While the Gods Were Sleeping

A Journey Through Love and Rebellion in Nepal

Copyright 2014 Elizabeth Enslin

SEAL PRESS

A Member of the Perseus Books Group

1700 Fourth Street

Berkeley, California 94710

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form without written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who may quote brief excerpts in connection with a review.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Enslin, Elizabeth,

While the gods were sleeping : a journey through love and rebellion in Nepal / by Elizabeth Enslin.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-58005-543-7

1. Enslin, Elizabeth, 1960- 2. Nepal--History--1951---Biography. 3. Nepal--Politics and government--1990- 4. Enslin, Elizabeth, 1960---Marriage. 5. Americans--Nepal--Biography. 6. Women anthropologists--United States--Biography. 7. Intercountry marriage--Case studies. 8. Brahmans--Nepal--Chitawan (District)--Biography. 9. Women--Nepal--Chitawan (District)--Biography. 10. Women--Nepal--Chitawan (District)--Social conditions--20th century. I. Title.

DS495.592.E56A3 2014

954.96--dc23

[B]

201400924210 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Cover design and Interior design by Gopa & Ted2, Inc.

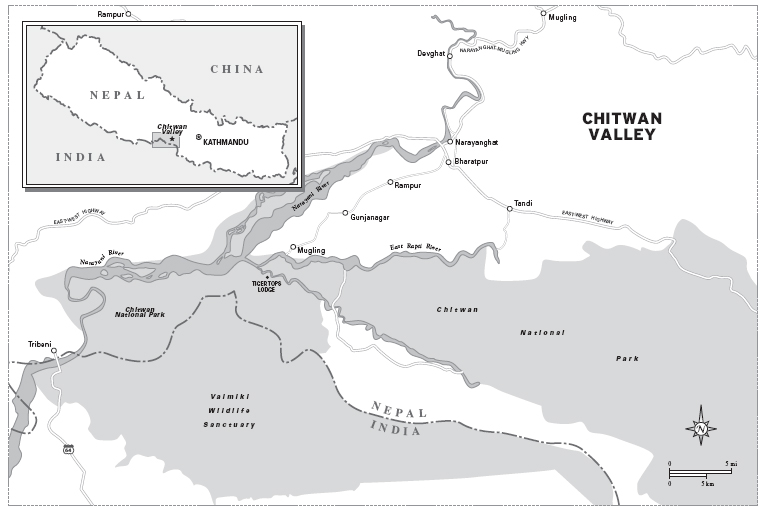

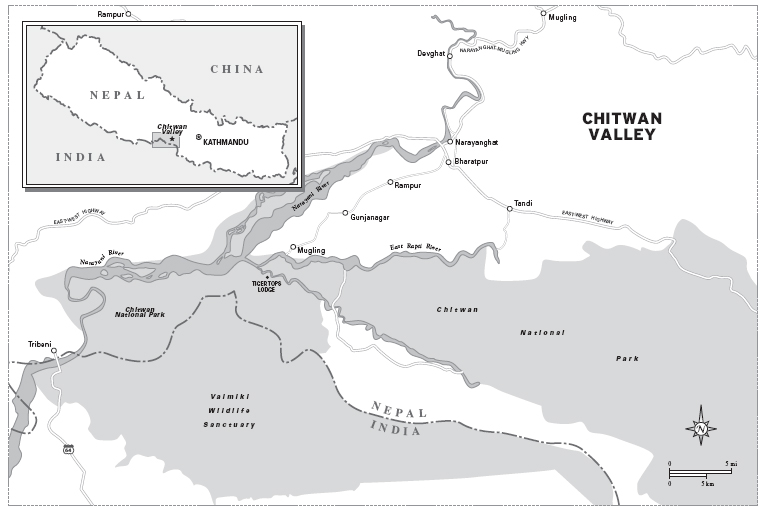

Map of Chitwan Valley by Stephanie Poulain

Distributed by Publishers Group West

For Parvati Parajuli

CONTENTS

AUTHORS NOTE

To write this story, I have relied heavily on memory but have also drawn from research notes, personal journals, and interviews (some recorded on tape in Nepali). All the events described here did take place, although some people may remember them differently. I have not, as far as I can remember, invented any events or exaggerated their details. For the sake of readability, I have, of course, omitted much, but I have not consciously compressed or moved events around in time. Nor have I created composite or fictional characters. For those who shared their lives and stories knowing they would be made public, I use real names. Where I have doubts about permission to publicize, I have changed names.

