Cover copyright 2018 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

Certain names and descriptions have been changed and some events combined or reordered.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Hachette Books is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Hachette Books name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

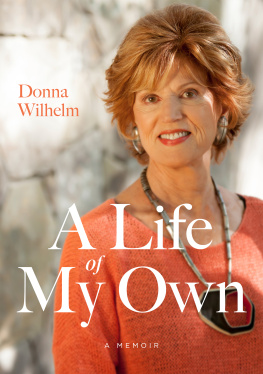

I have known Donna for over a decade. I knew her inside prison and I know her as a free woman. I know her more deeply than I have known many people, as I had the honor and privilege to travel with her in our writing group at Bedford Hills Correctional Facility for many years as she mined the depths of her own history, excavated the abuse done to her, and reckoned with her anger, shame, self-hatred, and guilt. I had a front-row seat witnessing Donna face her crime and probe her role and take responsibility and find the connections to her own trauma and history.

Now she has written a powerful and important book. It is a book that has arrived exactly at the moment it is needed. It is a book that has arrived as millions of women in America purge their stories and pain and memories and body traumas, and men reckon with their deeds and sexual misconduct. It has arrived at a moment of cultural excavation and hopefully a cultural transformation.

Donnas story shows with clarity and heart and painful personal detail the tragic trajectory of sexual violence. One has to ask about most women who have been sexually abused: At what point did they vacate their bodies and their lives? Was it the moment of the first violation? The second? In Donnas case, it is clear that she was long gone by the time the recurring acts of violence against her began.

Sexual violence forces us out of our bodies and ourselves. It lays us vulnerable to be controlled and further abused as our agency is stolen from the onset. It robs us of our sense of goodness; and once that is taken, so is our confidence and vision of a future. I know in my own case I became the darkness that was injected inside me. And then I lived in darkness for many years.

The time I spent at Bedford Hills, listening to stories, witnessing the layers of violence and violations women have suffered, made me aware that our prisons are filled with women who have been hurt and broken and abandoned. The statistics are shocking.

The overwhelming majority of women in prison are survivors of domestic violence. Three quarters of them have histories of severe physical abuse by an intimate partner during adulthood, and 82 percent suffered serious physical or sexual abuse as children. Nearly 8 in 10 female mentally ill inmates reported physical or sexual abuse. And 57.2 percent of females report abuse before their admission to state prison. Nearly 6 in 10 women in state prisons had experienced physical or sexual abuse in the past, and 69 percent reported that the assault occurred before age 18.

We have constructed a system that extols punishment over care and transformation, that categorically refuses to look at the economic, racial, psychological, or emotional roots of violence and forever perpetuates this violence through further institutional abuse.

The heartbreaking thing is that so many women woefully acknowledge that prison is the first place they ever felt safe, ever had time to think. So many women in my writing group at Bedford Hills came to realize in the course of our exploration how little choice they ever felt they had in their lives. Things just happened. The wheels of pain, exploitation, and violation moved them, and they never had a sense they could direct their own lives. And the wheels were set in dangerous motion from the first moment they were invaded, raped, beaten, tortured, or discarded. Because they were alone, without interventions or protections, they were propelled unwittingly toward a catastrophic cliff.

Donna was used and abused and abandoned from an early age. She had little control over her destiny or her even choosing her own family. She was spit out into the world as so many people continued to have their way with her. She lived in a state of perpetual terror, confusion, and powerlessness.

This book is a call for deep examination. It begs us to look at young womenparticularly those on the margins who remain invisible, where terrible things happen over and over. Donna was a brilliant, beautiful young woman. Her beauty was used against her time and time again. She was never allowed or encouraged to fulfill her intellectual prowess as her self-esteem and sense of goodness had already been demolished.

Donnas story highlights the fact that when the abuse of women in prison is treated and addressed, when inmates are able to tell their stories and explore what led them to prison, when they are given time and support to take responsibility for their crimes, they not only change but can become the most productive members of society.

My hope for Donna and her book is that it will be our wake-up call. Through reading A Little Piece of Light we will understand that Donnas story is the story of thousands of women, if not millions, who were ravaged before they had a chance to be born, who were propelled toward violence or violent situations by the incessant violence done to them.

We have a choice as a country. We can keep the industrial punishment machine alive, continue to demean, dehumanize, and hurt the most wounded. We can guarantee that they never find a way out of the maze of darkness. Or as Donnas story so brilliantly illustrates, we can offer attention, time, and care before and after that catastrophic moment occurs in womens lives.

Eve Ensler

Say his name.

I stand in front of the stainless-steel mirror in my cell in the solitary housing unit. My face is bare of any makeupthere is nothing covering this up, no making it any prettier. This is me, facing myself. Facing what I did. Say his name, I whisper at the mirror. SAY HIS NAME!

I brace myself to sit on the slab of metal that serves as my bed in my cell. Thomas Vigliarolo, I whimper. His name is Thomas Vigliarolo! The crescendo of sobs breaks me. Im sorry, Mr. V! I call out. Weak from the years of carrying this weight, my voice drops again to a whisper as I beg for his forgiveness. I am so sorry, Mr. V. I am so, so sorry that I didnt help you.

Cries echo throughout the unitmy own, and the cries of the women around me. In this place, our cries are our only release. We cry for ourselves, and we cry for each other. With each other.

For many of us here, imprisonment began long before the day we registered in prison. Feeling trapped and isolated began years before we found ourselves confined to a six-by-eight cinder block room with no clock to mark the time. A prison worse than any government facility is the feeling that nobody loves you. Nobody wants you. You belong nowhere. As the men in my life told me from the time I was a child: