Thank you for buying this ebook, published by NYU Press.

Sign up for our e-newsletters to receive information about forthcoming books, special discounts, and more!

Sign Up!

About NYU Press

A publisher of original scholarship since its founding in 1916, New York University Press Produces more than 100 new books each year, with a backlist of 3,000 titles in print. Working across the humanities and social sciences, NYU Press has award-winning lists in sociology, law, cultural and American studies, religion, American history, anthropology, politics, criminology, media and communication, literary studies, and psychology.

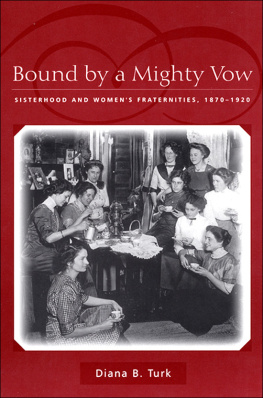

Bound by a Mighty Vow

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York and London

www.nyupress.org

2004 by New York University

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Turk, Diana B.

Bound by a mighty vow : sisterhood and womens fraternities,

18701920 / Diana B. Turk

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0814782752 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 0814782825 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Kappa Alpha ThetaHistory.

2. Greek letter societiesUnited StatesHistory. I. Title.

LJ145.K35T87 2004

378.198560973dc22 2004000272

New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper,

and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability.

Manufactured in the United States of America

c 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

p 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Preface

In the years spent researching and writing this book, I have learned that people are rarely neutral on the subject of Greek-letter fraternities. Some praise these organizations for their positive influences, while others condemn them as shallow, elitist, and unworthy of scholarly attention.

The purpose of this book is to explore the meaning of sisterhood for those who belonged to womens fraternities between 1870 and 1920. It is not to glorify or damn the female Greek system. Many times throughout this study I have felt pushed and pulled to take a position vis--vis fraternities. Supporters at times have wanted me to focus exclusively on the services they provided to members and the community services they performed. Detractors at times have wanted me to write a wholesale condemnation, citing what they see as fraternities selectivity, anti-intellectualism, and frivolity as the reasons for their position.

I have managed, I hope, to resist both of these pressures. The early history of womens fraternities is too multilayered and interesting for such simplistic approaches. In complicated and at times contradictory ways, womens fraternities both empowered and constrained their many thousands of members. It is my goal in this book to present a fair and accurate picture of their pasts. It is not to lay praise or blame on any person or group.

Acknowledgments

I could not have written this book without the support, guidance, and gentle prodding of many people. My deepest gratitude and indebtedness go to Hasia R. Diner, my adviser, mentor, and friend, who saw the value in this study even before I did and who, through her own example and constant support and guidance, pushed me to stick with the project and bring it to fruition. I am also grateful to the rest of my doctoral committee at the University of Maryland, College Park: Barbara Finkelstein, Gordon Kelly, and John Caugheyall three extraordinary teachers and mentorsand to my outside reader, astute critic Robyn Muncy. Thanks, too, to Eugene Tobin, Vincent Auger, and the late Sydna Weiss, professors at Hamilton College who nurtured my love of learning and encouraged me to enter academia.

I was extremely fortunate to attend graduate school with a group of wonderful, bright, fellow American Studies students: Jenny Thompson, Eric Olson, Deana Whitaker Greenberg, Dave Lott, and David Silver, all of whom offered support and critique as well as timely reminders of when it was time to put away work and meet at the Tick Tock or Bentleys. Special thanks go to Shelby Shapiro, whose intellectual challenges enlivened many a seminar and whose keen insight on early drafts of the dissertation and extensive feedback on final drafts of the book helped sharpen my arguments and clarify my prose.

I am also grateful to colleagues, present and former, in the School of Education at New York University, especially Robby Cohen, whose own careful scholarship coupled with his unfailing support for colleagues provide the best model possible for a junior faculty member to follow; also, Chelsea Bailey, Laura Dull, Kendall King, Cynthia McAllister, Joel Westheimer, and Jon Zimmerman, all of whom provided important feedback on various aspects of this project. Jessica Shiller did crucial research and copyediting for the book, and Emily Klein read and commented on nearly every single line and provided constant support and encouragement, as well as frequent reassurance that I would still be a good person even if I never did finish.

I also owe thanks to those who assisted me in my research: John Straw, former archivist of the Student Life and Culture Archives at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, who offered early and crucial guidance in shaping this project; Ellen Swain and Chris Sweet, also of the Student Life and Culture Archives, who helped with photograph selection and assisted on numerous additional tasks; archivists and librarians, too many to name individually, at the College of Wooster, DePauw University, Northwestern University, U.C. Berkeley, the University of Vermont, and the University of Wisconsin; and Noraleen Young, Kappa Alpha Theta staff archivist, who helped me locate many hard-to-find documents and assisted with photographs and fact checking. Special thanks go to Judy Alexander, former Fraternity Historian of Kappa Alpha Theta, who shepherded me through the hurdles of gaining access to fraternity archives; Lissa Bradford, former president of Kappa Alpha Theta and chair of the National Panhellenic Congress, who provided not only hours of oral history interviews but also encouragement and invaluable insight into the mechanisms of the fraternity world; Mary Jane Beach, president of Kappa Alpha Theta, who gave her blessing to my research; and Mary Edith Arnold, fraternity archivist of Kappa Alpha Theta, who guided me through the intricacies of nineteenth-century fraternity life, helped me secure documents and materials from other fraternities and sororities and served as my friend and fraternity guide throughout the duration of this project. In many ways, it was the interest of these women to know more about the history of their fraternity that made this project possible. For that and for their support for and trust in me, I extend my deepest appreciation.

I am also grateful to New York University for financial support in the form of a Research Challenge Fund Award and a Goddard Faculty Fellowship Award; Suzie Robinson Hoppe for offering me a home while conducting my research; anonymous readers who critiqued earlier drafts of the manuscript; and Emily Park and Eric Zinner at New York University Press.

More than to anyone, I owe my deepest thanks to my wonderful family: my mother, Barbara Turk, who is my greatest role model; my late father, Bob Turk, whose pride in me still sustains me; my sister, Karen Turk, whose critical eye, wisdom, and goodness I aspire to; my grandmother, Pearl Cohen, a model of true womanhood in every way; my mother-in-law Ellen Meisner, a most loving supporter; and most of all, my generous, loving, smart, funny person, Matt Meisner, and our little bundle, Gracie Rebecca.