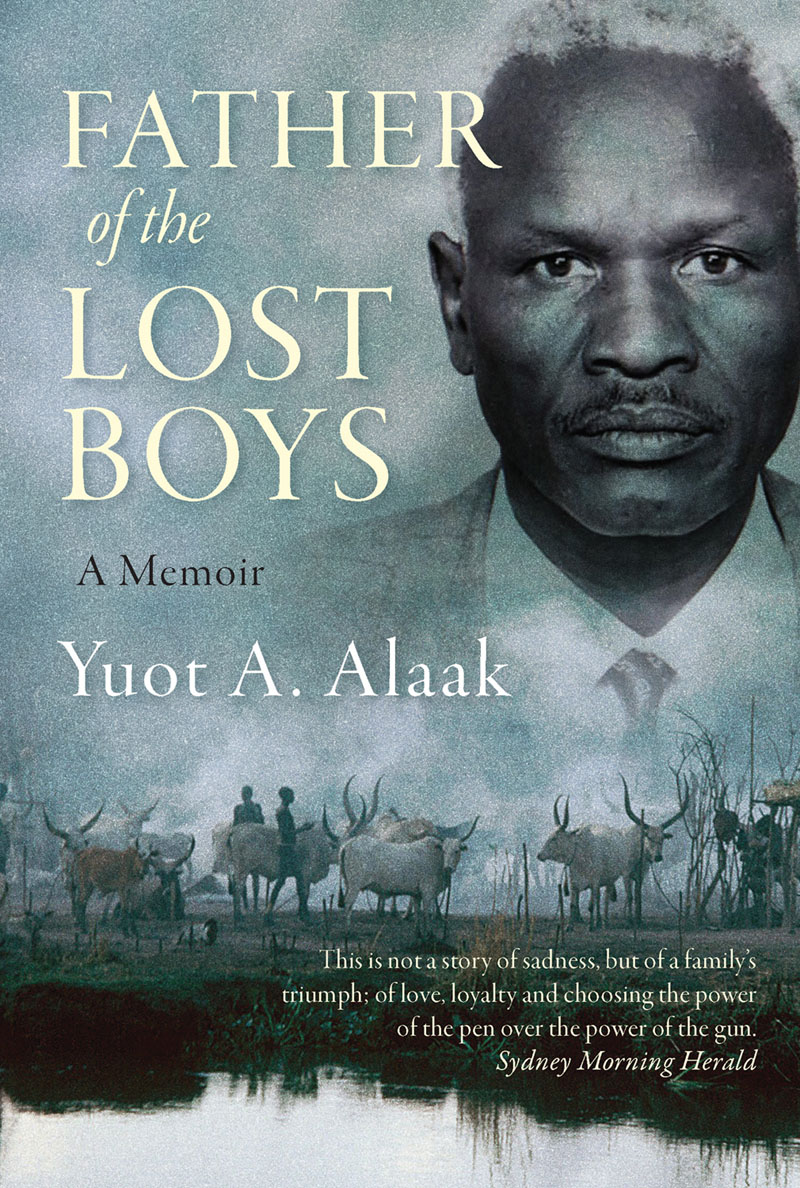

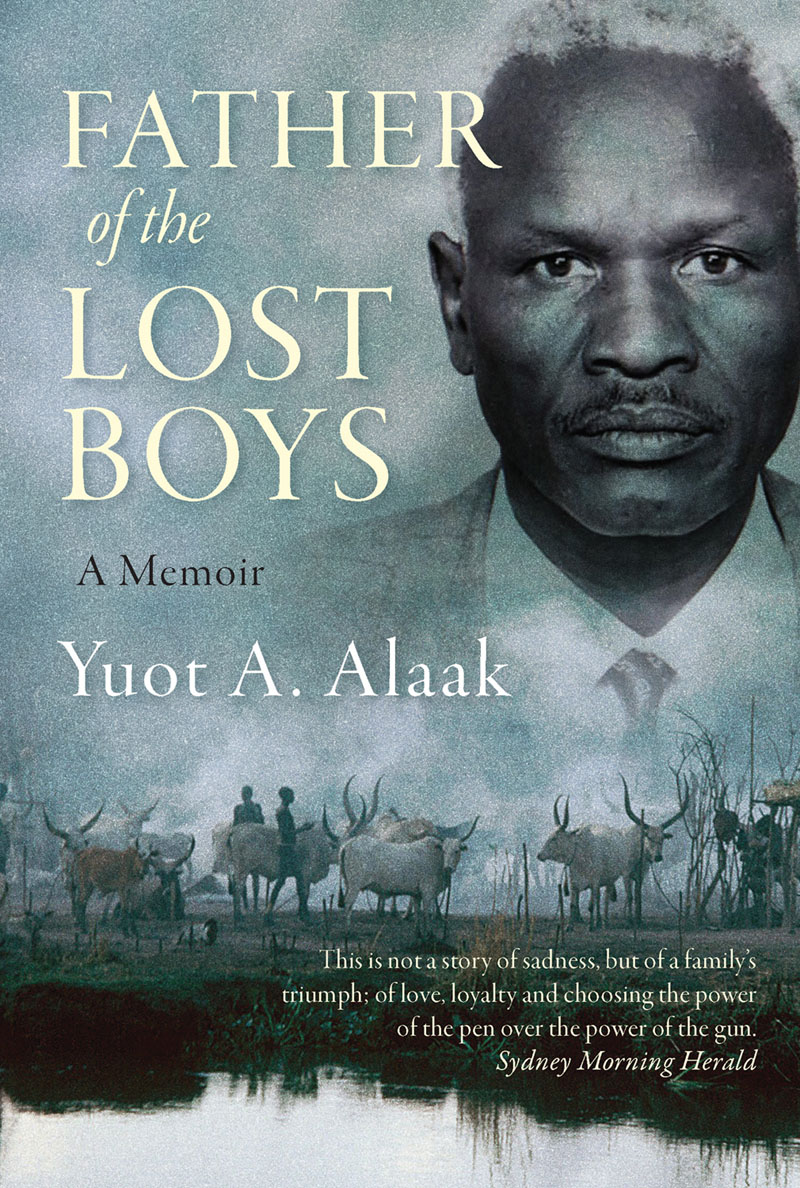

Yuot Ajang Alaak hails from the village of Majak in South Sudans Jonglei State. He migrated to Australia as a refugee with his parents in May 1995, having spent most of his childhood in Ethiopian and Kenyan refugee camps. Yuots short story The Lost Girl of Pajomba was anthologised in Ways of Being Here (Margaret River Press, 2017). Father of the Lost Boys is his first full-length work and was shortlisted for the 2018 City of Fremantle Hungerford Award. In his day job, Yuot is a mining professional with degrees in geoscience and engineering, and has worked for some of the worlds largest mining companies. Yuot calls himself a proud South Sudanese Australian and lives in Perth with his family.

Instagram/Twitter: @yuotalaak

Email:

FOR MY PARENTS

for being my foundation and my inspiration, for always daring to dream, and for never giving up, even when all seemed lost.

AND FOR THE LOST BOYS

whose spirit of perseverance still inspires me today;

youre the greatest generation in our countrys history.

Your sacrifices will always be remembered.

