Contents

Guide

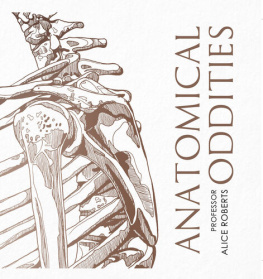

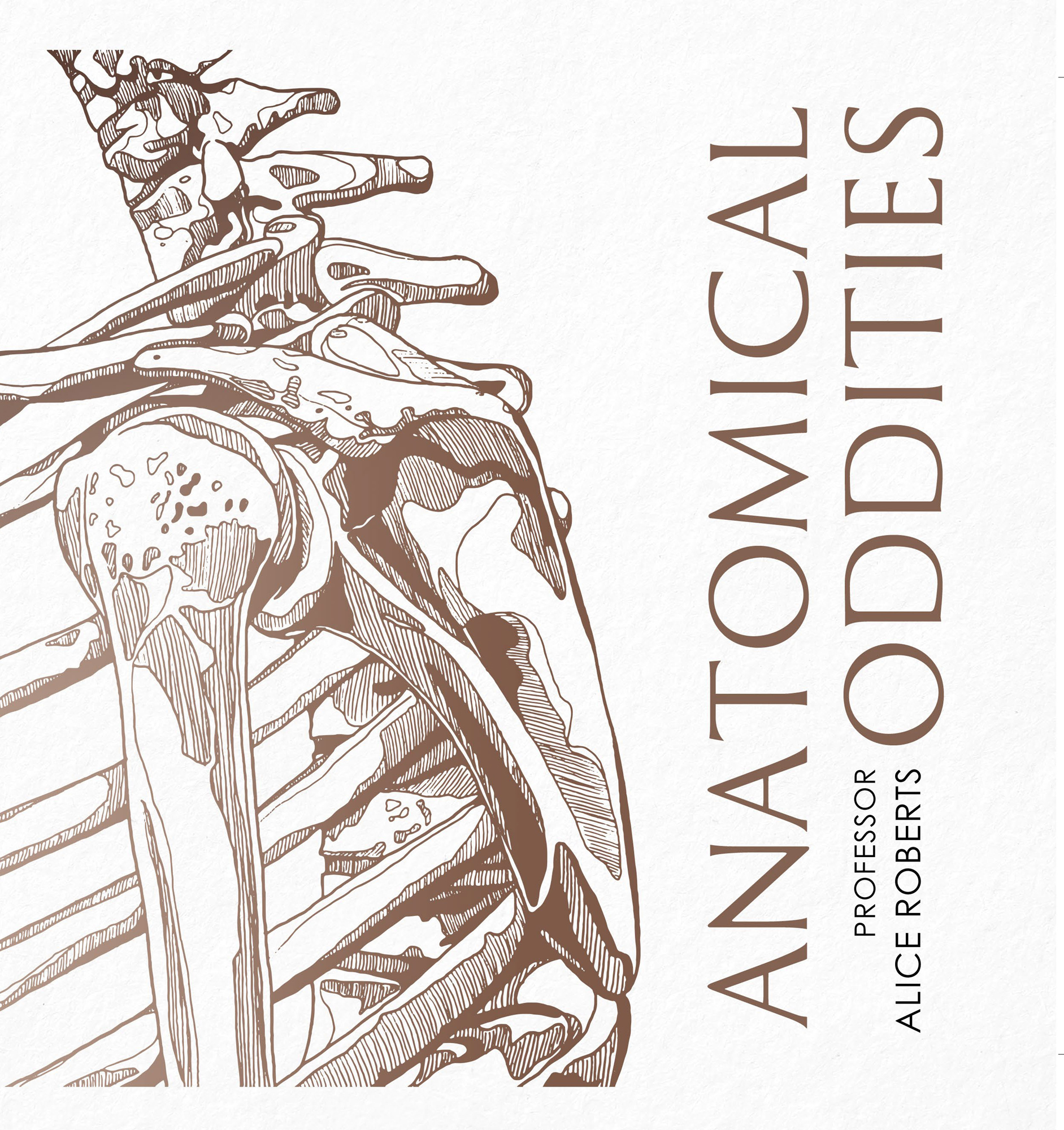

Anatomical Oddities

Professor Alice Roberts

For Jonathan

The beginning of education is the investigation of terms.

