Contents

Guide

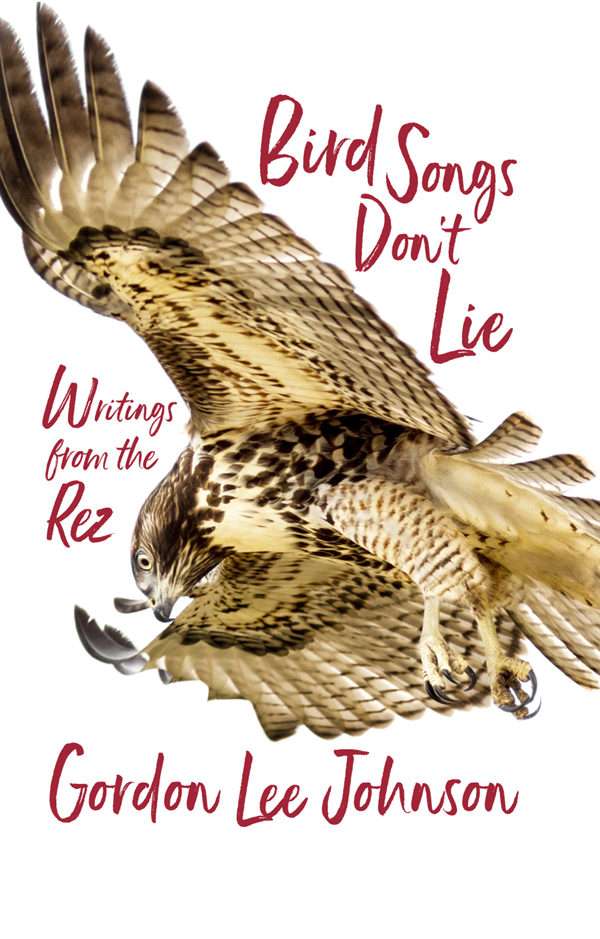

Copyright 2018 by Gordon Lee Johnson

The columns in this book originally appeared in the Press-Enterprise, sometimes in slightly different form. Indian Love, One Hundred White Women, and A Rez Take on Mission Food originally appeared in News from Native California.

All rights reserved. No portion of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from Heyday.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

Cover Photo: Patricia Ware

Cover and Interior Design/Typesetting: Ashley Ingram

Orders, inquiries, and correspondence should be addressed to: Heyday

P.O. Box 9145, Berkeley, CA 94709

(510) 549-3564

www.heydaybooks.com

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To my childrenTyra, Missy, Brandon, and Jaredin whose eyes I see myself a better man.

A shout-out to Matthew Goodman, a Vermont College mentor, who with patience and skill unlocked secrets to the craft of fiction. And to N. Scott Momaday, who made me want to write.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

Although born at UCLA Hospital and raised for the first five years of my life in Los Angeles, I have lived most of my life far away from California. When I come home for a visit I see it with different eyes from those who have never left. Everything is new to me, and, at the same time, I remember and know every detail.

There should be a word for that, the way dj vu means you feel like something has already happened even though you know it hasnt. Dj vu is not it, not what I feel when I step out onto California land. This is, perhaps, more of a bone and blood memory: the air, minerals, water, scents, pollen, light, angle of the sun and stars that my body remembers, that some deep part of my brain remembers.

Usually this is triggered simply by being in California: feeling the thunder of surf on a flat sweep of beach, stepping over the rampant roots of huge fig trees bursting through slabs of sidewalk, or smelling eucalyptus on the evening air, running my hand along the ancient spears of agave or sitting beneath the shameless purple blossoms of jacaranda.

A few years ago in Westwood, I stepped on board a busand suddenly stepped back into my four-year-old body, going up those black steps, my hand in my mothers hand, sitting next to the window looking out at hot sidewalks and palm trees along the way. I had never remembered taking a bus with my mother in Los Angeles, yet now I felt as if Id never been without that memory. It was as much a part of me as the color of my hair.