My South Sudan

My Love

My everything

To you I belong

For you I long

As the sun rises

My dreams of you awake

Once more

Contents

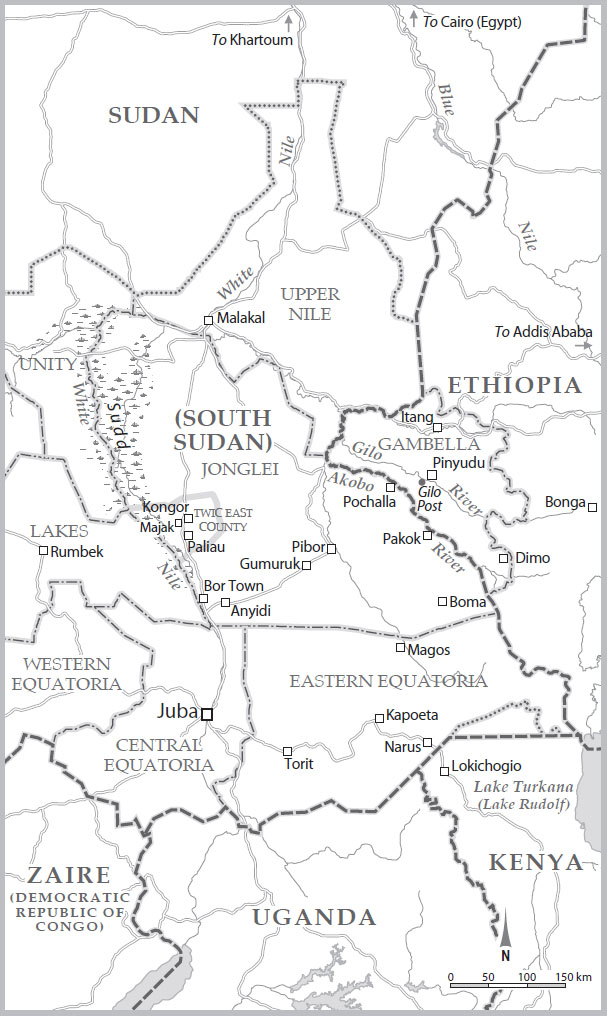

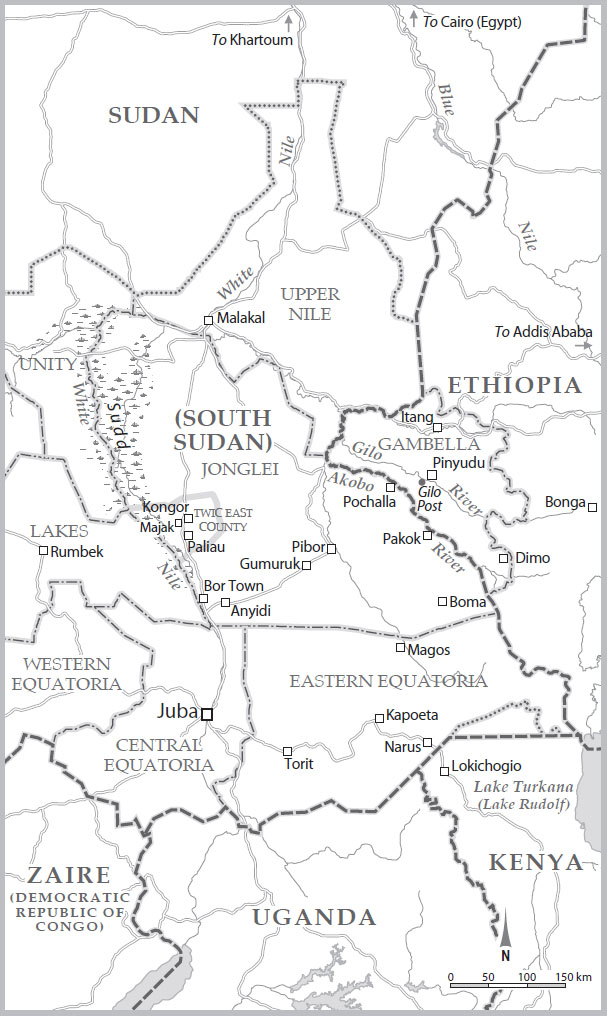

Map of Sudan and Ethiopia, early 1990s

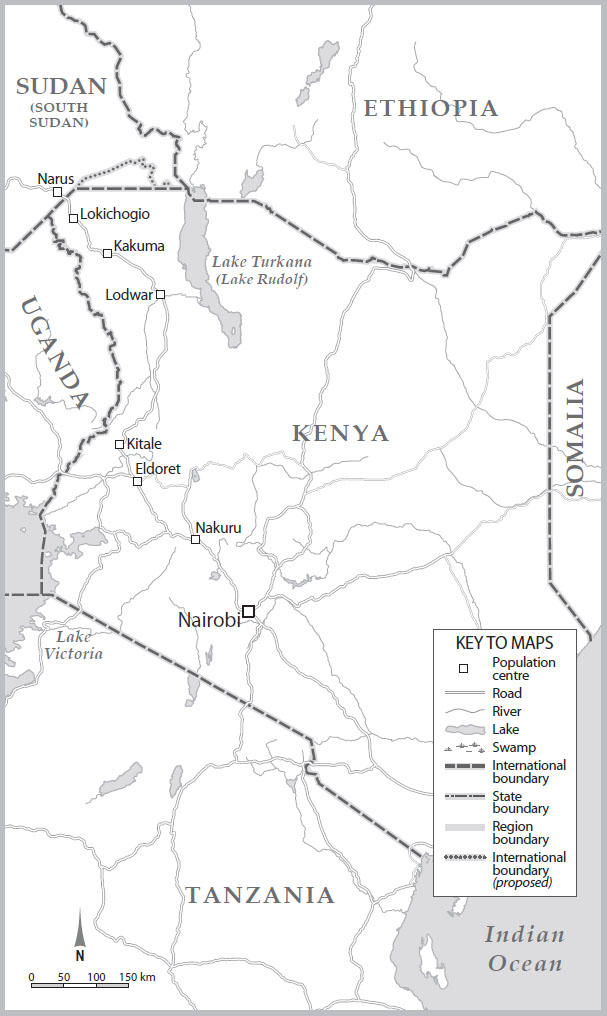

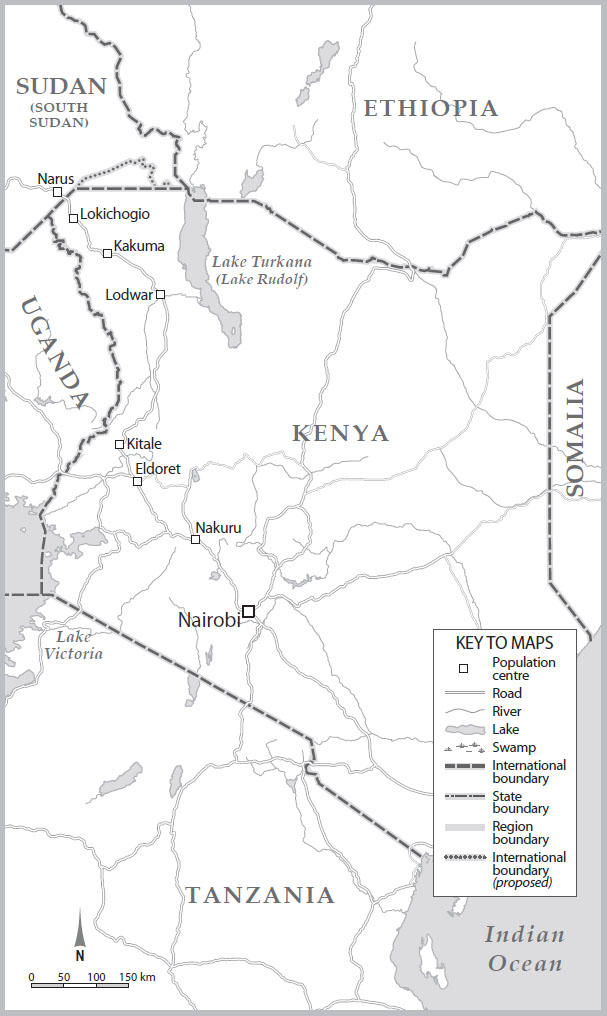

Map of Kenya, early 1990s

Authors note

The events of this book occurred primarily during the Second Sudanese Civil War (19832005), but are more broadly reflective of Sudans turbulent history. Myriad events over the past century have contributed to the conflict that still rages today. The creation of the country called Sudan, or the Sudan, which was arranged by the British in the second half of the twentieth century, led to a tragedy that produced thousands of heroes, and shattered the dreams of millions. It rendered tens of thousands of boys lost to their families. But it also produced a great man to lead them. A leader and a teacher, a father to these Lost Boys: my father, Mecak Ajang Alaak.

In a place that has endured so much conflict for so long, there are as many points of view as there are stories to be told. The story that follows is my story, and one I am lucky to have survived to tell. For readers who seek further historical background, my summarised account at the end of this book, Historical overview of conflict in the Sudan, provides a context for the story of the Lost Boys. It helps to show why there has always been marginalisation and conflict in the Sudan and why, even today, my beloved people are a displaced people.

