GRAMSCI

Introduction

Alfonso Borello

Gramsci: Introduction Copyright 2013 by AlfonsoBorello.

Revised Edition 2020 by Alfonso Borello.

All Rights Reserved.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in anyform or by any electronic or mechanical means including informationstorage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing fromthe author. The only exception is by a reviewer, who may quoteshort excerpts in a review.

Cover designed by Alfonso Borello

Smashwords Edition

Printed in the United States of America

First Printing: 2013

Second Printing: 2020

Villaggio Publishing Ltd

Contents

Preface

"Writing is becomingdangerous," wrote Antonio Gramsci. "This may lead to a new kind ofcommunication."

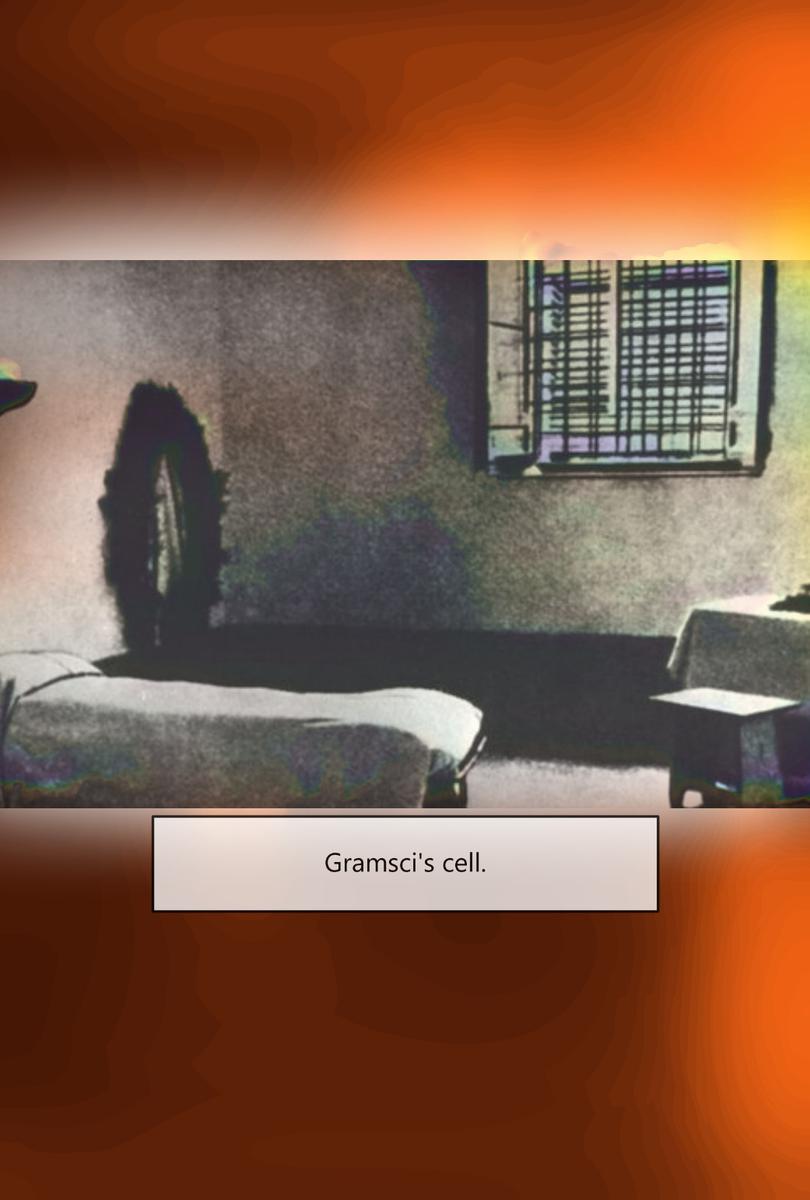

Gramsci hadplenty of time to read and write during his stint in prisontenyears is a miniature life.

