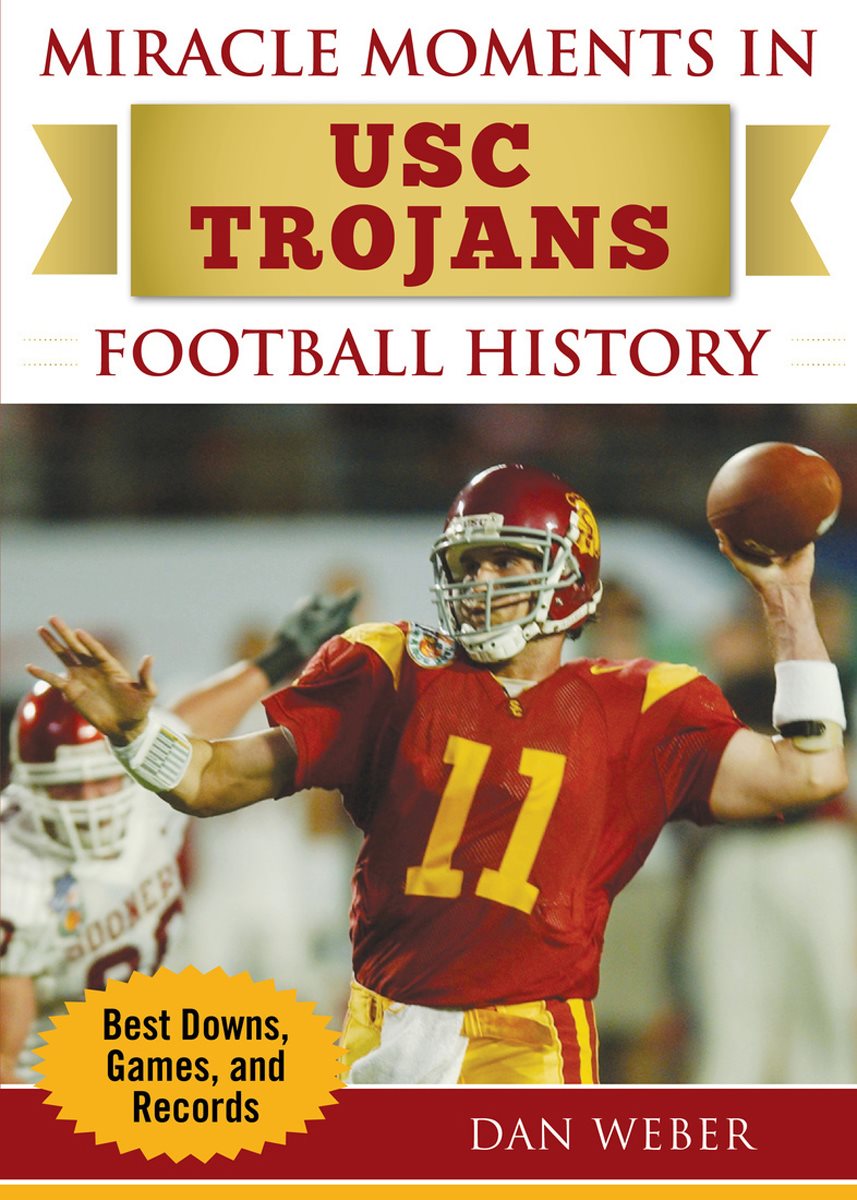

Copyright 2018 by Dan Weber

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Sports Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Sports Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Sports Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Sports Publishing is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.sportspubbooks.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Cover design by Tom Lau

Cover photo credit AP Images

Interior photos by Long Photography, Kathe Osborne, Dan Avila, Sam Hawthorne, Kirby Lee, and John McGillen (courtesy of USCs Sports Information Department), except where noted.

ISBN: 978-1-68358-246-5

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-68358-247-2

Printed in China

Contents

INTRODUCTION

Its a storyor many of themworthy of Hollywood. The miracle moments that USC football history has produced would easily provide the plot lines for all sorts of big-screen extravaganza treatment.

And theyre all true. No one has to make them up.

Here are a number that tell of the people who breathed life into USC football, who took it to the top, who set the standards, who won national championships and Heisman Trophies and Rose Bowls and the hearts of the fans of a growing Southern California just ready to burst into Americas cultural consciousness from the booming 1920s on.

USC football was right there every step of the way: from matchups against the Thundering Herd to two separate Wild Bunches (1969 and 2003), from Antelope Al to Jaguar Jon, from Iron Mike to Prince Hal, from Cotton to Thunder & Lightning, Trojans football has been on the tip of the tongue for SoCal fans and beyond. Ironically, the lone program in college football history never to have put the players names on the backs of their jerseys because its all about the team would produce so many whose names we all can recall.

