THE TAUBER INSTITUTE SERIES

FOR THE STUDY OF EUROPEAN JEWRY

Jehuda Reinharz, General Editor

ChaeRan Y. Freeze, Associate Editor

Sylvia Fuks Fried, Associate Editor

Eugene R. Sheppard, Associate Editor

The Tauber Institute Series is dedicated to publishing compelling and innovative approaches to the study of modern European Jewish history, thought, culture, and society. The series features scholarly works related to the Enlightenment, modern Judaism and the struggle for emancipation, the rise of nationalism and the spread of antisemitism, the Holocaust and its aftermath, as well as the contemporary Jewish experience. The series is published under the auspices of the Tauber Institute for the Study of European Jewryestablished by a gift to Brandeis University from Dr. Laszlo N. Tauberand is supported, in part, by the Tauber Foundation and the Valya and Robert Shapiro Endowment.

For the complete list of books that are available in this series, please see www.brandeis.edu/tauber

ChaeRan Y. Freeze

A Jewish Woman of Distinction: The Life and Diaries of Zinaida Poliakova

Chava Turniansky

Glikl: Memoirs 16911719

Dan Rabinowitz

The Lost Library: The Legacy of Vilnas Strashun Library in the Aftermath of the Holocaust

Jehuda Reinharz and Yaacov Shavit

The Road to September 1939: Polish Jews, Zionists, and the Yishuv on the Eve of World War II

Adi Gordon

Toward Nationalisms End: An Intellectual Biography of Hans Kohn

Noam Zadoff

Gershom Scholem: From Berlin to Jerusalem and Back

*Monika Schwarz-Friesel and Jehuda Reinharz

Inside the Antisemitic Mind: The Language of Jew-Hatred in Contemporary Germany

Elana Shapira

Style and Seduction: Jewish Patrons, Architecture, and Design in Fin de Sicle Vienna

ChaeRan Y. Freeze, Sylvia Fuks Fried, and Eugene R. Sheppard, editors

The Individual in History: Essays in Honor of Jehuda Reinharz

Immanuel Etkes

Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liady: The Origins of Chabad Hasidism

HBI SERIES ON JEWISH WOMEN

Sylvia Barack Fishman, General Editor

Lisa Fishbayn Joffe, Associate Editor

The HBI Series on Jewish Women, created by the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute, publishes a wide range of books by and about Jewish women in diverse contexts and time periods. Of interest to scholars and the educated public, the HBI Series on Jewish Women fills major gaps in Jewish Studies and in Women and Gender Studies as well as their intersection.

The HBI Series on Jewish Women is supported by a generous gift from Dr. Laura S. Schor.

For the complete list of books that are available in this series, please see www.brandeis.edu/hbi

ChaeRan Y. Freeze

A Jewish Woman of Distinction: The Life and Diaries of Zinaida Poliakova

Chava Turniansky

Glikl: Memoirs 16911719

Joy Ladin

The Soul of the Stranger: Reading God and Torah from a Transgender Perspective

Joanna Beata Michlic, editor

Jewish Families in Europe, 1939Present: History, Representation, and Memory

Sarah M. Ross

A Season of Singing: Creating Feminist Jewish Music in the United States

Margalit Shilo

Girls of Liberty: The Struggle for Suffrage in Mandatory Palestine

Sylvia Barack Fishman, editor

Love, Marriage, and Jewish Families: Paradoxes of a Social Revolution

Cynthia Kaplan Shamash

The Strangers We Became: Lessons in Exile from One of Iraqs Last Jews

Marcia Falk

The Days Between: Blessings, Poems, and Directions of the Heart for the Jewish High Holiday Season