Science tells us that our bodies carry oxygen atoms from the water we drank as children; these isotopes are stored in our teeth. (Most teeth are formed either before birth or during childhood.) Therefore, analysis of our teeth tells the story of where we are fromwe carry traces of our first home inside us, wherever we go. Ive often wondered if this is the cause of the almost magnetic attraction I feel toward the landscapes of Southern Californiathe pull of my origins toward home. My experiences in California as a middle-aged woman are constantly doubled with memories of being a child theresensory memories, emotional memories that shadow my every move. In some ways, it feels like walking simultaneously on two timelines; my two bodiesone three or four years old, one fifty-somethingconnected suddenly by the geographic location and my history with it.

Reading Gordon Lee Johnsons Bird Songs Dont Lie does the same thing to me. The stories within this collectionboth memoir and fictionpull on all my senses, spiral me through time: flashes of red chili sauce, cast-iron pans, fiesta, abalone shell, sage, old cars that wont die or die too soon, the familiar weight of adobe, the voices of aunties, the omnipresent Church, priest, death, hope. Gordons rich memories intertwine with a world I remember, a world I have come back to time and time again, apprenticing myself to my elders, my relatives, and the land, in an effort to earn my place.

And yet, because Gordon has lived in California most of his life, his stories also fill in the empty spaces where my own memories are absent. His characters speak in honest, sometimes pain-filled voices about the complexities of contemporary life on a California rez, of living in the shadow of missionization, colonization, genocide, and all the ways those histories haunt us.

Perhaps what I appreciate most about the personal essays is the thoughtfulness of Gordons observations about the ways tribal culture has endured, adapted, grown around obstacles, and sometimes faded, only to sprout up in some unexpected place.

Luiseo Initiation is one such moment: I was born too late for an initiation ceremony, Gordon writes a little sadly, outlining the meticulous process that once involved hours, if not days, of preparation, deprivation, and the use of certain plants that shall not be named. He notes that at the heart of the initiation ceremony was the lecture on how to conduct oneself in the right way.

Without missing a beat, he recaps the lecture as hes read about it in notes by a self-taught ethnologist from the 1890s, puts the advice into a language and context that makes sense for someone caught up in the complications of post-missionized reality. Reviewing these teachings, Gordon writes, I take another sip of Negra Modelo, and Im heartened. I love this line, the deceptive simplicity it implies.

I know darn well that self-taught ethnologist may have fudged a little in his word-for-word record of an elders lecture to young Indians undergoing the coming-of-age ceremony. Gordon knows it, too. I wouldnt be a bit surprised if he did a little revision of his own.

Thats what makes this essay, like his others, ring with so much truth.

There are bird-song rattles made out of ancient cottonwood, smoothed by an honored grandfathers knife, worn to fit his handand then there are bird-song rattles thrown together in the heat of the moment around a campfire, just an old beer can full of pebbles, a stick, and some duct tape.

The secret that good bird singers all know is that, while an heirloom instrument is nice, its the song that matters. Its the song that cant, ever, tell a lie.

Nimasianexelpasaleki, Gordon. Your songs make my heart happy. May they go out into the world and find the ears that need to hear them, find homes in hungry hearts, and continue this work of rebuilding the California Indian world.

kolo,

Deborah A. Miranda

Columns and Essays

LOSS OF A FRIEND BRINGS MEMORIES

Im dialing the way-back machine to circa 1975.

On Sundays Ed Arviso, Ronnie Powvall, and I would be hungover. We lived in a small house on Grape Street in Escondido. In the fridge there would be ice water in a brown ceramic jug with a cork stopper, the kind of jug a hillbilly might drink corn liquor from.

In the fridge, there would be a length of bologna, the kind encased in a red plastic wrapper, bought from Poor Ol Rubes, a now defunct grocery store.

There would be a block of commodity cheese that Ronnie had gotten from his sister, Debbie.