Prologue

As the summer sun rises over Kongor, voices of joy come from the distance. The land is green and dotted with rain-filled ponds. It has poured overnight, as it has on the previous five nights. The voices get louder as more and more women emerge from their huts to join in the singing. Within hours, the family compound is full of women dancing and singing. The village resounds with voices synchronised in a smooth melody, pronouncing the arrival of a baby boy the son of a chief. Standing tall and proud, Alaak Arinytung looks on. He knows it will be weeks before he can hold his newborn. The tradition of his people bars him. His mother, Akuol, stands beside him, her right arm wrapped around his shoulder. Fears of evil spirits and infection mean very few people will get to see the child for weeks.

Akuol walks to the hut and catches the eye of Abul, her daughter-in-law and the proud mother of the baby. Their faces break into broad, gentle smiles.

Congratulations, she says to Abul. You have given us a handsome grandson. He will be a great wrestler and singer.

As news spreads to neighbouring villages, more people come to congratulate Alaak on the birth of his son. A white bull is slaughtered and the village is joyous with celebration.

Weeks pass and Alaak becomes increasingly anxious to hold his son, but he maintains an outward calm. He knows his mother Akuol and his wife Abul are taking good care of the newborn boy.

Finally, the wait is over. Young men arrive in droves from the cattle camps. Girls wear colourful beads, faces covered in The excitement becomes electric. Bulls and goats are slaughtered to mark the occasion, as the voices of men and women, the young and the old, mingle in a rhythmic melody that threads its way into the surrounding bushes and beyond.

When Alaak arrives, he stands tall and proud, his spears glittering in the midday sunshine. His father, Yuot, stands beside him. As the circle of wellwishers tightens around the hut, Abul senses the moment is near. At any moment, Akuol will ask for the baby to be taken outside and presented to the tribe for the first time. Now Yuot bends down and crawls into the hut. He looks proudly at his grandson. He blesses the baby by spitting on his head a common practice. Abul gently hands the baby to Yuot. Holding his grandson for the first time, his face breaks into a wide, bright smile. His white teeth glow in the light that filters into the grass-thatched hut.

Drums outside beat louder. The singing reaches fever pitch. The ground shakes as feet stomp. Excitement fills the air. Holding the baby carefully, Yuot crawls out of the hut and gets to his feet, then holds his grandson aloft.

The gathered clan members break into applause, their voices rising in jubilant song. As the singing begins to subside, Yuot speaks, still grinning. He congratulates Alaak and Abul for giving him a healthy, handsome grandson.

Raising his voice, he proclaims, I give each of you a new member of our tribe. I have named him Ajang. He is of the people and shall be for the people. He will become a good wrestler. He will be a proud Muonyj.

The crowd applaud again and their dancing, singing, clapping and stomping resumes. Songs incorporate the babys name Ajang! Ajang! Ajang! into their choruses. Alaak and Abul look on proudly as Ajang is passed from one tribal elder to another, each blessing him in his own words. Celebrations run late into the night, and continue for days. The boys full clan name is to be Ajang Alaak Yuot Alaak. This is to separate him from the rest and set his path. A new era has begun for the family, the clan and the tribe.

Ajang grows up to become a strong, healthy boy. He displays leadership and is admired and respected by his peers. He thrives in his tribes culture and way of life. In his home village of Majak, Ajang and his friends sit under trees and play all day. Using the sticky clay soil that lies beneath the village, they make replicas of the best huts and biggest bulls they see in the village and cattle camps. They stage mock bullfights with their beautifully crafted creations. They zigzag around the huts as they try to catch each other. Often, they take goats out for morning and afternoon grazing. While their goats graze, the boys fish in the ponds and waterways that surround the village, and practise their wrestling skills. Wrestling is the favourite activity of the Dinka. Boys start to practise as soon as they can walk. By the age of ten, Ajang excels at wrestling. No boy his age is able to defeat him. Ajang also helps his mother attend to the family farm and cattle.

Next page