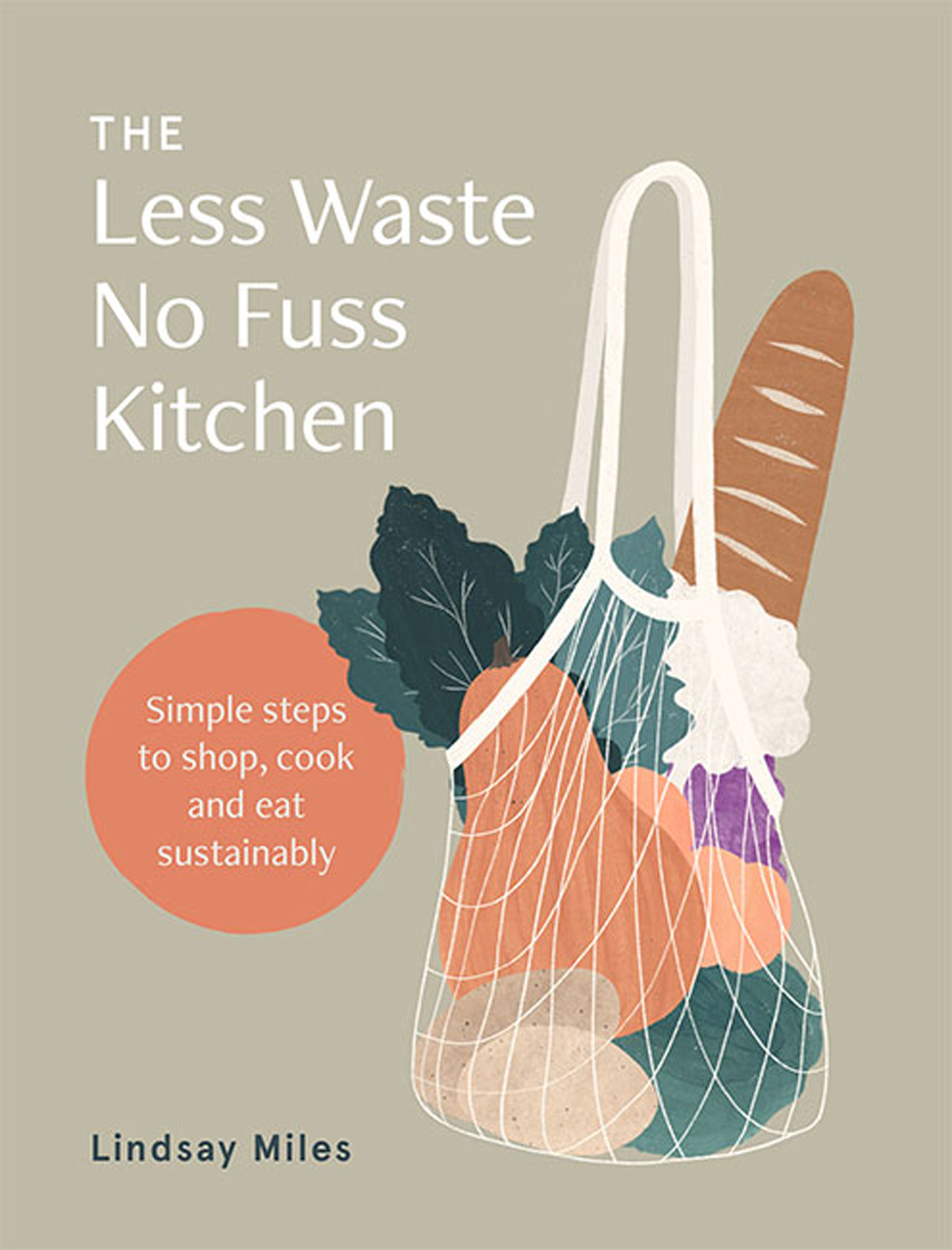

How do you go from being a supermarket-shopping, convenience-food-eating plastic addict who finds the idea of making things from scratch more than a little intimidating, to a mindful, seasonal(ish) eater who shops locally, eschews packaging (for the most part) and feels reasonably confident in the kitchen?

It doesnt happen overnight. But it can happen. Step by step, one switch at a time.

Your goal might not be a complete lifestyle makeover. But as youre here Im guessing that youre interested in trying to reduce your impact lowering your carbon footprint, avoiding excess packaging and minimising food waste. The most sustainable way to reduce your impact is in a way that works for you. I like to call it the no fuss approach.

The kitchen, as youre about to find out, is a great place to start when it comes to reducing your impact. There are so many things that are no longer sustainable with our current food system, but also so many opportunities to tweak our habits and make better buying decisions. Plus, everybody eats!