Antisthenes (446366 BCE)

The human body has been ogled, scrutinised, surveyed, chopped up and put back together, chopped up and not put back together; parts of it have been cut off, sliced up, put under the microscope; zapped with X-rays, buzzed with ultrasound, pierced with rods containing lights, tools and cameras; mummified, dried, plastinated, pickled. In the process, people have seen it from new angles, in new detail. And when you explore a landscape and discover a new feature in it what do you do? You name it.

The human body is littered with names so densely, not an inch of it escapes attention. Some of these names reflect what things look like the hippocampus of the brain looks a bit like a tiny seahorse; the mammillary processes of the vertebrae look like miniature boobs. Others tell you what things do levator labii superioris lifts your upper lip; levator ani lifts your bumhole. Some anatomical features are named after their discoverers or at least, the people who first wrote about them in detail. And many of these sound like mysterious places you might want to visit the islets of Langerhans or not the crypts of Lieberkhn.

Ive anatomised innumerable bodies and Ive always drawn anatomy to learn it myself, and to teach it to medical students. And sometimes I would make quirky drawings just to help me remember the names of things Ive always preferred visual to verbal mnemonics. In this book, Ive set out to explore the human body as a miniature explorer, a Lilliputian embarking on a voyage, to retrace stories of discovery in human anatomy and to draw the landmarks that exist in the landscape of the body. Shrink yourself to a minute scale and the villi of the intestine look like looming, grassy mounds, while the islets of the pancreas look like stromatolites on a shore and the hollow space inside the upper jawbone looks like a dark, foreboding cavern. Some of my illustrations are more about the meanings of and inspirations for anatomical terms, or are just a bit weird because anatomy is weird, and wonderful.

Ive also tracked down the origin of terms, bringing out hidden messages and cultural allusions in the names, imagining the torn tendon of Achilles in an image on a black-figure vase, the Atlas vertebra holding up the world, and the duodenum as an alien creature with twelve fingers. Around 10 per cent of words in spoken English come from ancient Greek, while half are Latin, and the rest are Old English. Theres no hard and fast divide between these languages, though, as many Greek words entered Latin in antiquity and Germanic languages come from the same original source as the Romance languages a very ancient, Bronze Age tongue known as Proto-Indo-European. (We have no direct evidence of Proto-Indo-European or PIE, but linguists have reconstructed sounds and whole words based on similarities between spoken and historically attested Indo-European languages. The reconstructed words are always marked by a preceding asterisk). Through time, there would have been many words shared, stolen and borrowed between different languages. Even so, medical terminology is quite different from colloquial English. It is much more Greek as this was the scholarly language of antiquity; around two thirds of words in medical terminology are essentially Greek passed through a Latin filter sometimes via Arabic. This means that some words have become distracted from their original meaning, lost in translation. (The ancient Greek anatomist Herophilus almost certainly never thought that the large veins inside the skull bore any resemblance to a wine press, as we shall discover). But it also means that we might learn something important about a certain anatomical structure, and what its discoverers or namers thought of it, if we can dig back into that history of words, into their etymologies.)

The word etymology itself has an interesting etymology. It comes from Greek: logos, meaning study, and etymon, meaning truth. Its been used in the sense of true word since at least the sixteenth century and carries with it an idea that the origin of a word may reveal its true meaning. Of course, words and their meanings change through time, and with scientific terminology in particular, we are always primarily concerned with precise and current definitions when we write academic papers and medical reports. But the etymology of scientific terms does reveal a kind of truth it shows us what the early anatomists were focusing on when they thought up these names. It can make us think and look again at a particular piece of anatomy. It can also help us to remember the words.

