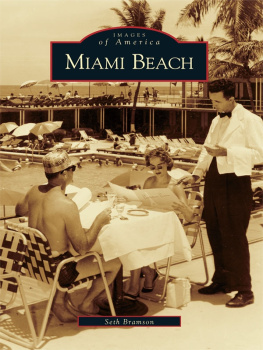

IMAGES

of America

ORGANIZED CRIME

IN MIAMI

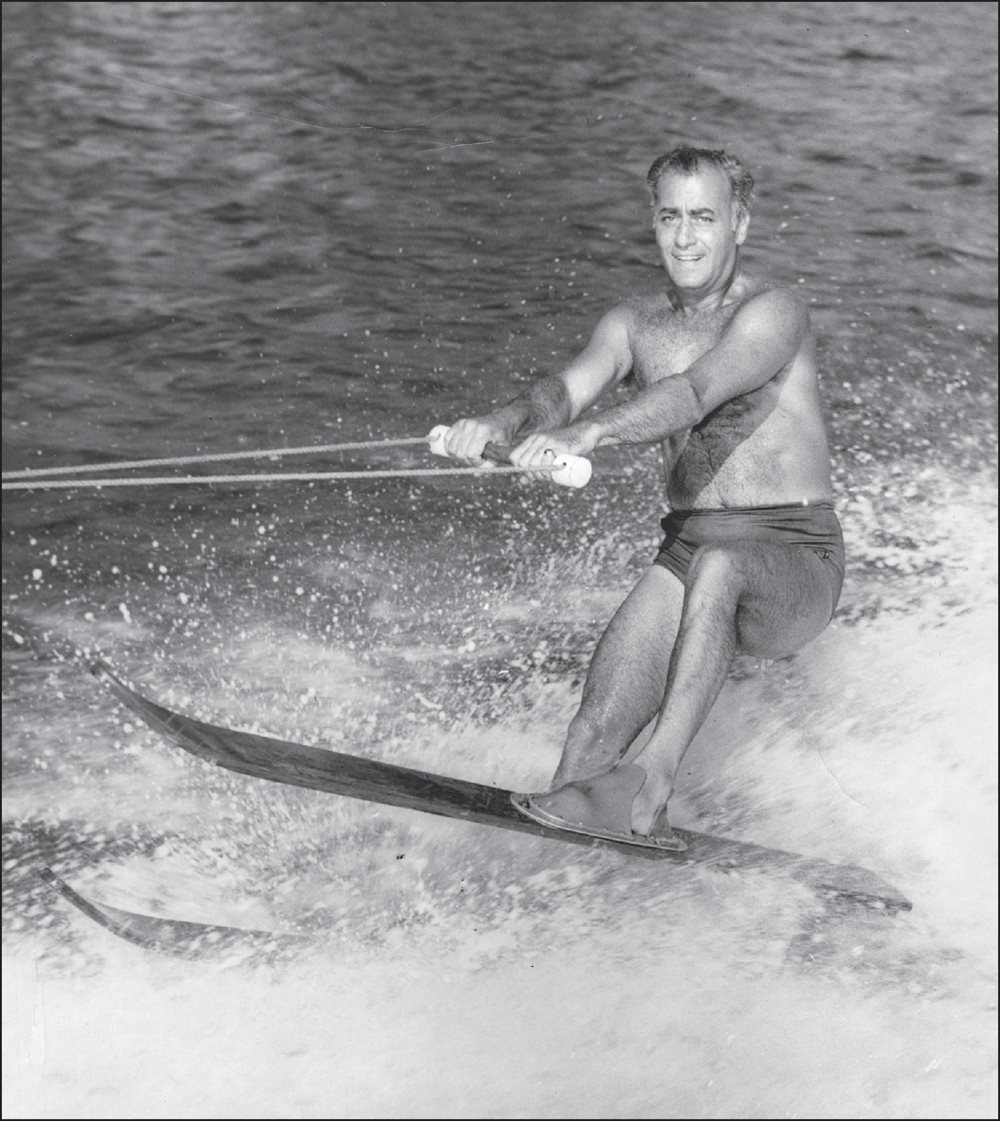

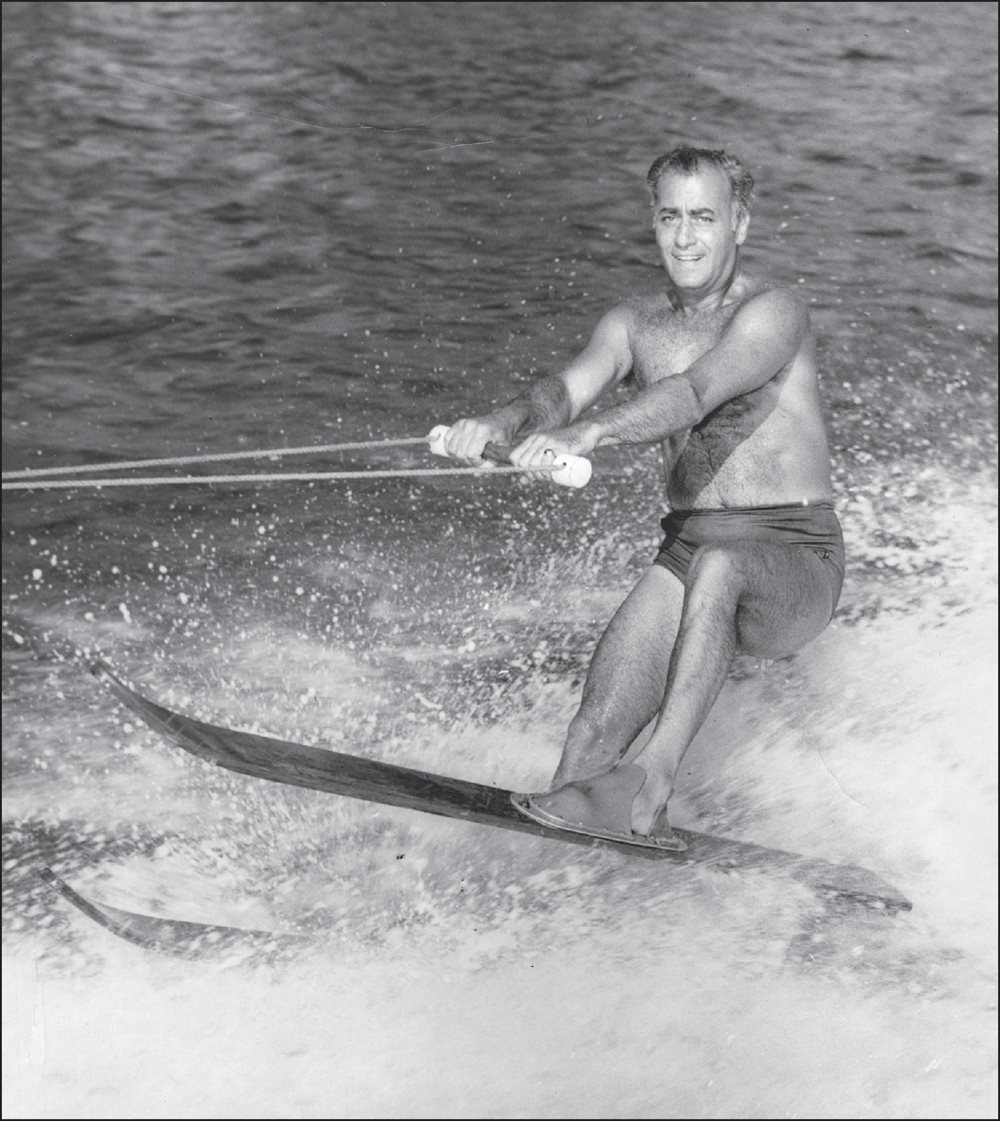

Joseph Fischetti, brother of notorious Chicago mobsters Charlie and Rocco Fischetti, confidently poses while waterskiing in Miami Beach. Operating from the Magic City, Joe maintained substantial connections to major crime figures around the country, as well as a close friendship with Frank Sinatra, which the gangster parlayed into lucrative business deals throughout South Florida. Read all about the Fischetti family and their Miami exploits in the opening pages of , Swimming with the Fishes. (Authors collection.)