First, though, lets get one thing clear: there is no such thing as planetarily perfect. The closest thing that comes to my mind is somebody working the land, growing all their own food, saving all their seeds, preserving their entire harvest, capturing sun and wind energy, and composting everything (and no, I dont mean only the food scraps).

Do you know anyone who lives like this?

I didnt think so. Me neither.

This lifestyle just isnt realistic or practical (or desirable!) for the majority of us. And anything outside of it has some kind of footprint. So were going to drop this notion of 'perfect' altogether, and go for doing what we can.

Other people will have different priorities, and make different choices to us. Thats not to say these are better or worse; they are simply different choices for different circumstances.

Too often when we read about reducing our footprint, we come across should and should not statements. Not in this book. Its purpose is to give you the ideas and tools to make changes and feel positive about the things you can do, not guilty about those things you cant. And anyway, no one does all of the things, all of the time.

Instead, I want to help you understand the issues so you can choose what you want to do. Im here to help you navigate the complex and sometimes conflicting options when it comes to eating ethically and sustainably, support you in reducing your waste and lowering your footprint in a way that fits in with your lifestyle, and persuade you that spending a bit more time in the kitchen can be as fun (and delicious) as it is rewarding!

Planetarily perfect might not be a thing, but there is plenty of opportunity to have a positive impact through the food we buy, how we buy it, and what we do with it once we get it home. And when I say plenty, I mean every single day.

Our modern-day food system (and why its no longer sustainable)

Its hard to imagine a time without supermarkets, but it was on 4 August 1930 that the first true supermarket opened: King Kullen, in the United States, operating under the slogan Pile it high. Sell it cheap. Prior to this, shoppers made separate trips to the greengrocer, butcher, fishmonger, dry goods store, general store and bakery, where shop assistants would fetch, measure out and pack everything the customer required.

These new supermarkets had food departments and self-service, and by opening multiple outlets (the beginning of supermarket chains) they were able to sell larger volumes of food, lowering the prices. The idea spread to other parts of the world: the first UK supermarket opened in 1951 and the first Australian supermarket opened in 1960.

Today, 84 per cent of US shoppers buy their food primarily at a supermarket or supercentre (a discount department store that also sells a full range of groceries). In the UK less than 2 per cent of shoppers buy groceries from independent stores. The two biggest Australian supermarkets, Coles and Woolworths, along with Aldi make up 73 per cent of the Australian grocery market.

Supermarkets offer us food that is cheap, uniform in size and appearance, blemish-free, clean and pre-packaged, some ready-to-eat, abundant no matter what the season and from all the corners of the globe.

But this isnt actually how food grows. There are systems in place that allow this endless array of perfect produce, and these systems have limitations that are putting increasing strain on our planet.

The choice we are offered in supermarkets is eye-opening.

It seems that no matter where our supermarket is located, we can buy salmon from Alaska, apple juice from the UK, asparagus from Peru, white wine from California, olive oil from Italy, butter from New Zealand and biscuits from Australia.

The average supermarket today stocks 40,00050,000 different product lines. The problem with this choice is that all of these products have to be shipped, flown and/or freighted over hundreds (or thousands) of kilometres from farms and factories to the stores. Take imported asparagus, for example. In 2014 Australians spent almost $20 million on asparagus imported from countries including Peru and Mexico covering distances of more than 15,000 kilometres (9400 miles). The USA imported 228,000 tonnes (502.4 million pounds) of asparagus from Mexico, Peru and Chile in 2017. And thats just the asparagus.

The distances over which food items are transported during their journey from producer to shopper are known as food miles.

This means trucks on the roads, planes in the sky and container ships on the ocean, burning fuel and releasing emissions into the atmosphere. Transportation of food accounts for around 11 per cent of the greenhouse gases that an average household in the USA or the UK generates annually as a result of food consumption.

Trade is nothing new. Camels were domesticated in 3000 BCE, which allowed the opening of trade routes to import spices and other products. Later, boats expanded trade further. But trade today has been completely transformed: not just the types of products or the way they are shipped, but also the scale.

Products with a longer shelf life (or those that can be transported frozen) will often be shipped by boat or transported by truck rather than flown by plane, which reduces overall transport emissions. But this is not the case with many imported fresh fruits and vegetables. Fresh produce has a very short shelf life and needs to be air-freighted to reach stores soon after picking. Some very quick-to-perish foods such as berries may even be flown to stores within their country of origin.

Food miles arent the biggest greenhouse gas contributor when it comes to food production and consumption, but they are still significant when we consider that much of this transportation is so that we, as shoppers, have a choice of products.

This choice often doesnt even mean exotic ingredients. In many cases supermarkets are sourcing products from far-flung places when they could find something local that is equally as good. Its not that its necessarily cheaper or better to do so sometimes theres the prestige associated with stocking certain products, or its the power that big corporations have to push their own brands into stores.

Next page