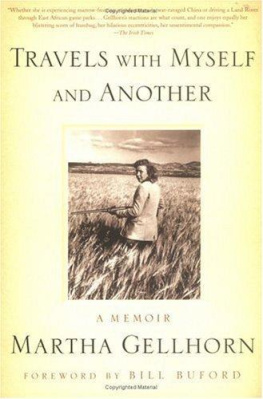

Copyright 1988 and in the original year of publication for each piece by Martha Gellhorn

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Any members of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or publishers who would like to obtain permission to include the work in an anthology, should send their inquiries to Grove/Atlantic, Inc., 841 Broadway, New York, NY 10003.

Published simultaneously in Canada

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gellhorn, Martha, 19081998

The view from the ground.

I. Title.

PS3513.E46V54 1987814.5287-31837

ISBN 0-87113-212-5

eISBN: 978-0-8021-9117-5

Cover photograph by Ian Berry

Design by Laura Hammond Hough

Atlantic Monthly Press

841 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

99 00 01 02 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2

Author's Note

This book is a selection of articles written during five decades; peace-time reporting. That is to say, the countries in the back-ground were at peace at the moment of writing; not that there was peace on earth. The articles are reprinted as originally published (warts and all) in chronological order by date of publication except as follows: the time of the event in the first article, Justice at Night, 1931, places it, not the later date of publication. The second, My Dear Mr. Hopkins, is not an article but a compilation of reports. In the seventies, Beautiful Day of Dissent failed to find a publisher, and When Franco Died was published by New york magazine and The Observer (London) and both cut it for space, differently. Having lost the original copy, I pieced the two together to make what I hope is the whole. The translation of the testimony in On Torture has been expanded. I have changed tides which were not my choice.

I decided to put my hindsight comments on the decades at the end of each period, leaving the reader alone with the articles before I intruded with explanations.

Justice at Night

THE SPECTATOR , August 1936

We got off the day coach at Trenton, New Jersey, and bought a car for $28.50. It was an eight year old Dodge open touring-car and the back seat was full of fallen leaves. A boy, who worked for the car dealer, drove us to the City Hall to get an automobile license and he said: The boss gypped the pants off you, you should of got this machine for $20 flat and it's not worth that. So we started out to tour across America, which is, roughly speaking, a distance of 3,000 miles.

I have to tell this because without the car, and without the peculiarly weak insides of that car, we should not have seen a lynching.

It was September, and as we drove south the days were dusty and hot and the sky was pale. We skidded in dust that was as moving and uncertain as sand, and when we stopped for the night we scraped it off our faces and shook it from our hair like powder. So, finally, we thought we'd drive at night, which would be cooler anyhow, and we wouldn't see the dust coming at us. The beauty of America is its desolation: once you leave New England and the industrial centers of the east you feel that no one lives in the country at all. In the south you see a few people, stationary in the fields, thinking or just standing, and broken shacks where people more or less live, thin people who are accustomed to semi-starvation and crops that never quite pay enough. The towns or villages give an impression of belonging to the flies; and it is impossible to imagine that on occasion these languid people move with a furious purpose.

We drove through Mississippi at night, trying to get to a town called Columbia, hoping that the hotel would be less slovenly than usual and that there would be some food available. The car broke down. We did everything we could think of doing, which wasn't much, and once or twice it panted wearily and then there was silence. We sat in it and cursed and wondered what to do. No one passed; there was no reason for anyone to pass. The roads are bad and mosquitoes sing too close the minute you stop moving. And the only reason to go to a small town in Mississippi is to sell something, or try to sell, and that doesn't happen late at night.

It was thirty miles or more to Columbia and we were tired. If it hadn't been for the mosquitoes we should simply have slept in the car and hoped that someone would drive past in the morning. As it was we smoked cigarettes and swatted at ourselves and swore and hated machinery and talked about the good old days when people got about in stage-coaches. It didn't make things better and we had fallen into a helpless silence when we heard a car coming. From some distance we could hear it banging over the ruts in the road. We climbed out and stood so the headlights would find us and presently a truck appeared, swaying crazily. It stopped and a man leaned out. As a matter of fact, he sagged out the side and he had a bottle in one hand, waving it at us.

Anything wrong? he said.

We explained about the car and asked for a lift. He pulled his head into the truck and consulted with the driver. Then he reappeared and said they'd give us a lift to Columbia later, but first they were going to a lynching and if we didn't mind the detour....

We climbed into the truck.

Northerners? the driver said. Where did you all come from?

We said that we had driven down from Trenton in New Jersey and he said, In that old piece of tin? referring to our car. The other man wiped the neck of the bottle by running his finger around inside it, and offered it to me. Do you good, he said, best corn outside Kentucky. It was no time to refuse hospitality. I drank some of the stuff which had a taste like gasoline, except that it was like gasoline on fire, and he handed it to my friend Joe, who also drank some and coughed, and they both laughed.

I said timidly, Who's getting lynched?

Some goddam nigger, name of Hyacinth as I recollect.

What did he do?

He got after a white woman. I began to think with doubt and disgust of this explanation. So I asked who the woman was.