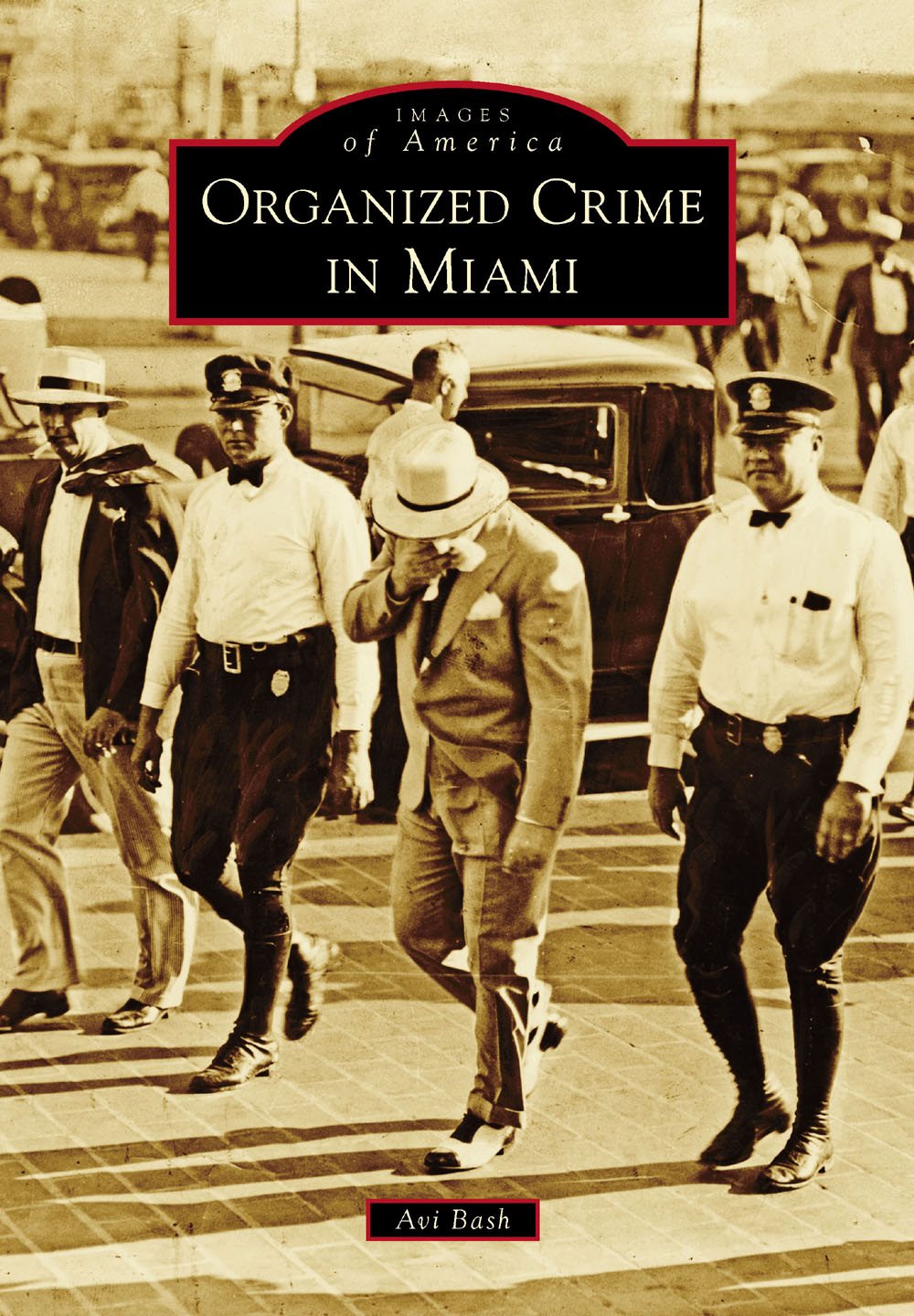

ON THE COVER: Arrested with three companions, Al Capone (center) hides his face as he and his cohorts are led to a downtown Miami police station. In May 1930, Miami police continually harassed Capone, with multiple arrests for investigation or vagrancy. Capones lawyers sued the city for harassment and false imprisonment; however, Capone would be charged with two counts of perjury for statements made in his harassment claims. After a three-day trial, Judge E.C. Collins acquitted Capone of the perjury charges. (HistoryMiami Museum, 1989-011-19510.)

IMAGES

of America

ORGANIZED CRIME

IN MIAMI

Avi Bash

Copyright 2016 by Avi Bash

ISBN 978-1-4671-2395-2

Ebook ISBN 9781439658840

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016935373

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

The author would like to dedicate this book to his father, Yossi, and the loving memory of his mother, Vicki.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to express my gratitude to those who have assisted throughout the process of this book, whether through contributions, support, insight, or feedback. This completed work would not have been possible without the following: Dawn Hugh, Kristen Kotowski, and Ashley Trujillo of the HistoryMiami Research Center; Gordon Winslow, Patty Pauzuolis, and Allison Hooper of the Miami-Dade Municipal Archives; the State Archives of Florida; Caitrin Cunningham and Katelyn Carter of Arcadia Publishing; John Binder; Marnix Brendel; Geoff Schumacher and the Mob Museum staff; Casey Piket; Scott Deitche; the estate of Thomas McGinty; the Estate of Nicholas Fischetti; Viki Varon Armstrong; Jim from Boston; Yossi and Whiskey Bash; Stacy, Travis, Layla, and Liam Gibb; Aaron and Pnina Sobel; David J. Berkowitz; Bryan Rubin; Jesse Stamler; and most important, the law enforcement, public officials, newspapermen, and photographers who tirelessly combated and exposed organized crime. Without their meticulously documented findings and reporting, none of this research would have been possible.

