hard to remove surgically. Other common brain tumors are called primitive neuroectodermal tumors (PNETs) because they start in primitive (immature) nerve cells. PNETs account for about 20 percent of childhood brain tumors. Medulloblastoma is a kind of PNET. There are also dozens of other less common central nervous system tumors.

Many brain tumors in children are called indolent, which means the tumors grow slowly. Other tumors grow more quickly, such as anaplastic astrocytomas and glioblastomas multiforme (the most aggressive type of astrocytoma). Depending on the type and location, brain tumors are treated with surgery, radiation, and/or chemotherapy.