Inbar Raveh

Feminist Rereadings of Rabbinic Literature

Laura Silver

The Book of Knish: In Search of the Jewish Soul Food

Sharon R. Siegel

A Jewish Ceremony for Newborn Girls: The Torahs Covenant Affirmed

*A Sarnat Library Book

PREFACE

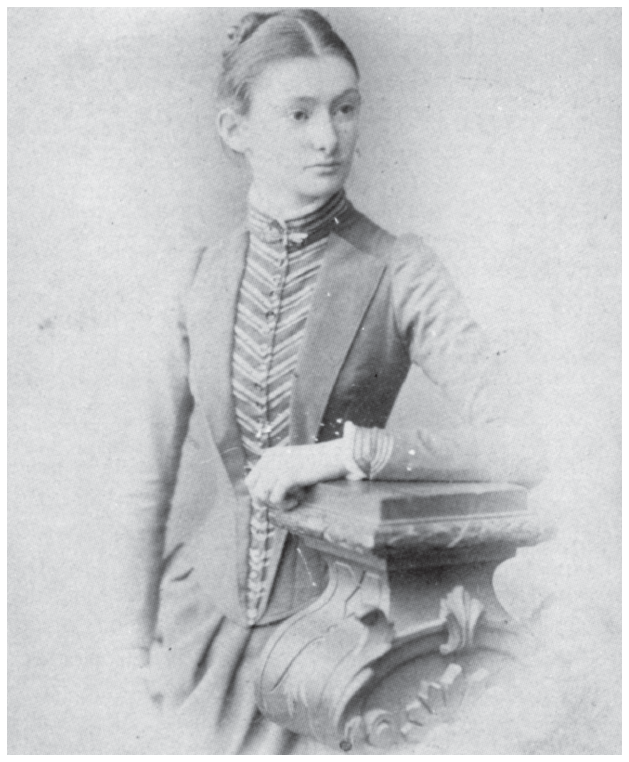

The discovery of a Jewish womans diaries in Russia is exceedingly unusualnot to mention the fact that they span nearly three-quarters of a century and several countries. Zinaida Lazarevna Poliakova (18631952), who hailed from one of the wealthiest Jewish banking families in the Russian Empire but lived in France and England after her marriage in 1891, would have been bemused to learn that her diaries found their way back to her beloved Russia in the post-Soviet era. The diaries first went to the actress Vera Poliakoff (the granddaughter of Zinaidas cousin Lazar Iakovlevich), then to the Russian-born electronics engineer Alexander Poliakoff, and last to Sir Martyn Poliakoff, a distinguished British chemist. He then donated them to the Manuscript Division of the Russian State Library in Moscow, where they are now preserved. Parts of the diaries were published in 1995 along with the memoirs of Alexander Poliakoff.

Zinaida Poliakova was twelve years old when she began writing her diaries for nothing to do at the family dacha in Sokolniki (just outside of Moscow). Childish boredom gradually gave way to a serious resolve to record the details of her life so that I will enjoy reading it in a few years. As she matured, Zinaida poured her emotions and impressions into her diaries, which became a space where she could express her rage, hurt, scorn, or amusement without fear of reprisals. On some days (especially when she lived in France), she simply scribbled trivial notes about the weather or her bad headaches. After all, Zinaida wrote the diaries for herself, never imagining that an audience outside her immediate family or friends might read them.

Her ten surviving diaries represent a treasure trove for historians and are unique in several respects. First, although Jewish women wrote diaries in Imperial Russia, few have survived the ravages of war, migrations, or purges by heirs or zealous cleaners who did not understand the value of the notebooks. In fact, the only other known diaries of a Jewish woman from this period (although others certainly survived in private archives or family documents) are those of the writer Rashel Mironovna Khin (18611928), who described her social, intellectual, and cultural life in Moscow from 1891 to 1917. She converted to Christianity to escape an unhappy marriage and married a fellow convert, Osip Goldovsky, a Moscow lawyer. Like Zinaida, she was immersed in Russian culture but socialized more with the leading intellectual and literary figures of her day rather than with aristocrats and bureaucrats.

Second, the remarkable time span of Zinaidas diaries affords a rare glimpse into the entire trajectory of one womans life. She wrote her first entry on 13 August 1875 as a young girl and her final entry sometime in late 1949, when she was eighty-six years old. She lived through the period when aristocratic society in Moscow was at its apogee, under the general-governorship of Prince Vladimir Dolgorukov; experienced the fall of the tsarist regime and the arrest of her family members by the Bolshevik regime (albeit from afar in Paris); survived both catastrophic world wars and the loss of her closest relatives and friends during the Holocaust; and managed to live through the difficult postwar years with the help of her husbands relatives in England. It is possible to trace how her aristocratic upbringing influenced her life from childhood to old age, as well as the impact of life-changing events like the Holocaust on her attitudes toward religion and family.