Is it any wonder that mankind stands open-mouthed before the bartender, considering the mysteries and marvels of an art that borders on magic?

F OREWORD

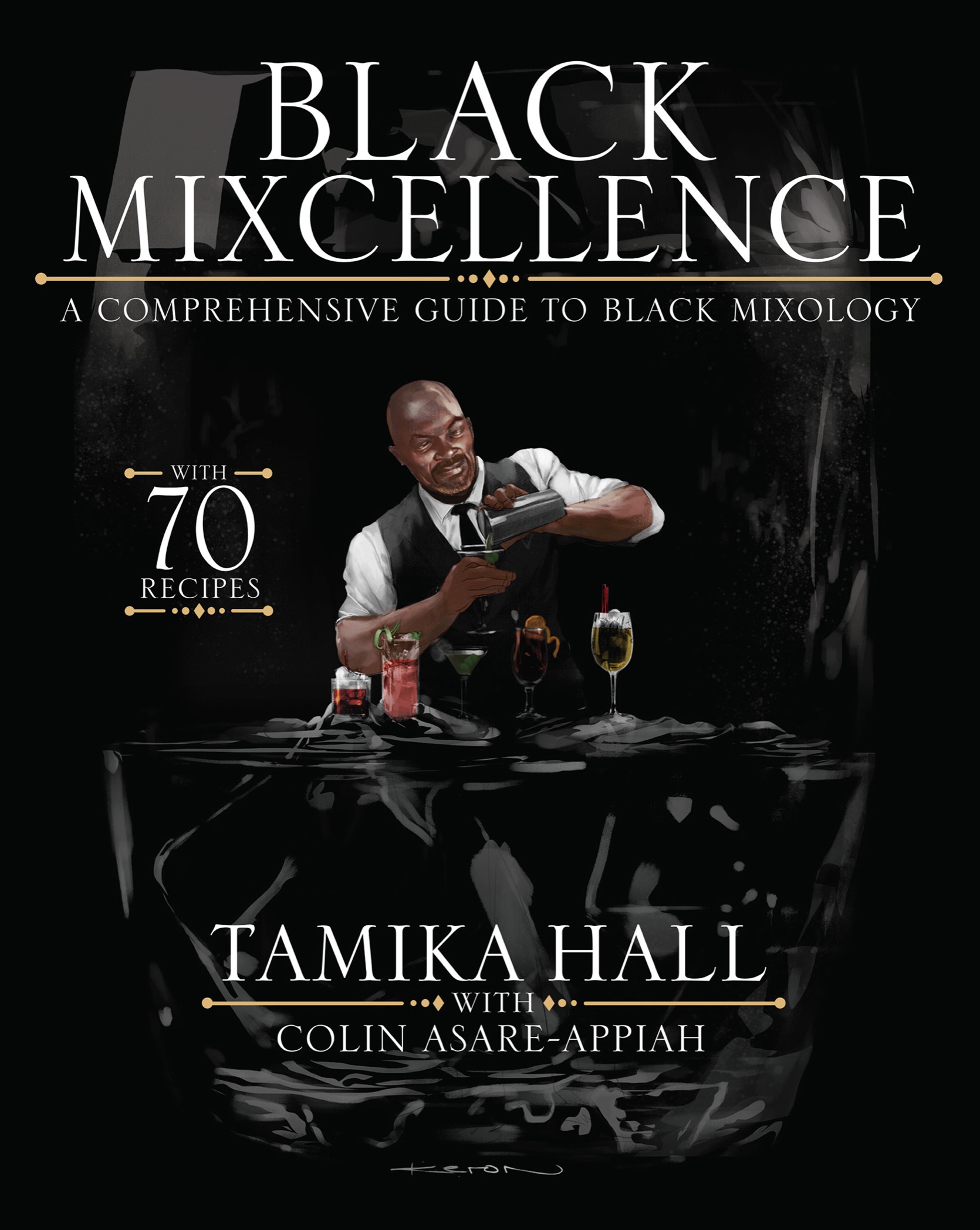

Recent research has celebrated some of the Black mixologists, including John Dabney, Tom Bullock, Cato Alexander, and the bartenders from the Black Mixologist Club, just to name a few. While their stories have been lost, Black people have been involved in the mixology industry since Europeans first came to America. Their creativity in cocktails such as the mint julep is legendary, and their contribution to distilling is still evident today in the whiskey and liqueur worlds. In recent times, opportunities are being afforded to Black mixologists to share their stories and to show their craft. Social media, and the public desire to re-create bespoke cocktails that people have enjoyed at bars and now want to make at home, have both been at the forefront of this movement to celebrate Black mixology. This celebration is long overdue, and as a Black mixologist, its great to see the opportunity, but a lot more work still needs to be done. Diversity only makes the industry stronger. Black mixologists bring a whole cultural pantry of ingredients and flavor profiles to the industry, which can only elevate the community as a whole.

