Published by American Palate

A Division of The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2015 by Karen Dybis

All rights reserved

First published 2015

e-book edition 2015

ISBN 978.1.62585.522.0

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015942276

print edition ISBN 978.1.62619.985.9

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

To my family. To the people who make potato chips.

And to Detroiters near and far who love them.

Acknowledgements

Pray for peace and spiritual food, for wisdom and guidance, for all these are good, but dont forget the potatoes.

John Tyler Pettee

Some conversations stick in your head long after youve had them. One such moment happened when I interviewed Nick Nicolay, president of Kars Nuts in Madison Heights, Michigan. Mr. Nicolay told me about his grandfather and his potato chip company called New Era. He mentioned that there once were dozens of chippers in Detroit, and I was astounded. My curiosity and subsequent research about these companies led to this project. I offer many thanks to Nick for sharing his familys story and snack food legacy.

Special thanks go to Better Made Snack Foods, as well as to the families of Cross Moceri and Pete Cipriano. I appreciate your willingness to come on board when I suggested this book. Having your personal photos and recollections took this seed of a story about the industrys early years into the modern era. Thank you to Better Mades executive team, especially Mark Winkelman, Mark Costello and Mike Esseltine, for your help and trust throughout this project. Thanks to company publicist Franklin Dohanyos for telling me about National Potato Chip Day and securing my first Better Made interview. Thank you to the companys longtime employees, especially George Orris, Phil Amigoni and Russ Leone, for putting up with endless questions about what it was like to work for Detroits first chippers. Your priceless photos helped me imagine just how heavy those bags of potatoes must have been.

Thank you to Betty Dancey Godard for your incredible memories about your father, Russell V. Dancey, and his partner, Ernest Nicolay, at New Era Potato Chip Company. Your stories about Best Maid and New Era were among my favoritesthey provided the best historical gossip of my journalistic career.

Thank you to Dirk Burhans for your insights on the potato chip industry. Your book, Crunch!, never left my side during this process, and I appreciate how much work you put into its creation.

Thank you to the Detroit Drunken Historical Society and its members for their insights, which resulted in many new finds for this book. Thanks to Rachel Lutz, whose clever mind created the term chipreneurs, which is scattered throughout this work. I also have endless gratitude to friendsincluding Jessica Killenberg-Muzik, Blayne Brocker, Susie Thibault, LeeAnn Jurczyk, Phil Olter and many otherswho answered my pleas for help with photos of chip-loving Better Made fans.

A final and important thank you goes to my family. You were willing taste-testers and rough draft reviewers. I appreciate your patience as I worked through this salty story.

Prologue

Oil, Salt and Potatoes

Potato chipsthose salty, golden morsels that are the definition of American ingenuityare a deceptively simple snack food.

The average potato chip bag lists three ingredients: oil, salt and potatoes. That humble tuber mixed with a handful of spice and fried at the right temperature becomes something akin to magic. They not only fill peoples bellies but also put a smile on their collective faces.

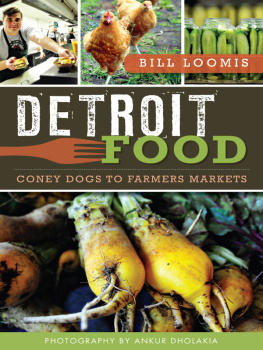

For Detroit and many cities like it, potato chips provided that and so much more: jobs, name recognition and a taste that came to define home. With just three ingredients, home-based potato chip manufacturers sprang up across Detroit in the 1920s. These early chippers created a cottage industry in a bustling metropolis with a reputation for fast cars and hungry entrepreneurs.

The humble goal of earning a little pocket money expanded in the 1930s. A few dozen companies grew into commercial kitchens, where the owners friends, neighbors and, in many cases, Detroits increasing immigrant population worked with dexterity to fill bags with chips and staple them shut. Door-to-door hustle combined with stands in hot spots like Belle Isle also fed these fledging businesses.

By the 1940s, small kettle-cooked batches had given way to industrial fryers. Paper or wax bags were replaced with foil-lined versions that were machine sealed. The days of carrying bags of potatoes in from the truck waned as conveyor belts replaced young muscle. Women of all ageswhether they were high school graduates, single mothers or widowsworked the factory floor and in a growing number of storefronts. Men took care of the frying, worked in the warehouses and delivered the finished product to the neighborhood grocers, druggists and convenience stores across the city.

A few companies transformed again into factories whose busy production lines defined the Nifty Fifties, giving livelihoods to those men and women who needed jobs after World War II. A handful of businesses had exploded into conglomerates by the swinging 60s, establishing brands whose manufacturing might and deep distribution channels allowed them to gain dominance over the states snack food industry.

As the decades passed, many beloved household names would go from family businesses to corporate ownership. By the 1980s, mergers, the race toward automation and competition for shelf space had driven most Detroit chippers out of existence. Their only legacy was rusted tins inside the family attic or faded advertisements painted on silos along Michigans blue highways.

The longest-lasting company to survive those ups, downs and everything in between is Better Made Snack Foods. Its plant on Detroits Gratiot Avenue is a landmark in this hard-luck city. People of all ages recognize its logo, which features a friendly young maid whose product is Guest Qualitythat is, fine enough to serve anyone who might grace your doorstep.

Two distant cousinsPete Cipriano and Cross Moceristarted Better Made with a single truck and a few hundred dollars in cash. They had a mutual devotion to excellence, personally supervising production to ensure that chips were crispy, delicate and perfect. With its impeccably fried products, Better Made set the standard among other companies. Everyone judged their chips by Better Mades color, its freshness and, most importantly, its taste.

The fact that Better Made endured from its incorporation in 1930 to today is a bit of a miracle in and of itself. Better Made fought a plethora of challenges from national potato chip companies to fickle consumers to Detroits population woes. Its owners clashed on key aspects of the business, creating such heated debates that Cipriano would walk out of the room if Moceri came in and vice versa. When the two families finally separated through a buyout in 2003, there was a moment when it looked like the company might have reached its end.

Next page