Hatherleigh Press is committed to preserving and protecting the natural resources of the earth. Environmentally responsible and sustainable practices are embraced within the companys mission statement.

Visit us at www.hatherleighpress.com and register online for free offers, discounts, special events, and more.

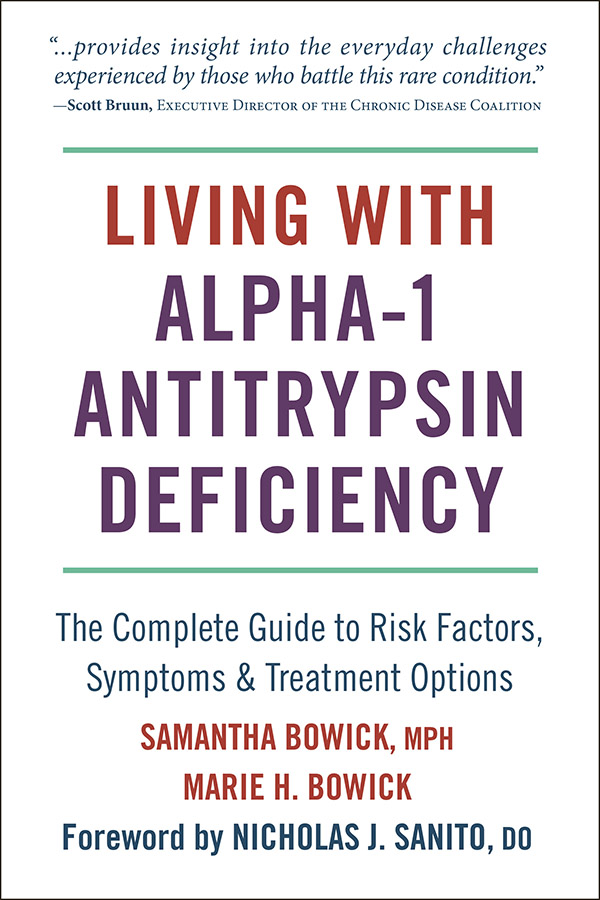

Living with Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency

Text copyright 2019 Samantha Bowick

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available upon request.

ISBN: 978-1-57826-809-2

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher.

Interior Design by Cynthia Dunne

Cover Design by Carolyn Kasper

Printed in the United States

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The authors of this book are not medical professionals and make no claims otherwise. The goal of this book is to provide patients and the public with information about Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency through one patients story of living with the illness.

FOREWORD

W HO KNEW she had a genetic disorder? At first blush, it seemed so simple and straightforward: Marie smoked cigarettes, had abnormal lung function tests, and had breathing symptoms, namely cough and shortness of breath. This was a typical case of self-inflicted COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) and emphysema.

Treatment would be straightforward as well: prescription inhalers to improve (or at least stabilize) lung function, thereby relieving symptoms. Of course, quitting smoking was strongly advised at every office encounter as well.

As time went by, however, things were not so straightforward. Maries symptoms progressed more severely and rapidly than expected for a typical COPD patient, despite the use of newer, state-of-the-art medications. Her lung function tests showed a precipitous decrease in just one years time. Something just didnt fit. So at that point we did the test. Sure, we had checked a few patients in the past, but the tests always came back negative; the condition is so rare, those results were no surprise. Surely, Marie would be no different.

But she was different. The test showed a profound deficiency of alpha-1-antitrypsin, rendering Maries lungs susceptible to tissue destruction and the development of emphysema, regardless of cigarette smoking. The toxins in cigarette smoke simply accelerated the process, causing loss of lung function essentially right before our eyes.

A new approach had to be taken. First, smoking had to stop. There was no further need to recommend or encourage Marie to quit. Second, augmentation therapy had to start. This meant a commitment to receiving weekly intravenous infusions of alpha-1-antitrypsin therapy, to replace (augment) the alpha-1-antitrypsin protein that her body was not producing. The goal of treatment would be to slow or stop the process of further lung tissue destruction. Unfortunately, augmentation therapy could not repair the lung damage that had already been done.

Ten years later, with her daughter Samantha still a driving force involved in her health care and well-being, Marie continues to battle. She relies on continuous oxygen therapy, on inhalers, on nebulized respiratory treatments, on physical therapy, and strong family support.

To be sure, Marie is short of breath, certainly limited in her ability to perform routine day-to-day activities. Showering can be exhausting. Housework is nearly impossible. Nevertheless, she marches on. Every week she has a nurse come to her home, receiving her augmentation therapy, trying to hold on to the compromised lung function that remains. The future is uncertain, but she remains hopeful.

Dr. Nicholas J. Sanito, DO, pulmonologist

What is Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency?

A LPHA-1 ANTITRYPSIN deficiency is an incurable disease.

There is much that we dont know about alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, or A1AD, but this much is certain: modern medicine does not yet have the ability to cure an individual with this condition.

A1AD is a rare disorder: somewhere between 1 in every 2,000 to 5,000 individuals is afflicted by it, or between 0.050.02% of the population, who recognized a connection between low plasma serum levels of AAT, or alpha-1 antitrypsin, and symptoms that at first glance looked quite a bit like emphysema. Unfortunately, this means that Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, as a newcomer to the medical community, hasnt received all that much research conducted compared to other illnesses.

So what do we know about A1AD? We know that it occurs when a persons liver does not produce enough of the protein alpha-1 antitrypsin, which the lungs need to function properly and it also serves to protect them from damage.

The lower the amount of alpha-1 antitrypsin protein present in the body, the higher the risk of having emphysema, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or another related illness because of the way the liver protein impacts overall lung health and function. This, in turn, creates a cascade effect of illness and lowered functionalityour bodies simply cannot function properly if our lungs are not able to inhale and expel oxygen and carbon dioxide correctly.

Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency doesnt cause chronic pain, but it is a chronic illness (meaning symptoms last longer than a few months). Therefore, A1AD is not an acute condition (placing it in the same category as emphysema and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease). Without augmentation therapy, patients will die quicker than they would if they received treatment. As with emphysema and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, once the lining of the trachea, bronchi, alveoli, and other structures aiding in breathing are damaged, they cant repair themselves, causing many of the symptoms experienced by patients.

CAUSES OF A1AD

But what causes A1AD? Truth be told, were still a bit in the dark on that, as well. We know that genes play a major role in someone having alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. Theres a simple denotation used when discussing the genetic component of this disease: a person with the MM genotype are considered normal; they do not have alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. Those who do manifest the disease have been found to have the ZZ genotype. By the notation used for expressing genetic information, then, a carrier of the disease will have the MZ genotype. Being a carrier means that, while you do not show symptoms of the disease itself, your genetic code contains the potential to develop A1AD; therefore, if you were to have a child with someone of the MZ or ZZ genotype, you run an increased risk of the child developing A1AD. There is not much research about carriers being affected or showing symptoms; carriers can monitor their risk by having their doctor perform routine lung function tests.