Black Mixcellence delivers recipes from modern-day Black & Brown mixologists, including me (Colin Asare Appiah), Alexis Brown, Barry Johnson, Camille Wilson, Clay Coleman, Dessalyn Pierre, Ed Warner II, Ms Franky Marshall, Glendon Hartley, Ian Burrell, Jaylynn Little, Joe Samuel, Joy Spence, Karl Franz Williams, Kimberly Hunter, Madeline Maldonado, Marlena Richardson, Miguel Soto Rincon, Nigal Vann, Tiffanie Barriere, Douglas Ankrah, and Vance Henderson. These are just some of the Black mixologists who are blazing trails.

Tom Bullocks cocktail book, The Ideal Bartender, provides insights into the winter of the last golden age of cocktail culture. The book disappeared as Prohibition swept across the United States and has not been resurrected until recently. It is inspiring that the book was written in the first place, because just a generation earlier, having the ability to read and write could have been a death sentence for an African American. Our history has been oral for a reason, and now we have an opportunity to put our stories in print, and Ive always been a strong believer in writing our own histories. Because if we do not write it, others will.

Colin Asare-Appiah

P ROLOGUE

My first conversation about alcohol started in the second grade, when my first Holy Communion class exposed me to the idea that small children could drink wine in church. My parents drank wine at home, and I always wanted to hold a long-stemmed glass and sip, just like they did. I mean, wine was mentioned in the Bible, so it had to be goodright? The year of my First Communion was one of the longest years of my life. I had to study the story of the importance of wine to the Catholic religion. Learning the story and prayers was for a greater purpose, though in my mind, it was all so I could receive Communion and sip wine. I distinctly remember my First Communion and taking a giant sip of wine the priest snatching the chalice away and rolling his eyes as he wiped the spot where my mouth was. I felt so grown up and sat back in my seat with a wine-stained Kool-Aid smile. Youre supposed to say prayers after you receive Communion, but as I knelt down on the pew with my eyes tightly shut, all I kept wondering was, Am I going to be drunk soon?

Wine and spirits have always had a presence in my life as a woman with Cuban, Jamaican, and Geechee roots. Whether a rub because I was sick or a flavor enhancer in a traditional meal, spirits (particularly rum) played an integral role in my upbringing. My earliest memories of cocktails involved going out to dinner with my parents. For as long as I can remember, my parents always started dinner with cocktails: my mom with an amaretto sour and my dad with an old-fashionedor sometimes a continental, with Jamaican rum. My dad would pluck the cherry out of my moms amaretto sour and let me eat it. When I was a kid, the burn of the amaretto was intense, but the nutty almond aftertaste was elite. I looked forward to that moment at every dinner, and as I grew older, I developed my own dinner routine that also began with a cocktail.

At home, Wray & Nephew overproof white rum was a staple item. My aunt, who lived upstairs from me, had a bottle in the kitchen. My parents also had one in the kitchen, and my grandmother kept a bottle nearby at all times. When the bottle was finished, she would use it as storage for her coconut oil. That was one of the weird things I took from her house when she died. That bottle was a symbol of her kitchen, my family, and all the memories that came with it. She would mix malta con leche condensada when we came over and add Wray & Nephew in it for the adults. She mixed the nonalcoholic version with nothing but ice for the children. I still remember the first time I had the rum version; I was so excited to finally indulge. Nowadays, mixologists have refined the recipe and call that concoction a Malta Fizz. For me, its still malta con leche condensada, that drink my grandmother used to make. That drink, that bottle, and those memories help to tell my story. What I didnt know was that the rum and the cocktails were part of a bigger story that continues to unfold as time progresses.

Cocktails and spirits are all part of an industry that we, as African Americans, have played a major role in for years. Service and hospitality are tasks and interactions that African Americans have been providing the United States with for over four hundred years. Some of those tasks and interactions include mixology and the process of creating and serving cocktails. Given the parameters of slavery, service was something we were expected to deliver at all times. Even as such, we did it with a smile and still managed to make a lasting impression. Mixologists/bartenders do a job that requires a variety of skills and a tremendous amount of patience, customer empathy, and enthusiasm.

Like a lot of our contributions to the history of this country, credit wasnt given where credit was due, but the stories and narratives remain. While many of our ancestors couldnt document their journeys and stories as they happened, research allows us to piece together their accomplishments. This book serves as a home for some of our ancestors stories, contributions, and milestone moments that have greatly affected the mixology industry. BIPOC mixologists and bartenders today are trailblazers, making their mark in the very same industry. In ongoing efforts to preserve the stories of our ancestors from the past. Its only right that we concurrently document and highlight the recipes of some of the people making it happen in the