As noted inmany references in his quaderni (notebooks), hefalls in love with the theories of Benedetto Croce (1866-1952), anItalian idealist philosopher who had no problem as a writer, andwas influential with history and aesthetics. Never laconic, Gramscielaborates Croce's ideologies, and, at times, makes contumeliousremarks to silence the haters. Giovanni Papini (1881-1956), anItalian essayist and novelist, Gramsci considers as non-so-great,is one of many.

As in his letters,Gramsci's style is harsh and provocative, and many ideas, andrants, seem to be his own, and original. "So many people crave tobe original,"

he wrote."People expect originality, and cheaply. Truth is, prisonsand manicomi (mentalinstitutes), are packed with original types. Nevertheless, everyrevolutionary is original. (!?)" He had an opprobrious passion (akeyword) for politics, education, people, and life in general.Unfortunately, many concepts and principles are not sufficientlyelaborated, scream for tacit approval, and seem to come straightfrom the narcotic kindergarten of knowledge of Hegel and Marx. Thelast one had enormous influence on Gramsci's pedestrian idea of'the trained gorilla' in the chapter on America. "Work is whatmakes us human and creative," said Marx, "but it is also anabstract idea, because stomachs need to be filled, and the wholething leads to alienation." A paradox?

The invectivestyle and faade of L'Ordine Nuovo , the paperGramsci edited in the northern commercial city of Torino (Turin),was never quite socialist, but communist; it was an iconoclasticmanifesto for ilrisveglio (the awakening).Gramsci received numerous warnings from the political police: hisvitriolic concepts on how to run a state weren't going to beextolled by the current administration. Eventually, Il Duce wouldlose his patience, and Gramsci was to be sanctioned. Mistakes weremade indeed, but media outlets needed to be more responsible, andabetting a revolution wasn't going to help. Defiant, as a goodradical, Gramsci added fuel to the

fire. The fascistswere going to lead with the iron rod and the intelligentsocialists(?) weren't going to take it. "A thing moves another.Mistakes or not, let us make our own mistakes." But wait, where arethe people? The book smart Sardinian meager man, soon stricken bytuberculosis, was too stubborn to submit. L'Ordine Nuovo becameless than a capstone, Gramsci's tone was too complicated for theworking class: Intellectuals. Assimilation and conquest. Saving.Gramsci's contribution to politics was either a debacle or atriumph. Perhaps martyr hood, or purification was theattainment.

It's aquestion mark over how many supporters Gramsci had. His readerswere intellectuals and fickle.Close friends and advisers, including family members, were probablyforced to distance themselves. His wife Julia and children fled toRussia. Gramsci was isolated. And sooner than later isolation leadsto catastrophe. Before his arrest, he had plenty of time to fleeoverseas and run his operation from there. In prison, all he neededwas a signature with a plea bargain, but he declined. He thoughtthat a strong sense of purpose would eventually survive thecollapse of fascism. He wanted to win at all costs. Wars arefought for different reasons, and there isnt anything such as justwar. The Church was monitoring the situation cautiously, but didn'tinterfere with Mussolini's beliefs. Benefit of the doubt or fear ofretaliation?

The endof fascism came too late. Gramsci struggles ended intragedy.

Even with somecriticism, any student of Marxist theory should find out more aboutAntonio Gramsci, because for many, his writings and notions arestill relevant today, even if his career could be seen as afailure.

Key points

Particularlyinteresting is the section on education, where he visualizesexperimental teaching methods with labs, for hands-on learning;made popular at the time in part of Europe.

In the Notebooks fromPrison , not TheLetters , Gramsci uses anintricate language. He was devoted to reading, he was anintellectual, and was articulate with words. The Englishtranslation doesn't seem, at large, to convey the true meaning ofGramsci's ideas. Fancy Italian, same for any neo-Latin language, isextremely difficult to translate. To cement some key points, withessential keywords, glance at the illustrations.