But it wouldnt do so right away. The team they were calling the Methodists or the Wesleyans played its first football game in 1888, after Professor Elmer Merrill suggested to Henry Goddard, USCs first coach who had played football himself in college, that they teach these boys some football. It was 19 years after Rutgers and Princeton had played the first college football game in 1869 that the sport reached Los Angeles.

Yet it was hardly special. At the turn of the century, for just one example, USC was shut out the first five times it faced the Sherman Indian Institute from nearby Riverside by a total score of 720 in four losses and a scoreless tie. And when it went in search of a new nickname in 1912, asking the Los Angeles Times sports editor Owen Bird for help, he gave it to them. He came up with Trojans, he said, with an explanation for USCs competitive issues at the time.

The athletes and coaches of the university were under terrific handicaps, the USC football media guide quotes Birds reasoning. They were facing teams that were bigger and better equipped, yet they had splendid fighting spirit. The name Trojans fitted them.

It certainly fit USCs first All-American, lineman Brice Taylor, one of college footballs few African-Americans to earn such honors in the games first eight decades. An orphan adopted by Italian-Americans and a descendant of the great Indian chief Tecumseh, the Seattle native overcame one other hurdle. He was born without a left hand, limiting the speedy athlete to playing on the line. But a lineman fast enough to run on USCs world-record 400-meter relay team had certain advantages, as Taylor served as a transition to what was to come next for USC football.

USC had been no match for a national powerhouse on the West Coast like Cal, a team USC beat just once in their first ten meetings. And then the world turned. Within a years time in 1922 and 1923, the incredibly optimistic citizens of Pasadena and then Los Angeles built a pair of the worlds iconic sporting venues geared to footballthe Rose Bowl and the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum.

Imagine that. With a population of no more than 550,000 in the mid-1920s, Greater LA would have two new stadiums that would ultimately seat 100,000 each; one would host the bowl game that became the Grand-Daddy of them all, and the other venue will soon become (in 2028) the first ever to host three Summer Olympics, not to mention twelve national champion football teams, including a Trojans team that would dominate the Rose Bowl, plus a place where they play a World Series and host two NFL teams, a president, and a Pope.

With one of the worlds great stadiums just across the street from its campus, USC would get on board and, buying out Coach Elmer Gloomy Gus Henderson and after a 920 season and failing to lure Knute Rockne from Notre Dame, would do the next best thing and entice Hall of Famer Howard Jones. An All-American and one-time coach at Yale, Jones headed west from Iowa at Rocknes suggestion. That move would change college football on the West Coast and in the nation forever.

Not only would the Trojans soon be dispatching Cal and Stanford, they would install Notre Dame and Rockne as a schedule fixture, a move that solidified both programs in the firmament of college football, especially when the likes of Michigan and Ohio State were shunning private school Notre Dame. The nation responded. The first two times USC and Notre Dame met in 1927 and 1929, 120,000 turned out for the first game, 112,912 for the second. Both LA games drew capacity crowds of more than 72,000 at the Coliseum.

But college footballs greatest intersectional series would do more than draw fans: it would set up the two teams as the measure for college football excellence, as no one but USC (in 1928, 1931, and 1932) and Notre Dame (in 1929 and 1930in Rocknes last game) would win a national championship for those five straight seasons. A decade later, USC would be facing a similar situation with the loss of Jones, to a heart attack, after the 1940 season and his teams four national championships and a perfect 50 record in the Rose Bowl.

Getting back to the Howard Jones Era would not come easily. There were occasional highlights, like the day in 1956 when USC running back C.R. Roberts would not only help desegregate Austin, Texas, and the Southwest Conference, but hed put up a record-breaking day in a win over the Longhorns.

Still, twenty-three middling seasons would go by before a young son of a tiny West Virginia coal town would show USC the way. John McKay had put in his WWII service as a B-29 tail-gunner and physical instructor, then returned to play football at Purdue and Oregon, where as an assistant coach, he attracted the Trojans interest. But it took some luck for the wise-cracking, cigar-smoking McKay to survive into his third season after opening with a pair of losing seasons and an 8111 record.

But survive he did. And then in 1962, it happeneda national championship and a win in the most wide-open, action-packed Rose Bowl ever to that time, 4237, over Wisconsin. Another triumphant Trojans era had begun. By the time he would leave for Tampa Bay and the NFL in 1976, McKays Trojans won four national titles, just like Jones, along with five Rose Bowl wins in eight tries.

Next page