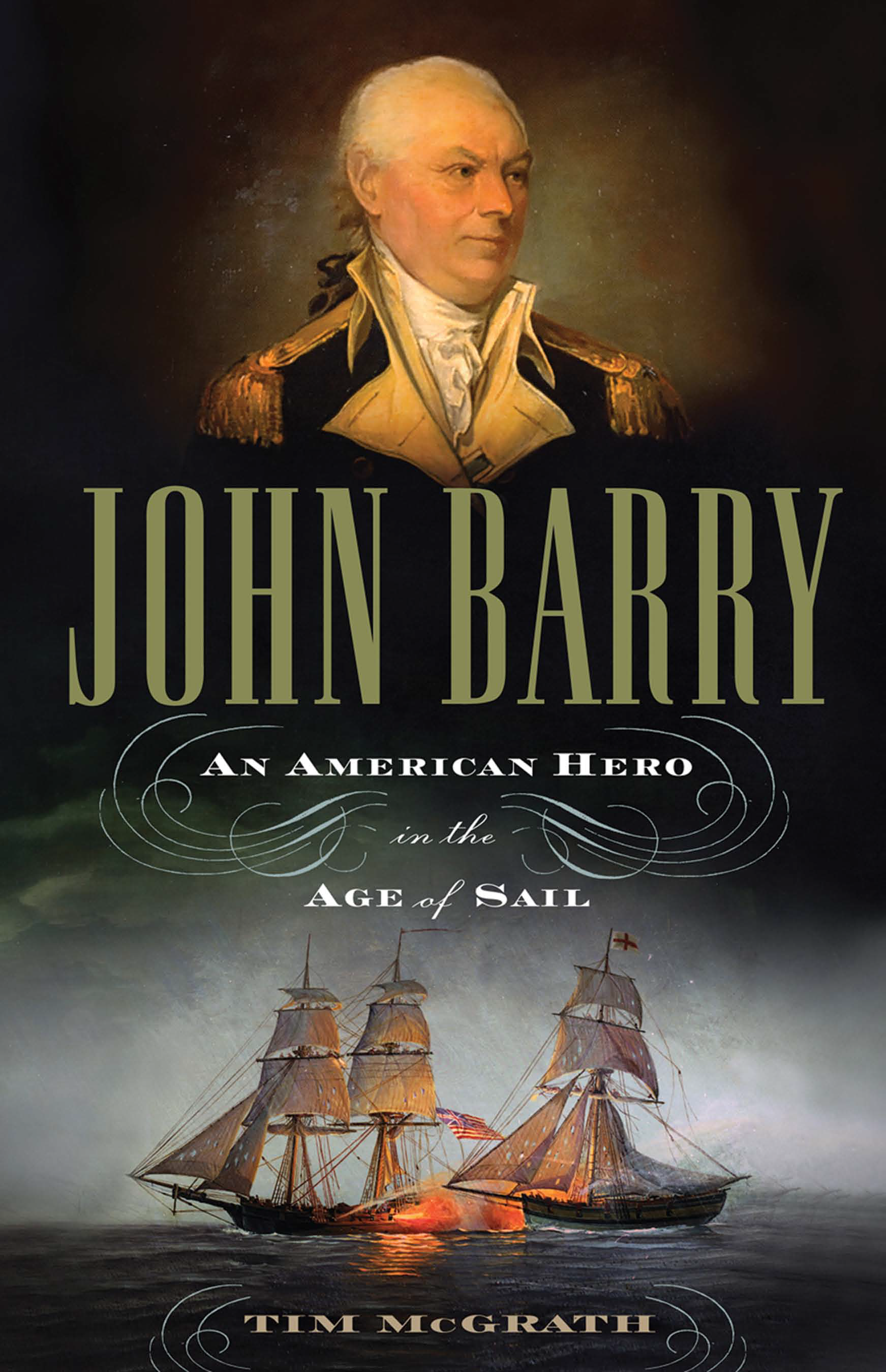

Frontispiece: Portrait of John Barry by Gilbert Stuart, c. 1801. (Bruce Gimelson Gallery/Private Collection)

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Produced in United States of America.

FOREWORD

THE STATUE STANDS TALL AND RESOLUTE, with a defiant expression on his face. His left hand holds a spyglass above a sheathed sword. His right arm points southward over Philadelphia: the same direction that the Delaware River takes toward the sea. To some who know the lay of old Philadelphiaand the location of St. Mary's cemeteryhis gesture seems to say, I'm buried over there. He has been guarding the south side of Independence Hall for a hundred years.

