Table of Contents

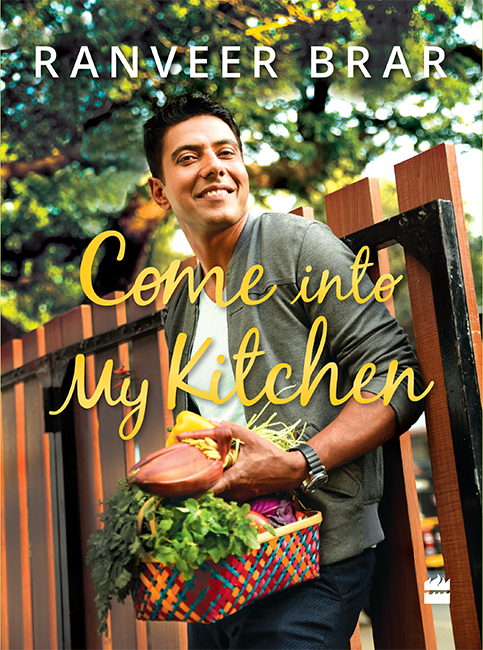

RANVEER BRAR

Come into

My Kitchen

HarperCollins Publishers India

This book is dedicated to my parents for their undying faith in me and for passing down the belief that doing good isall that matters in the enda value that dictates my actions till date

Contents

SECTION

Biji and Pitaji

Biji was something of a fanatic when it came to not wasting food.

I was born in Lucknow, in 1978, into a family of Punjabi zamindars. Its an aspect of my life that is not well-known. Ours was a tightly knit family of farmers originally from Punjab. We had our own farms, our own cattle and our own livestock. My father was an engineer, my mother, a homemaker, and we lived with my grandparents in an old haveli near our farm in Telibagh village, Lucknow. I had a very strong bond with my grandparents, biji and pitaji, and my parents.

My father is a logical, straight-thinking man. I get my business acumen from him. My mother, on the other hand, is my artistic inspiration. I credit her for my creative ability. She always encouraged me to paint more, sculpt more and write more. Thanks to them I am a good balance of both business acumen and creativity. It has helped me understand food and prepare great food in a great variety of spaces. But I am moving ahead too fast. The story of food came into my life much later. Before food, there were many influences that made me the person I am. Besides my parents, my grandparents gave me a firm grounding in traditional values. While growing up, I spent a lot of time with themtaking long walks with my grandfather, spending hours in the kitchen with my grandmother and wandering around our farms.

My grandmother had a big influence on my life. A generous, beautiful soul, she was the one who first introduced me to the priceless concept of barkat. Loosely translated, barkat means benevolence. More a concept rather than a tangible thing, it is an immeasurable blessing that is bestowed upon a cook as a result of their good practicesborn out of respect for their ability to save, and for their patience, good character and virtuousness. Biji always said, If we have all that, then we are blessed with the barkat to be good cooks. My grandfather, an ex-army man, too had strong, extremely philosophical views on life. I would hang on to his every word all through our habitual morning and evening walks, often not understanding but always absorbing everything. Our conversations exposed me to advanced thoughts and opinions at a very young age. I remember him saying, Whatever comes, always remember that at the end of the day you are an insan and never forget your insaniyat. Never stop being human ever. A valuable lesson I try to live up to every day of my life. A lesson that I strongly feel has made me a better person.

Growing up on a farm, we were close to nature. My childhood summer vacations were spent helping on the farm, threshing wheat, guarding the farm from stray cattle, and milking cows. The farm was our livelihood and our source of food. It was the world I was born into and grew up with. Today we talk about farm to table and the importance of supporting the local farmer. Farm to table is what I had every day, till I turned nineteen and went to college. Ghar ka doodh, ghar ka anaj, ghar ki dal, ghar ka ghee is what I was used to. I dont remember ever going out and buying wheat or lentils. That experience is what I still live with today, and it is an important facet of the chef I became in my later life. Layers were added as I grew up, but I had a deeper relationship with food because I had watched grain ripen in our fields and grown vegetables on my own. One does not forget this kind of grounding. It forms the very foundation of your relationship with food.

My first real interaction with foodbeyond the obvious act of eatingwas at the age of five. My grandparents thought, He is young and its good if he goes to the gurudwara. So I was dragged to the gurudwara. My grandfather felt at home with his fellow ex-servicemen, who congregated at the Hudson Lines gurudwara in Lucknows cantonment area. This is where I was taken every Sunday. At first I just sat around, clueless, not knowing what was going on. Until one day when I somehow ended up in the langar area. Langars are community kitchens where members of the community come together to cook and eat together. Helping in the langar is considered a form of sewaselfless service to the sadhsangat (community), the gurudwara, and the world outside. I learnt all this much later, of course. At that point I had simply found some action!

After that, the langar became my favourite spot at the gurudwarawatching, chatting with people, playing and, mostly, fooling around. It was a fascinating space where so much happened. A typical langar fed thousands of people and required tons of food, so there was massive activity taking place all day. In one area, men and women sat together around a huge rectangular platform covered in dough, shaping balls, rolling rotis and putting them on a massive tawa (griddle) built into the floor. The huge griddle, with rows and rows of rotis, had at least fifty people cooking on it at the same time. It was an efficient assembly line with volunteers using long flippers, turning the rotis over and over until they acquired dark brown spots, then flicking them off the griddle onto a cloth to be taken away while, almost immediately, another line would take their place. I would watch them for hours.

On another side, tons of dal and vegetables were cooked in enormous vessels big enough for me to swim in. To a child the gigantic pots and pans were magnified ten-fold! Cauldrons bubbled over wood fires constantly fed with logs, steam billowed, and the aroma settled in the air. Volunteers would slowly and rhythmically stir the food with long-handled khurpas (spatulas) to keep them from sticking. It took hours to cook one cauldron of langar wali dal. The kadah prasad was fascinating. I watched it boil from a murky liquid into a molten silky golden mass of halwa, the khurpa leaving furrows across its surface. It was mesmerizing.

Life continued like this for the next eight years or so. Every Sunday was spent watching people cook at the langar. Until one Sunday, when I was thirteen, someone observed me idling as usual and exclaimed, Oye, you! You come here and sit down and chat up everybodyyou better start cooking. So I was forced to cook. I cooked meethe chawal for the first time that day. I knew how it was done, but Id never done it myself. For some reason the food was well-made and from that day on my dad began calling me langari (someone who makes langar). I must admit there was no intense epiphanic moment for me there. Meethe chawal became my duty in the langar every Sunday after that. A duty I embraced with, perhaps, a tad too much fervour because it meant evading sermons. In retrospect, however, cooking at the langar taught me a lot. I learnt how to prepare food for a large group (a valuable lesson for any chef) and I understood the importance of a clean kitchen early on.

I did, unknowingly, also gain one more insight. A core Sikh belief is equality and this is epitomized in the food at the langar. Anyone is welcome to partake of langar regardless of sex, colour or religion. And because it is meant to be all inclusive, langars are vegetarian and free of any attached rituals. There are no conditions to partaking of langar and everyone is welcome to serve, cook or clean. Nobody leaves without eating. Food cooked in large quantities always tastes good in my mind, but langar food has a special flavour because it is cooked with so much positive energy, because it is prasad. After all the food is cooked, each dish is put on a plate and offered to the Guru. Once blessed by Him, it is mixed into the waiting cauldrons of food, thereby converting all the food to prasad. Because it is to be offered to the Guru, no one ever tastes the foodthat would make it