PREFACE TO THE 2003 EDITION

Elizabeth Martinez

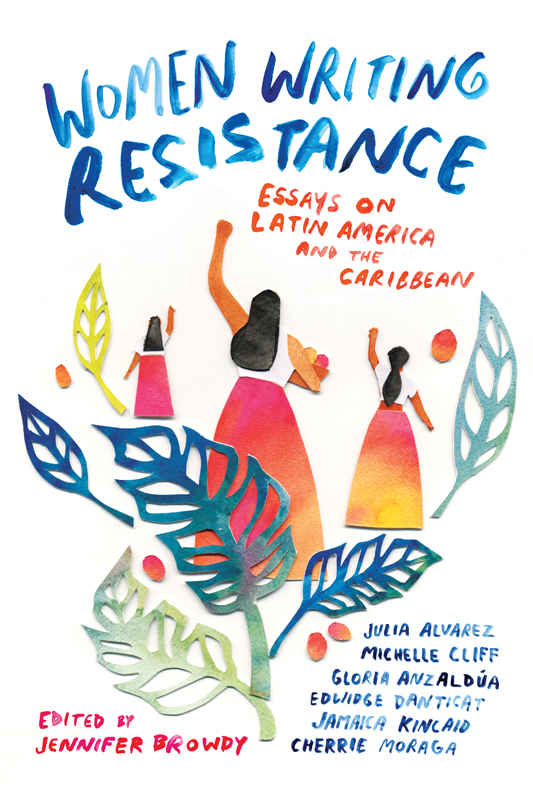

THIS EXTRAORDINARY COLLECTION... I could begin that way, but no. Those words, though true enough, seem all too inadequate. The book ishere comes a risky claimrevolutionary. But why? An encouraging number of anthologies of writings by women of color have appeared in recent years, with This Bridge Called My Back, edited by Gloria Anzalda and Cherre Moraga, leading the way. That development ended decades of invisibility. Now comes Jennifer Browdys book, offering new reasons to celebrate.

There is, first, the welcome fact that her book focuses on Latin America and the Caribbean, those huge expanses of our hemisphere too often ignored or minimized in the past. Except for academic specialists, few people, even on the left, paid much attention to Latin America until thousands of indigenous rebels rose up in southern Mexico [in 1994, in response to the North American Free Trade Agreement]. And the Caribbean exists in the minds of many North Americans mostly thanks to a unique, struggling revolution in Cuba that wont go away. Although we see more attention given to this region today, there is still too little awareness of the many peoples, histories, and cultures that the women writers in this book so eloquently and passionately illuminate.

Their stories of resistance to oppression are also global, for the conditions they present exist worldwide. These writers cry out against the effects of colonization, unfettered imperialism, and corporate globalization on billions of people, as well as on the planet itself. Their rage is haunting. Who can forget the saying of poor Haitian women under slavery and colonial oppression, as recalled here by Edwidge Danticat: We are ugly, but we are here? And here to stay, Danticat adds. Every once in a while, we must scream this as far as the wind can carry our voices, she writes.

The books call for such defiance is not new. Since September 11, 2001, the need for it has been greater than ever, as the US response to that dreadful day continues sending its dreadful message: ours is an age of intensified empire-building in which no war is unthinkable.

It is also an age of galloping globalization for the benefit of capitalist growth. In our hemisphere, the suffering caused by NAFTA has not halted the drive toward more of the same alphabet. Todays Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA), and a similar plan for Central America (CAFTA), move forward that caravan of misery.

Around the world we find institutions like the World Trade Organization (WTO), whose policies could mean starvation for three billion peasant farmers, according to Samir Amin, director of the Third World Forum in Senegal. Unable to grow foodstuffs that can compete with products imported from advanced countries, how can these people survive? When Kyung Hae Lee, a Korean farmer, committed suicide at this years [2003] WTO meeting in Cancn, Mexico, he was protesting a deadly greed that should enrage us all. His suicide was a desperate call for more of the activist commitment that fills the pages of Women Writing Resistance.

The book is a collective Declaration of Resistance to the power and arrogance of ruling-class, racist, patriarchal domination. Its call for resistance also imagines a transformed world. These women offer visions that are profoundly revolutionary, and they do so with great beauty. In offering this wealth of prose and poetry by some of the worlds finest writers and strongest feminists, Jennifer Browdy confirms that politics and art cannot be separated, despite the critics who try to do so.

Finally, Browdy offers us a shining, elegant introduction that makes the totality of her anthology a work of art in itself. Gracias, Jennifer, y venceremos!

INTRODUCTION

WRITING RESISTANCE, ENVISIONING THE BETTER WORLD THAT COULD BE

Jennifer Browdy

WOMEN WRITING RESISTANCE : Essays on Latin America and the Caribbean chronicles a time of intense awareness of the effects of globalizationthe transnational movements of capital and of peopleand of a heightened awareness of the porousness of borders that used to seem firm, especially national and cultural borders. Old categories such as First World and Third World are no longer neatly mappable, and the old divides of nationality, language, and race have become much more fluid. The contributors to Women Writing Resistance range across all these borders, locating themselves in the borderlands between Latin America, the Caribbean, and North America, even as they call into question the validity of such labels as signposts to identity.

From Latinas of various national origins, many now writing in exile, to writers of Anglophone and Francophone Caribbean origins, to members of the Hispanic Jewish diaspora, to Chicanas who culturally straddle the US-Mexico border, to Puertorriqueas with their special hybrid American political status, and even including one North American of European Jewish ancestry, Margaret Randall, whose lifetime of commitment to social justice movements in Mexico, Cuba, Nicaragua, and North America make her an inveterate border crosserthe contributors to Women Writing Resistance exemplify the possibility of coalition and alliance among women from widely divergent backgrounds, all working in what Aurora Levins Morales calls the field of cultural activism to envision and manifest a more equitable, peaceful, and sustainable future for the Americas and the world.

Beyond their commitment to social justice, the authors included in Women Writing Resistance are outstanding writers, garnering international acclaim for their novels, poetry, and essays, which often make use of formal innovations such as linguistic code switching, oral history, authorial collaboration, and the creative juxtaposition of previously pure genres such as poetry and prose or fiction and nonfiction, all in the service of textualizing previously marginalized, culturally complex voices. All the contributors have enacted in their writing what Mary K. DeShazer has called a poetics of resistance, in which writers participate in resistance by inscribing it in beautiful, powerful poetry and prose.

To understand these writers resistant politics, we must explore the history of Latin America and the Caribbean, which forms the backdrop of their work. Globalization as a socio-historical phenomenon has been going on for a long time: it began to assume its current configuration roughly five hundred years ago, when the age of European imperialist domination of the peoples of Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and the Americas began. This Euro-American cultural hegemony has always been accompanied by various kinds of resistance movements. In Latin America and the Caribbean, the initial goals of resistance were to throw off the twin yokes of colonization and slavery, goals that were for the most part accomplished by the mid-twentieth century.

But the eradication of slavery and the arrival of nationalist and independence movements did not do much to improve conditions for women and other racial/cultural minorities, or for the poor in general, throughout the region. Social codes that privileged light skin (as evidence of European ancestry) persisted, and women continued to be confined to restricted areas of the patriarchal compound, pinned down by the male supremacist code known as