INTRODUCTION

At the time of the great Florida land boom of the 1920s, hundreds of thousands of Americans began flooding South Florida looking to start a new life in what developers audaciously referred to as a tropical paradise. The sudden influx of residents and tourists, along with rapidly developing city amenities, earned Miami its everlasting nickname, the Magic City. But as with any highly populated metropolitan area, Miami residents and their guests would seek an exciting, vice-filled nightlife to counterpoise the relaxing, calm afternoons lounging on Miamis white-sand beaches. These new Miami locals desired nightclubs, gambling, and most important, liquor, the latter of which happened to be illegal due to the recently ratified 19th amendment that banned the sale and consumption of said product. Mobsters from around the country who were happy to provide these illegal yet highly profitable illicit services found Miami to be the perfect refuge from law enforcement or rival gangs. Individuals from crime families spanning the nation were eager to volunteer their services and set up shop in the quickly budding Miami business market. It was at this time that the American mafia would begin heading south to trade in their suits and fedoras for swim trunks and flip-flops.

Despite the arrival of earlier national crime figures, the county first recognized Miami as a gangsters paradise when newspaper headlines broadcast the arrival of Chicago mob boss Al Capone and his intentions to plant roots in Miamis rich soil. By the 1930s, Prohibition was a thing of the past, and the Great Depression was ravaging the countrys economy. Knowing that financially stable Americans looking for an escape were traveling to South Florida, mobsters arrived in bulk and set up their largest enterprise, one that would provide an everlasting foot in Magic Citys doorillegal gambling.

In many aspects, Miami has always been an open city, and the same is true with respect to the mobs arrival and its subsequent impact on the citys development. Representatives from crime syndicates in New York, Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland, and other major metropolises worked harmoniously among each other with little conflict for the first half of the 20th century. These polished criminals understood that dividing territory, splitting operations, and sharing profits would keep internal crime down and, more important, draw little publicitya necessity for the continual success of their illegal operations. The swift growth of Miami Beach and its surrounding cities was also a welcomed phenomenon to the local law enforcement officers elected and entrusted to patrol the area. When worthless orange groves and mangrove swamps were wondrously transformed into casinos and nightclubs, local sheriffs and deputies ignored orders from state officials and eagerly accepted bribes to ensure that illegal casinos and bookie joints ran smoothly for their new favorite locals.

For more than two decades, gangsters flocking to Miami discovered that the Magic City was, in fact, magical. Besides the perfect year-round climate and enormous profits, Miami also provided convenient access to neighboring countries in which the mob held prosperous business interest. With a short trip by boat, or even shorter by plane, mobsters could easily access Cuba, the Bahamas, and other surrounding Caribbean islands where their gambling establishments were booming. Utilizing profits from their gambling enterprises, crime figures began to invest in real estate and legitimate businesses, further embedding their influence within the community and blurring the line between crook and honest businessmen.

By the mid-1940s, the American mafia had fully infiltrated Miami, with nearly all hotels allowing gambling and open wagering from bookie concessions conveniently located on the premises. Hotels like the Sands, Wofford, and Grand were owned and operated by known mobsters and quickly became local hangouts for visiting gangsters and associates. Seemingly overnight, organized crime figures began buying land, homes, and winter residences in Miamis most prominent neighborhoods, as well as donating to local charities and organizations, greatly contributing to the communitys tremendous development. As the 1950s rolled in, little seemed to be able to interrupt the flow of cash generated from the mobs various activitiesthat is, until Tennessee senator Estes Kefauver launched a campaign to investigate, expose, and eliminate illegal gambling in the United States. With television in its relative infancy, the heavily publicized Kefauver Committee hearings aired to a shocked nation, vividly bringing to life the existence of the mafia and the individuals controlling it. With the assistance of crusading public officials, Kefauver exposed South Floridians to the high level of corruption running rampant throughout their cities. Ritzy casinos were ordered shut, bookmakers whose identities were revealed in the local papers were forced from town, and gangsters from across the country understood that the Magic City had finally lost its magic.

Next page