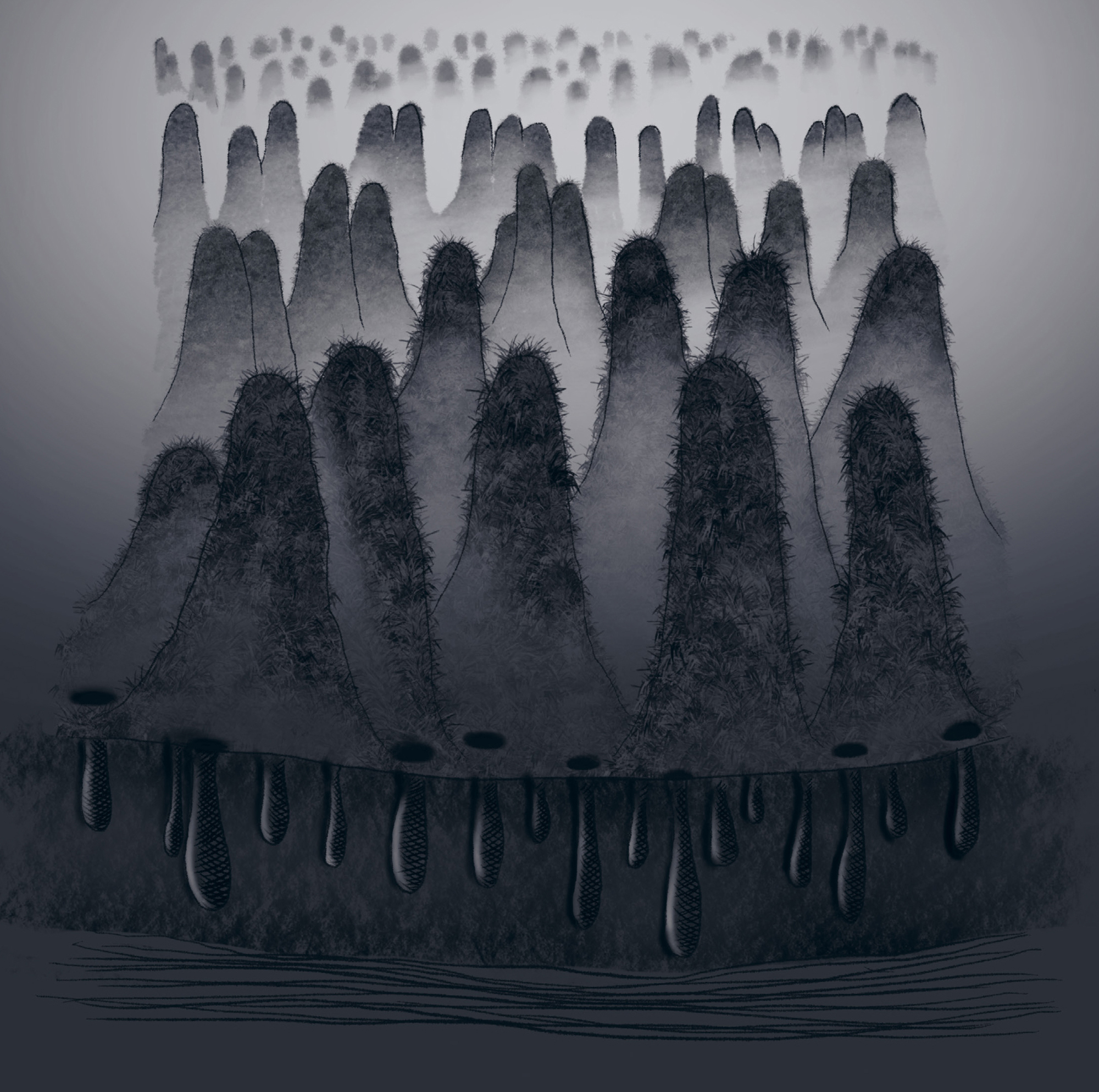

CRYPTS OF LIEBERKHN

I wanted to see my insides. I swallowed a large pill, gulping it down with water, and waited for the results. It was a pill-cam, and it provided me with a strangely intimate and revealing experience, beaming pictures of my intestines out of the dark recesses of my body onto a glowing screen. The pill-cam kept track of its path, too, and so I learned that my duodenum loops in a different way from most peoples an anatomical oddity that I had no idea about, and which doesnt signify anything beyond the fact that were all a little bit different, outside and in. Theres no single ideal, no peak of normal, just a spread of variation. Even if your duodenum doesnt twist like mine, the lining of your intestine would look similar, if you were to swallow a camera to see it. Lit by a tiny flash, the pill-cam revealed the pink lining of my duodenum, jejunum and ileum, and although the resolution wasnt all that high, there was the impression of fluffiness, like velvet or perhaps a shag-pile carpet. And thats because the surface is entirely covered in minute filaments. Theyre called villi, from the Latin for shaggy hair, which is very apt.

If you were able to zoom in closer still, youd see an epic landscape those shaggy filaments looking more like tall mounds, and each of these being shaggy too. The villi are covered with microvilli. And down around their bases youd see the dark openings of deep pits: well-like intestinal crypts. Everything is here for a reason. The shaggy villi with their shaggy microvilli increase the surface area of the intestine important for absorbing as much as you can from the digested contents of your guts. The deep wells are lined with cells which busy themselves making a cocktail of hormones, chemical signals to control digestion, and antibacterial fluid to eliminate unfriendly bacteria that happen to have wandered into you this far. The word crypt is perhaps more familiar from churches or tombs, where it describes an underground chamber. It comes from Greek, via Latin