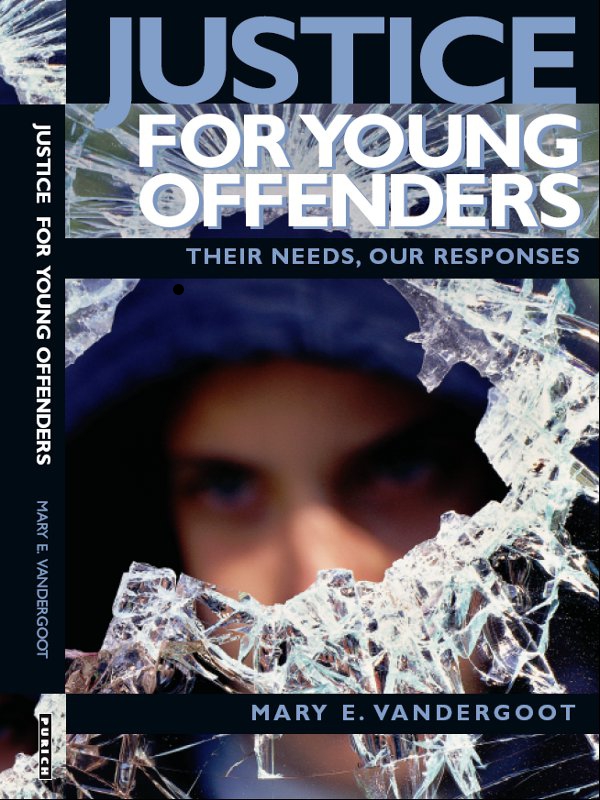

Justice for Young Offenders

THEIR NEEDS, OUR RESPONSES

Mary E. Vandergoot

Copyright 2006 Mary E. Vandergoot

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review, or in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a license from ACCESS (Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency) in Toronto. All inquiries and orders regarding this publication should be addressed to:

Purich Publishing Ltd.

Box 23032, Market Mall Post Office

Saskatoon, SK Canada S7J 5H3

Phone: (306) 373-5311 Fax: (306) 373-5315

Email: purich@sasktel.net

Website: www.purichpublishing.com

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Vandergoot, Mary Ellen, 1956

Justice for young offenders : their needs, our responses / Mary E. Vandergoot.

Includes index.

ISBN 1-895830-27-3

1. Juvenile justice, Administration of Canada. 2. Juvenile delinquents Canada Social conditions. 3. Juvenile delinquents Canada Psychology. I.

Title.

HV9108.V35 2006 364.360971 C2006-903432-X

Cover design by Duncan Campbell.

Cover photo by Andrew Douglas/Masterfile.

Editing, design, and layout by Donald Ward.

Index by Ursula Acton.

Printed in Canada by Houghton Boston Printers and Lithographers.

Publishers Note: Most legal case citations are to CanLII (www.canlii.org), a not-for-profit organization initiated by the Federation of Law Societies of Canada, which provides free access to legal resources. All case studies are composites, and any similarity to actual persons is accidental.

URLs for websites contained in this book are accurate to the time of writing, to the best of the authors knowledge.

Purich Publishing gratefully acknowledges the assistance of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund (CBF), and the Creative Industry Growth and Sustainability Program made possible through funding provided to the Saskatchewan Arts Board by the Government of Saskatchewan through the Ministry of Tourism, Parks, Culture and Sport for its publishing program.

I would like to dedicate this book to R. and S., two young people I never met, but whose names were in my appointment book. They never arrived for their appointments with me. I dedicate this book to them in recognition of their pain and loneliness, which each day reminds me of the youth who fall between the cracks and those for whom we never knew how or when to intervene. The tragedy of their untimely deaths continues to shake my spirit and inspired the writing of this book.

CONTENTS

I would not have been able to complete this project without the continual support, friendship, and love of my husband, Robin Hawrysh. He read many initial drafts, offered guidance, and listened to me for many hours while I grappled with the project. I could not have completed the book without his patience and confidence in me.

I also thank my family, especially my children and my mother, who encouraged me along the way. I also thank my friends and colleagues who encouraged me throughout this project.

I am very grateful that the Young Offender Team, Child and Youth Program, Mental Health and Addiction Services, granted me a temporary reduction in my hours so I could work part-time while I wrote the book. I am also indebted to the many young people, parents, and professionals with whom I was fortunate to work during my time with the Young Offender Team in Saskatoon.

I thank Karen Bolstad and Don Purich of Purich Publishing, of Saskatoon, who saw the value of publishing a book of this nature. Their vision, support, and guidance throughout the writing and editing stages of the book helped me articulate my ideas and complete the project to the best of my abilities. I also thank editor Donald Ward for his editorial assistance with the completion of this book. I am also grateful to Karen Bolstad for her skill in ensuring the accuracy of the text during the final stage of editing.

There are many individuals who supported this project and assisted me with refining the text. I would like to acknowledge the helpful feedback on earlier drafts of selected chapters that I received from my family, friends, and colleagues, including: Chris Johnstone, Dr. Debby Boyes, Dr. Patricia Blakley, Judge Sheila Whelan, Kearney Healy, Rhonda Woolsey, Bryan Barker, and Elinor Keter. I am also indebted to Russell Smandych, Department of Sociology, University of Manitoba, whose constructive and helpful comments during an earlier stage of the project were very valuable.

The views expressed in this book are entirely my own and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of the Saskatoon Health Region, where I have been an employee since 1998. In referencing a number of publications, I have attempted to represent or interpret the views of the authors in a manner that is accurate and reasonable; however, should there be errors in fact or interpretation, neither my reviewers nor editor should be held responsible; they are entirely of my own, albeit, non-intentional, making.

The case examples used in this book are constructed in such a way that the identity of any person or family cannot be made. Significant facts about their identities have been altered to ensure that their true identities remain hidden. I apologize for any unintentional harm that may be caused by experiences of dj vu the reader may encounter during the reading of this book. I have, to the best of my ability, obscured the details and identity of all persons and their situations. Nonetheless, some of the experiences, or the descriptions of characteristics of persons, may be similar to persons the reader knows. This is because many of the experiences described in this book may ring true to personal experiences, for they are not uncommon in the lives of Canadian families. However, I would like to assure the reader that any similarities between the persons and situations described in this book and the personal experiences of the reader are entirely coincidental.

INTRODUCTION

Toward a Disability Paradigm

Canadian society has a history of using the criminal justice system to address the social and mental health issues of youth. The assumptions behind this practice range from the well-meaning to the punitive. One line of reasoning is that youthful offending needs to be nipped in the bud, so young people must be involved with the justice system at an early age to prevent them from becoming hardened criminals. Alternatively, many children are in need of protection and should be involved with the justice system to be kept safe. Finally, some people reason that many youth are in need of mental health treatment, and involvement with the justice system is one way of ensuring that they get it.

These assumptions are based on the child welfare model of youth justice, or the notion of parens patriae the state as parent. In this model, the youth justice system functions as a surrogate parent to wayward youth especially those who are disconnected from family and other supports. The consequences of relying on criminal sanctioning to respond to the social and mental health issues of youth has led to a new social problem in Canada the disproportionate representation of youth with intellectual disabilities and other mental health issues who are in the justice system. A large number have histories of victimization and neglect. Many have learning problems, or may even be illiterate. The most common mental disorders seen in young offenders include disruptive behaviour, mood and anxiety disorders, substance abuse and dependence, and cognitive and behavioural disorders related to fetal alcohol spectrum disorders and intellectual and learning disabilities.

Next page