Alfonso Borello,

Gramsci: AnIntroduction,

revised secondedition, August 2020

Additional notes

At the end of this book you will find thelink to the original notebooks, in Italian. The document is notincluded in this writing: it is over 2,200 pages, with almost onemillion words. It's in the public domain. Even if you don't speakthe language, you can use it (especially students). Copy thesection you need or (better) print it as pdf and run the documentthrough Google Translate. Because of the current use of A.I (thelonger the document, the better), the translation is less academicand opinionated, but good enough with the use of the keywords (nottranslated) you'll find on the illustrations. The translation willresult in snippets of very usable notes, definitely lessopinionated than the academic version. Get them straight from thesource. (Skip the long entire section on theater's reviews. Dated1920, it was included for no reason; it was a reprint of theentertainment section from L'Ordine Nuovo.

Introduction

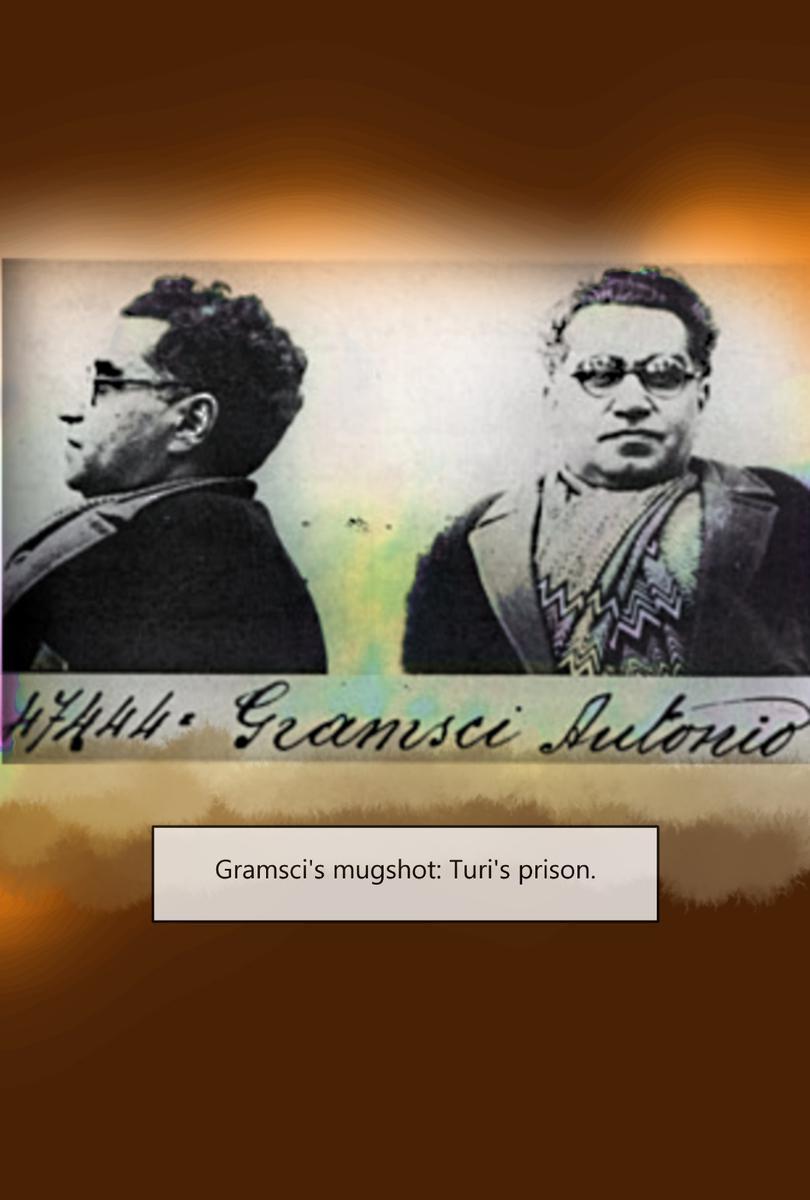

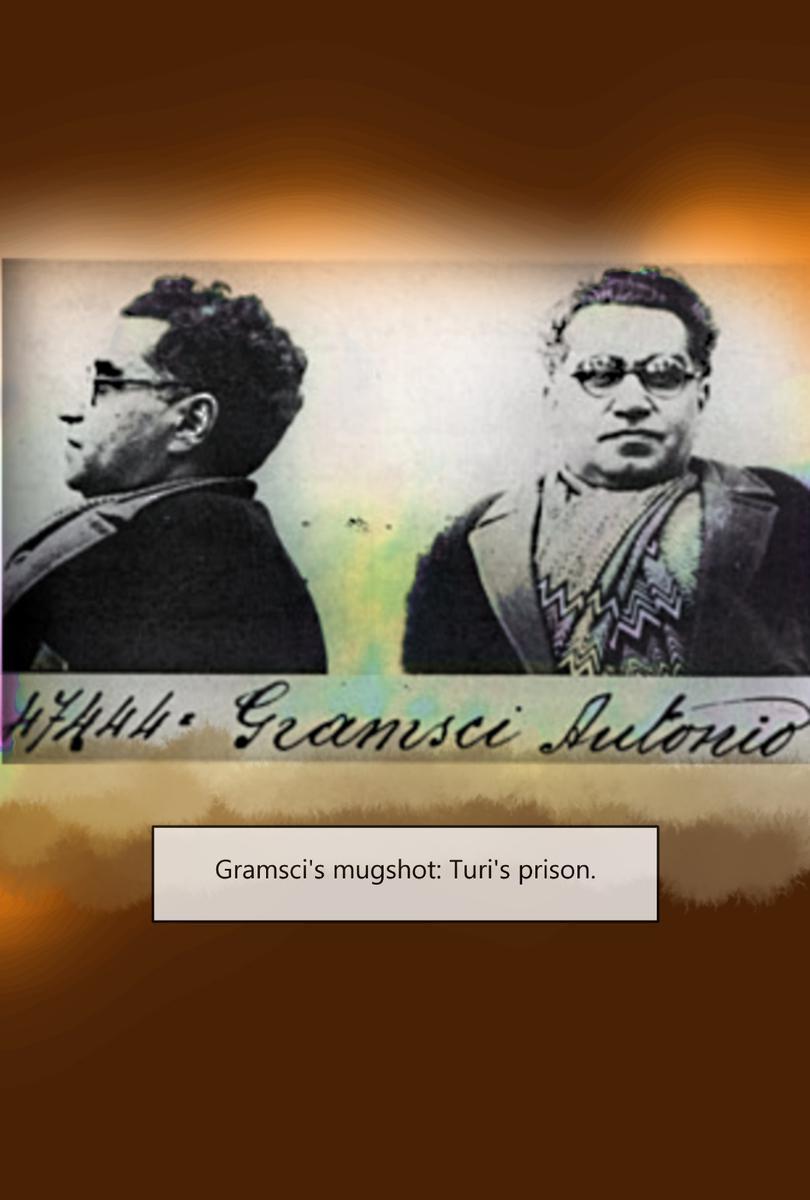

On November 8th 1926 Antonio Gramsci, anewspaper editor, Marxist thinker, and elected member of theparliament for the Italian Communist Party was arrested by theItalian Fascist police despite his parliamentary immunity, and sentto the Special Tribunal for the Defense of the State. The party wasoutlawed by Benito Mussolini during his regime, and Mr. Gramsci wassentenced to twenty years in prison for subversive propagandaagainst the power of state. He was relocated from one penitentiaryonto another for precautionary measures; Mr. Stalin himself madeseveral attempts to negotiate Gramsci's freedom via Comintern,because Gramsci's Russian wife Julia was the daughter of ApollonSchucht, leader of the CPSU and Lenin's friend. Unfortunately,Mussolini refused to negotiate and Gramsci spent years behind barswriting erudite essays on Marxist Theory, political leadership, andanalysis of culture; and numerous letters to his family andrelatives.

Next page