Contents

Page List

Guide

Cover

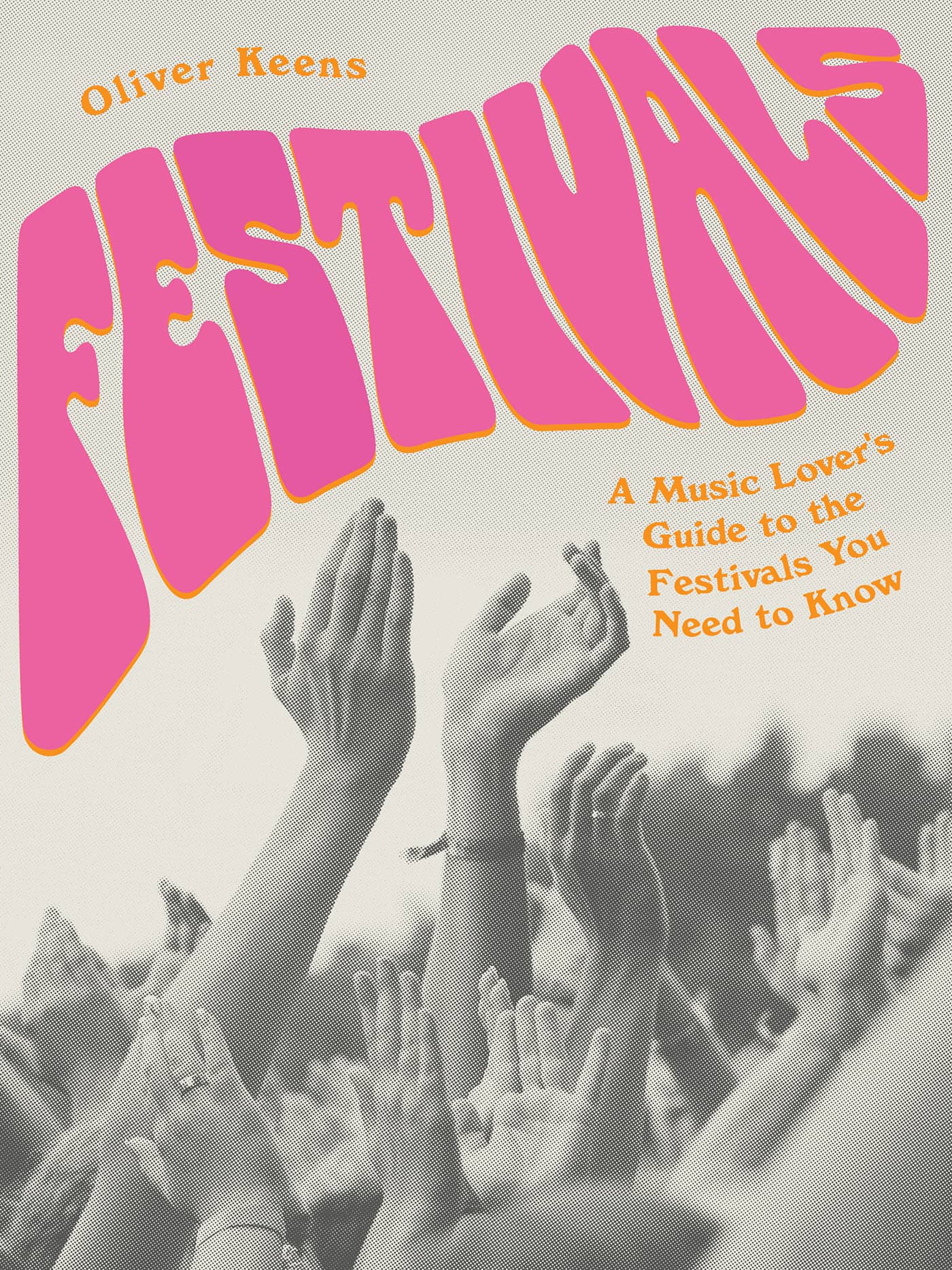

Oliver Keens

FESTIVALS

A Music Lover's Guide

to the Festivals You

Need to Know

Contents

Introduction

For some people I know, festivals begin with a certain smell a mix of grass, generators and portable loos. For others, its the feeling of finally getting out of a vehicle after hours and taking that first, calibrating step onto the bumpy, squelchy terrain that will be home for the next few days. Maybe it begins with opening a can or five on a train, or by ritualistically planning your entire band schedule for the whole weekend. Or perhaps it starts weeks before, when someone starts a WhatsApp group. Festivals begin in lots of different ways, but if theyre good festivals, they should all end the same way: with everyone leaving a slightly different person from when they arrived.

Great festivals are life-changing experiences. Over the course of this book, well see how superficially at least the experience of a music festival has changed too. Where Woodstocks attendees were grateful to sustain themselves on small cups of granola, today you can be catered for by Michelin-starred chefs at Belgiums Tomorrowland, or visit a fully stocked, purpose-built Lidl supermarket in the campsite of Germanys Rock am Ring. While the first festival held at Michael Eavis Glastonbury farm in 1970 cost 1 (including free milk), the price of attendance in 2019 was 248 (no milk included).

Observers of a certain age are quick to point to the modern cost of festivals as an example of their decline. Festivals are not radical, they say. Theyre not about peace and love, theyre just about business.

Festivals certainly are businesses today, but never forget that they are businesses that still require passionate, madcap, selfless mavericks to make happen, weekend-after-weekend. As this book shows, it has always been thus. Festivals only work when someone is crazy enough to endure the endless egos of artists and their managers, to choose to be responsible for the safety of thousands of drunk or high punters as they interact with hundreds of temporary structures and stages, held up on a wing and a prayer. Theyre folk whose livelihoods sit at the mercy of the fickle gods of weather. This book is in part a tribute to the strange, brave, borderline insane people who make festivals happen, all around the world.

What makes festivals so great? Well, above all else theyre captive experiences. Theyre carnivals you live in, with little chance to escape. Theyre gigs that go on for days and days. Theyre immersive in a way that no other strand of arts and culture can rival, and as a result, they are the perfect Petri dish for great memories. Long may festivals continue to create a never-ending supply of memories.

Respect Festival, London, 2001

Sunset at Camp Bestival, Dorset, UK

Montreux Jazz Festival

Theres a brilliant online project called Things That Are Called Jazz That Are Not Jazz. Its a directory of things that have the word jazz in their name, but have nothing to do with jazz music. For example, you can eat a Jazz apple, drive a Honda Jazz, or spray yourself with an Eau de Toilette called Jazz. We mention it, because the great Montreal Jazz Festival has become a borderline entry to the list.

MJF today is not a jazz festival. Unless you count ZZ Top, Nick Cave, Tyler, The Creator or Alanis Morissette as jazz (the last is definitely not jazz, not even ironically). But while the festival which descends annually on the Swiss town bordering Lake Geneva has slowly diversified, to the point where Grimes or A$AP Rocky have played, it of course has jazz at its heart. Status Quo may have headlined twice, but any festival where Herbie Hancock has performed twenty-seven times (a Montreux record) has to score highly on the jazz-o-meter.

Its one of the worlds longest-running festivals, starting back in 1967, when greats such as Nina Simone and Ella Fitzgerald gathered to play the Montreux Casino. This first home burned down in dramatic fashion during the 1971 festival, when a fan (unbelievably by modern standards) fired a flare gun at an impossibly flammable rattan ceiling. This event was immortalised by rock band Deep Purple in their chuggy anthem Smoke On The Water, which so flattered the people of Montreux for being indelibly linked to rock history that there even used to be a waterside sculpture in the songs honour.