NOTES ON TERMINOLOGY

For simplicity, I use the term caste rather than more accurate terms like jatiendogamous kin and occupational groupsand varnaa ritual taxonomy that arranges jati into hierarchies.

In the same spirit, I use Hinduism and Hindu as convenient catch-all terms for philosophies, groups, and people while recognizing that there is no singular Hindu religion with one founder, one text, one god, or one institution. It would be more accurate to speak of Brahmanism (or Vedantic Brahmanism), Vaishnavism, Shaivism, Bhakti, and so on.

Rather than the foreign word Nepalese, I use Nepali to refer to anything of or from Nepal: the language, the people, the food.

B Y THE TIME light slivered Nepals horizon on that November morning in 1987, Id already spent forty hours in labor. The earliest contractions may have been false labor. But I cant pinpoint when the pain turned from false to true. Or where the feminist anthropologist in me ended and the Brahman wife began.

I dont remember much beyond pain. Yet from the loft I shared with my husband, Pramod, over the buffalo shed, we must have heard the usual dawn chorus in the family compound: the ku-ka-RI-ka of roosters, the monotone chants of my father-in-law reading the Vedas, creaks and splashes at the water pump, the whiz and ping of milk squirted from buffalo teat to tin pail, shouts to bring this or that and hurry up, some Hari-Shiva-Narayans for all that had to be done. No matter what, animals had to be tended, food prepared, gods and goddesses worshipped. And cursed.

Pramod sat beside me on our bed. For days, he had hovered nearby, only leaving to bathe, visit the outhouse, or fetch whatever I asked for. Yet, like many women in labor, I could not remember what had ever attracted me. The wide, full lips? The silly puns and optimism? The brown eyes and how they curved up at the outer corners?

Voices murmured in Nepali in the background: Why is it taking so long? Whats wrong?

For once, Pramod stopped trying to console me with words. Through the rise and fall of each scream, he rubbed my back. Even my mother-in-law, Aamawho tried to please everyonehad given up trying to please me. She brought no more eggs floating in soup, eggs burned in ghee, or other culinary experiments Id never before seen served in Nepal. She squatted nearby, her face paler than usual. Between contractions, I wondered why she didnt refasten oiled strands of white hair that had fallen loose from her tight bun.

Years later, I troll for memories and snag a sense of myself as driftwood: bleached and bloated, smashed onshore, pulled out beyond the breakers to rest a moment, then picked up by a cresting wave and slammed on sharp rocks again. At times, a finlike thought breached: make a decision by morning. Then, morning came. But I didnt want the bother of deciding whether to go to the hospital. I wanted sleep, and pain was the fee I paid every few minutes for another ride on the lullaby swells behind the surf.

Neither here nor there, I think now. Id often heard Brahman women in our village sum up their lives like that. Belonging to the highest caste in Nepal, they enjoyed some privileges. But they also had to follow strict rules to uphold ritual status and keep ancestral lines pure. On marriage, they leave their maitimaternal hometo spend the rest of their lives in their ghartheir husbands extended household. They never return to the place they feel most at home, except to visit. Nor can they be full members of the place where theyll live until death. Yet, by giving birth to children, especially sons, a woman crosses a threshold where, with skill and luck, she can claim some power in her ghar.

My maiti was Seattle. When homesick, I most longed for the driftwood-strewn beaches of Puget Sound where Id grown up snorkeling, digging clams, and collecting shells.

My ghar was landlocked in Chitwan Valley, a wide basin in Nepals taraia narrow strip of lowlands that belts the base of the Himalayan foothills before the Indian subcontinent drops southward and flattens out into the vast Gangetic plains. Flanked on the west by the Narayani River and on the south by the low Siwalik hills along Nepals border with India, Chitwan used to be marshes, grasslands, and jungles. An influx of foreign aid after World War II transformed Chitwan to farmland. In a country outsiders have long associated with mountains, exoticism, and poverty, Chitwan began to draw Nepali newcomers with flatness, practicality, and opportunity. Residents often likened it to the United States, whereso they had heardpioneering immigrants had driven out indigenous peoples and wildlife, felled trees, drained marshes, planted grain, and built great towns and cities.

Next page