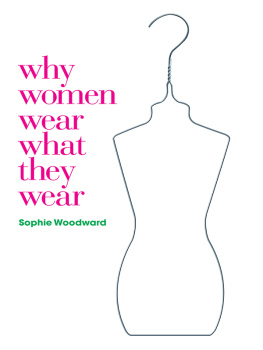

Costume Society of America series

Phyllis A. Specht, Series Editor

Also in the Costume Society of America series

American Menswear: From the Civil War to the Twenty-first Century, Daniel Delis Hill

American Silk, 18301930: Entrepreneurs and Artifacts, Jacqueline Field, Marjorie Senechal, and Madelyn Shaw

As Seen in Vogue: A Century of American Fashion in Advertising, Daniel Delis Hill

Clothing and Textile Collections in the United States, Sally Queen and Vicki L. Berger

M. de Garsault's 1767 Art of the Shoemaker: An Annotated Translation, translated by D. A. Saguto

A Perfect Fit: The Garment Industry and American Jewry, 18601960, edited by Gabriel M. Goldstein and Elizabeth E. Greenberg

A Separate Sphere: Dressmakers in Cincinnati's Golden Age, 18771922, Cynthia Amnus

The Sunbonnet: An American Icon in Texas, Rebecca Jumper Matheson

D RESSING MODERN MATERNITY

The Frankfurt Sisters of Dallas and the Page Boy Label

KAY GOLDMAN

Texas Tech University Press

Copyright 2013 by Kay Goldman

Unless otherwise indicated, illustrations are courtesy of Penny Pollock and Gigi Gartner, representatives of the Frankfurt Family Collection, subsequently donated to the Texas Fashion Collection.

Winner of the 2012 Lou Halsell Rodenberger Prize in History and Literature.

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, including electronic storage and retrieval systems, except by explicit prior written permission of the publisher. Brief passages excerpted for review and critical purposes are excepted.

This book is typeset in Scala. The paper used in this book meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R1997).

Designed by Kasey McBeath

Jacket photos: Maternity fashions by Page Boy shown February 18, 1947, and June 17, 1957. Courtesy the Frankfurt Family Collection.

This book is catalogued with the Library of Congress.

ISBN (cloth): 978-0-89672-799-1

ISBN (e-book): 978-0-89672-809-7

Printed in the United States of America

13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 / 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Texas Tech University Press

Box 41037 | Lubbock, Texas 79409-1037 USA

800.832.4042 |

This work is dedicated to three remarkable women: Edna Frankfurt Ravkind, Elsie Frankfurt Pollock, and Louise Frankfurt Gartner, who envisioned the idea that became Page Boy Maternity Company. Without their inspiring work, there would be no story to tell. It is also dedicated to the Jewish women of earlier generations who believed enough in themselves to break down barriers and become businesswomen. They refused to be limited by naysayers. They made it easier for those of us who came later to dream and, by dreaming, to achieve.

Illustrations

Patent 2,141,814

(Frankfurt Patent figure 1 & 2)

Patent 2,141,814

(Frankfurt Patent figure 4 & 5)

Acknowledgments

I owe a profound debt to many people who helped me bring this remarkable story to life. My mother told me the story about three Jewish sisters she knew when she was growing up in Dallas during the 1930s. She described their accomplishments, explaining to me that they had been granted a patent for their unique design that became the first real maternity dressa dress that made pregnant women look fashionable. Without her story in the back of my memory, I would never have started this project.

My editors have been amazingly supportive. First I would not have imagined turning my short presentation into a book without the encouragement and support of Judith Keeling. She and Joanna Conrad were ever ready to answer my questions and allay my uncertainties.

I also owe much to members of the Gartner, Pollock, and Ravkind families, who shared their memories about the Frankfurt sisters, were willing to answer my incessant questions, and made copies of photographs for me. I want to especially thank Gigi Gartner, who coordinated my interview with her mother, Louise Frankfurt Gartner, and her mother Louise, who graciously allowed me to visit her in her home. Furthermore I am immeasurably indebted to Penny Pollock, who made it possible for me to have in my possession the wonderful scrapbooks kept by her stepmother, Elsie Frankfurt Pollock, and for providing information about the last years of Page Boy's existence. Other family members also willingly shared their memories with me: these include Brenda Berg, Joan Susman, and Morris Weiss.

I was able to add details to this story because I received help from many librarians. I want to especially thank my friend Bill Page from Evans Library at Texas A&M, who is always willing to assist me and is continually on the lookout for information he believes I can use. I also had assistance from other Texas A&M librarians: Anne Patterson, from the West Campus Library; Laura Sare, Government Information Librarian; and Joel Thornton, Business Librarian. I also want to thank Edward Hoyenski, Collection Manager, Texas Fashion Collection at the University of North Texas. Without his help I would not have uncovered the wonderful Kennedy dress. I also had help from Marianne Martin from Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Debra Hughes, and Linda Gross from Hagley Museum and Library.

Finally, I want to thank my fantastic daughter, Dorie Goldman, who helped me focus my thoughts when my writing wandered and generously agreed to be my first reader.

Introduction

I n 1938 two optimistic young women gathered together $500 and began a new business: designing and manufacturing maternity clothing. Within a few years the business, Page Boy Maternity Clothing, became the foremost maternity clothing manufacturing concern in the United States. Page Boy's phenomenal growth also enabled a Dallas, Texas, entrepreneur to become the first woman inducted into the Young Presidents Organization and led to the firm's recognition as an innovator in marketing and clothing design.

Elsie Frankfurt, along with her sisters Edna and Louise, turned a revolutionary idea into a novel and successful manufacturing venture. The success of the business, Page Boy Maternity Corporation, was based on an innovative design that allowed a maternity skirt to fit snugly around the hips while making allowances for an expanding abdomen. This design prevented the skirt from hiking up in the front. Previous maternity dresses often rose up over the abdomen making the skirt front appear shorter than the sides and back. Dressmakers had not been able to solve the challenge of the short skirt, but Elsie Frankfurt was able to overcome this problem. Elsie's design, based on engineering principles she had learned in her design classes, earned her and her sister Edna a patent.

The mere fact that Elsie and Edna considered obtaining a patent is remarkable. Although Edna worked as an executive secretary for an oil company and Elsie had earned a college degree, these young women were not sophisticated entrepreneurs who had set out to revolutionize the maternity fashion world or any other business. Nevertheless, once they had the design they realized that it needed to be protected by a patent, and with that step of patenting their design, they joined a small group of innovative women who had previously applied for and been granted patents.

United States patent law originated from the Constitution, and the first patent act was passed by Congress in 1790. United States patent regulations recognize three main types of patents: utility, design, and plant. The utility patents are typically machines or items of use. Design patents are items like Elsie's skirt, or a particular patented design for the shape of a bottle, or some other useful item. The plant patent was granted for the asexual reproduction of new plants such as hybrids. Although the patent office does not keep records of the gender of those who receive patents, patent office records indicate that the first woman to be granted a patent was Mary Kies, who earned a patent for straw weaving with silk thread. That patent was issued on May 5, 1808.

Next page