He paid no attention to the rain falling on September 13, 2003, as a hundred or so people made their way from his gravesite at St. Mary's churchyard at Fourth and Locust, working their way toward him under a colorful collection of umbrellas. They had just attended a ceremonial Mass and a simple, martial service at his resting place, commemorating the two hundredth anniversary of his death. They were led by an honor guard comprised of sailors from today's United States Navy and re-enactors dressed as Revolutionary War soldiers, marching in cadence as bagpipes played. They reached the statue and the pipes stopped playing (the rain kept falling); remarks were made by one priest, one admiral, and one mayor. The national anthem was sung, a benediction given, and the spectators left the statue to gather for lunch at the nearby Curtis Building.

After the meal, the vice consul of Ireland made a brief speech, and a plaque was presented by members of the crew from the latest U.S. destroyer that carries the same name as the statue. Descendants, veterans, and members of the various Irish and civic organizations that had sponsored the event toured an exhibit of artifacts, weapons, and paintings from the early days of the United States. Eventually everyone drifted out into the rain, and back to the twenty-first century. Outside, it continued to rain on the statue's hat, his outstretched arm, his spyglass, his buckled shoes, and the pedestal that bears his name: Barry.

A century earlier, when the statue was unveiled, thousands attended, and the event was front-page headlines in the newspapers of the day.

Philadelphia has two statues and a nearby bridge named after John Barry. There are other statues, in Washington, D.C., and in Ireland's County Wexford, where he was born. There are countless Commodore Barry Chapters of the Friendly Sons of St. Patrick and the Ancient Order of Hibernians. But as time passes, John Barry is being forgotten.

Barry is still called Father of the American Navy in some circles, although John Paul Jones and John Adams are two others that can lay claim to that title. But where Adams has eternal fame from being second President of the United States, and Jones still has not yet begun to fight in some high school history books, few can recall Barry's deeds. Two hundred years ago, it was a different story.

The fastest known twenty-four hours logged at sea in the eighteenth century? The Black Prince, captained by John Barry. The first and last successful battles fought at sea for the Continental Navy? Captain Barry. The fighting sailor who served with the Continental Army at Princeton? Barry. The veteran who seized the moment (and a couple of state assemblymen) to guarantee a quorum for Pennsylvania's ratification of the Constitution? None other. The merchant captain who helped establish trade with China and the man President Washington put at the top of the list to head up the United States Navy? The very same.

Why don't we know more about this man?

For one thing, he was not pompous. Take, for example, his desperate passage down the Delaware past occupied Philadelphia in 1778. It was a freezing winter night when he led forty threadbare and poorly armed sailors silently past British warships and helped conduct a legal rustling party with Anthony Wayne. The cattle they rounded up fed the starving soldiers at Valley Forge. John Paul Jones, always his own best press agent, would have written a poem describing his heroic exploits, full of bravado. Barry wrote, I passed Philadelphia in two small boats. Other documents, personal and public, show his affection, anger, humor, and purpose. But they pale in comparison to the writings of his peers, many of whom wrote volumes more and accomplished much, much less. No wonder the historians at the Washington Navy Yard affectionately call him Silent John.

His early time in Ireland left no paper trail. Irish and American historians once debated about where and when he was born. Was it in Ballysampson? Or Roostontown? Or Rosslare? Was it in 1739? Or 1745? The records are, as Celestine Rafferty (the Barry expert in Wexford) says, A tad sketchy.

His youth is practically undocumented. For his first six years in Philadelphia, we don't know where he lived or whom he worked for. He married Mary Cleary, but her name is all we know about her. Tax records of 1767 list his household with their names and a servant. Was this servant indentured or a slave? We don't know. During the British occupation of Philadelphia he was approached by a British sympathizer and offered a commission in the King's Navy along with 15,000 guineas. No documents from the Clinton or Howe papers mention who the go-between was, and Barry never told. Silent John. But most of those who knew himGeorge Washington, Robert Morris, even John Paul Jonestendered him their respect and admiration.

Visit that statue on a bright sunny day, as the tourists leave Independence Hall and walk by. The cameras will come out, families will pose, and a stranger will offer to take a picture of all of them. Invariably one sightseer will look at the name and ask, Who was Barry?

Here are his times. This is his story.

CHAPTER ONE

OUT OF IRELAND

THE LAST THING AN ACTING COMMANDER needs is flagrant disobedience to orders. Lieutenant Stephen Gregory was well aware of that fact as he stood on the quarterdeck of the Continental frigate Confederacy; his crew intently watched him struggle to maintain both his poise and authority.

Although the 1779 calendar read Octoberusually a brisk month for Pennsylvaniathis had been a pleasant, agreeably warm morning, with southerly breezes wafting up the Delaware River. For Gregory, it had been pleasant and agreeable enough, until this defiant brig sailed within hailing distance. Every other passing ship obeyed Gregory's commands to turn into the wind and be boarded, but this brig's captain showed no intention of doing so.