The right of Martin Doerry to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

Visit www.bloomsbury.com to find out more about our authors and their books. You will find extracts, authors interviews, author events and you can sign up for newsletters to be the first to hear about our latest releases and special offers.

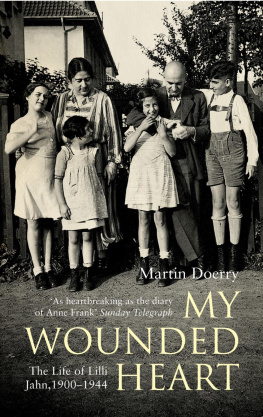

Lilli Jahn's fate was never deliberately concealed from her grandchildren, yet her story remained both vague and incomprehensible - indeed, mysterious - and was only ever hinted at in two or three simple sentences. Grandmother Lilli, it was said, had been murdered in Auschwitz. Her husband Ernst Jahn had divorced her, thereby leaving her, a defenceless Jewess, at the mercy of the Nazis.

Lilli's children told their own children no more than that. They would undoubtedly have said more if asked, but they were not alone in being burdened with the traumatic enormity of what had happened; it also weighed on Lilli's grandchildren in the form of an unspoken ban on asking questions.

This taboo prevailed for decades in many families - those that included victims and perpetrators alike - and it was not until the 1990s that it lost some of its force and significance. A new generation began to question the causes and consequences of National Socialism more thoroughly than ever before, and it was this debate that suddenly dissolved the mental block with which many survivors of the Holocaust and their families had sought to shield themselves from their own emotions. That which had for half a century been little more than a past that numbed their minds, overshadowing all else, was now recalled with vivid and often distressing clarity.

When Lilli's son Gerhard died at Marburg in October 1998, his four sisters also embarked on this process. Gerhard Jahn, a Social Democrat politician and minister of justice in Willy Brandt's cabinet, had left them an unexpected and startling bequest: several cardboard boxes and large envelopes containing some 250 letters written by Lilli's children to their mother in 1943 and 1944, when she was already detained in a labour camp.

Although the sisters naturally remembered these letters, they had no idea that their brother had preserved them for more than five decades. No one had ever mentioned them.

One day early in 1999 Lilli's daughters sat down together and looked through their brother's bequest. They took it in turns to read their own letters aloud, sometimes weeping, sometimes laughing at their childish naively. Then they replaced them all in the boxes and envelopes and consigned them to oblivion once more.

But memories thus revived could not be suppressed. Ilse, born in 1929 and the eldest of Lilli's daughters, gradually told her three children about what had been found; Johanna, the next in line, also called her four children together and recounted Lilli's story to them. Eva, the third daughter, was initially reluctant to come to terms with her letters and did not read them thoroughly for some time. As for Dorothea, she had been only three years old in 1943 and not yet able to write.

It was a minor miracle that the children's letters had survived at all. Lilli had managed to smuggle them out of Breitenau corrective labour camp, near Kassel, in March 1944, just before she was transferred to Auschwitz. A wardress had probably done her this last favour. And, since Lilli herself had by then written a whole series of letters to her children, most of them mailed illicitly, there now emerged a complete picture of the dramatic events of autumn and winter 1943-4.

Ilse's son, the author of these lines, at first undertook simply to organize and copy the correspondence for the family's benefit. Before long, however, questions arose of which one, in particular, required an answer: Why had Ernst Jahn divorced Lilli in 1942, knowing that this would sentence his Jewish wife to certain death? Or might he not have known it at the time?

Suddenly, the background to their marriage acquired greater importance. How had Lilli come to marry Ernst, a Protestant? How had he behaved during the first few years after the Nazis seized power?

Further research unearthed still more letters. It soon transpired that each of the sisters possessed documents relating to their mother, or letters from her, of which the others knew little or nothing. Eventually, more than 300 letters written by Lilli between 1918 and 1944 came to light. Together they convey a graphic picture of the stigmatization, isolation and persecution to which she and her children were increasingly subjected.

The question that now arose was whether the correspondence should be published. Gerhard Jahn had been very critical of any attempt to make Lilli's Breitenau letters accessible to a wider public during his lifetime, and had largely succeeded in preventing this. But what were his motives? Was he afraid that it would open old wounds of his own? Lilli's daughters, too, could not at first conceive of exposing their mother's sufferings to strangers. They feared that their privacy would be invaded and their personal emotions and memories despoiled by a Zeitgeist fixated on the Holocaust.

So why should Lilli's story be told at all?

One simple answer is that each new biography or autobiography and each authentic source relating to the Nazi era reaches new readers. If only on that account, they benefit the political culture of the present day and the historical awareness of future generations.

A rather less straightforward answer is that most if not all autobiographies recount the experiences of a survivor. Whether it be Primo Levi, Victor Klemperer, or Ruth Klger, each of these authors tells of atrocities and tribulations from the standpoint of someone who escaped them. Those who read their books with care can certainly perceive the misfortune of six million murder victims through the good fortune of the handful who survived. What is missing, however, are the experiences and perceptions of those who did not survive the Holocaust. Exceptions do exist, of course, foremost among them the diary of Anne Frank, but the typical literary form follows the Schindler pattern: an adventurous escape from direst peril. For anyone unable or unwilling to grasp the dialectical significance of such accounts, these memoirs combine to form the strangely distorted picture of a reign of terror from which the majority did, in the end, escape.

Lilli did not escape it. At bottom her fate is merely representative of the fate of millions, but every victim of the Holocaust has a very special story of his or her own to tell. As Sebastian Haffner says in Defying Hitler, anyone wishing to know something about the crucial historical watershed of 1933 must 'read biographies, not those of statesmen but the all too rare ones of unknown individuals'. Lilli Jahn's biography is that of a private individual: a Jewish physician who was an alert contemporary observer of Germany in the 1920s and 1930s; an emancipated woman who loved her profession but was, at the same time, wrapped up in her role as a mother; a literary and musically gifted intellectual who conducted theological and philosophical discussions with her friends. Above all, though, Lilli was an ebullient, high-spirited woman so deeply devoted to her husband that she quickly succumbed to her own illusions about him and suffered severely in consequence.