T here are a million ways to slice an apple. It is delicious, nutritious, artistic, sensual, culturally loaded, historically significant, a horticultural marvel, challenging to grow, and a commodity in the marketplace. It is ancient, but it is constantly reinventing itself.

There is no more democratic fruit. No food is as generous and versatile. Virtually everyone has tasted an apple; most people eat hundreds of them, fresh and cooked, use cider vinegar and other products made from apples, and imbibe gallons of its juice. Apples frequent our lives, from the McIntosh at lunch to an apple pie at Thanksgiving.

Apple trees are a distinctive feature of the New England landscape. They appear in a variety of settings: older, standard-size trees with gracious limbs and thick canopies; dwarf trees packed tightly together along long, parallel rows, harnessed to trellises; a lone, twisted tree growing wild along a stonewall; or small clusters in half-acre fields and suburban lawns.

For centuries and across cultures, from Adam and Eve to ancient Greece, apples have filled peoples minds as well as their stomachs. The history of New England apples is much shorter, of course, and to date it has not produced any new myths (except for the larger-than-life figure of Massachusetts native John Chapman, better known as Johnny Appleseed). In New England, new apple varieties proliferated in the 17th, 18th, and early 19th centuries and were typically named for the town, person, or orchard where they were discovered. Many of these apples have illustrious or odd histories that have been preserved for generations. Biting into a once-popular apple discovered in New England tangibly connects us to our past. So does the enduring presence of an abandoned orchard that still produces gnarly fruit. Apples and the stories about them offer insight into more than simply diet, but also aesthetics, horticulture, weather, industrialization, and the marketplace.

Each piece of grafted fruit is a direct descendent of the original apple tree, some centuries old, for which it is named. It is hard to imagine orchards today in such urban settings as Dedham (Benoni, early 1800s), Roxbury (Roxbury Russet, 1635), or Wilmington, Massachusetts (Baldwin, 1740), but the persistence of these varieties reminds us of those communities agrarian roots.

Commerce and culture, rather than the orchard, are the sources of contemporary apple myths, having appropriated images of apples to symbolize innovation and style, from the Beatles green Apple Records label in 1968 to the stylized logo of the Apple computer company in 1976 to countless interpretations of the Big Apple since it became New York Citys nickname in the 1920s. Whether we eat them or not, apples are firmly in our consciousness.

Yet eating them, after all, is the main reason why we hold apples in such high esteem. No other food can be used in as many ways as apples, in so many circumstances. Apples combine sweetness with a refreshing, complex tartness, with hints of a wide range of unusual flavors: pear, citrus, pineapple, strawberries, nuts, spices, and vanilla, among others. An apples flesh can be hard or soft, light or crunchy. Nearly all apples contain juice; some explode with it.

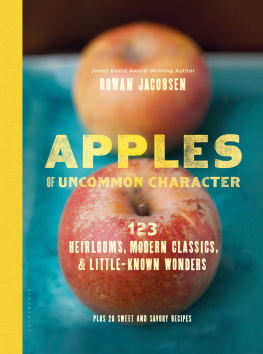

Apple flavor generally is at its most intense when the fruit is eaten fresh off the tree, although the flavor of certain varieties noticeably improves in storage. For weeks or months after they are picked, apples retain their flavor and crispness in a variety of ways: fresh or cooked, with other foods, sweet or savory, served during any course of any meal on any occasion. It is no accident that colorful displays of apples are often among the first foods to greet shoppers in the grocery store. Entire cookbooks have been devoted to not just the apple, but to apple pie.

When pressed into juice, apples can be transformed into hundreds of drinks, from fresh and hard cider to brandy and ice wine, alone or blended, tasting very unlike the whole fresh apple. Similarly, apples are processed into many foods, distilled into kitchen staples, such as vinegar; dried for baking; and made into sweet foods, such as apple jelly or boiled cider.

In addition to their versatility and flavor, apples are healthy: sweet but fat free and low in calories, loaded with pectin, a good source of fiber, and full of flavonoids, phytonutrients, and antioxidants, all of which may help reduce the risk of developing cancer, hypertension, diabetes, and Americas leading killer, heart disease. Apples are convenient, fitting in the hand and carried anywhere. With so many varieties and so many ways to eat and serve them, apples are a universal food, experienced by all.

The apple derives much of its cultural meaning from its rich history and because it is good to eat. But its physical beauty adds greatly to its symbolic power; Eve bites into the apple only after she has been seduced by its outer beauty, after all. Our desire for this fruit is so great, it triggers not just admiration but also lust and greed. The apple is so irresistible it becomes the perfect bait for the Witch to poison Snow White. A golden apple symbolizes the passion that led to the Trojan War.

How can a piece of fruit inspire such profound cautionary tales? Perhaps it is because we experience the apple through multiple senses: we taste its flesh, inhale its aroma, and admire its compact shape and multicolored skin. The apple is a fragrant work of art, alone or in bins, grouped with other apples, or hanging on the tree. It grows in brilliant shades of red, green, orange, and yellow, in solid colors, stripes, streaks, or patches. Some apples have intricate, meshlike patterns of russet on their skin or are completely covered in it, leaving them with a golden brown, sandpaper-like surface. An apples skin has small pores called lenticels for respiration; on some varieties they are barely visible, but on others, white or yellow lenticels are as prominent as seeds on a strawberry. Apples are both paintings and sculpture, coming in various shapes, from slender and conical to flat and round, as big as a grapefruit or as small as a radish.

For all of its compact beauty, though, an individual apple is a mere detail, a speck in the larger canvas of the orchard. The aggregation of apple trees in an orchard creates a rare, dynamic landscape through the four seasons, beginning with spring bloom in May, when the trees flower en masse, every one covered with pink blossoms. It is a spectacular sight.

Even a few apple trees planted together command our attention. To walk through an orchard in midsummer, it is hard not to feel uplifted by the presence of thousands of pieces of healthy, maturing fruit hanging from every limb. In late fall, the leaves on many apple trees turn as brilliant as any oak or maple, and the bold, graceful gestures of leafless trees, especially the old standards, impart a rare beauty to the orchard in winter.

But it is during the fresh harvest months of September and October that the orchard hits its sensory peak. The trees and the grass beneath them are lush and green, pleasantly muffling sounds. Birds, distant tractors, or other sounds can be heard, but for the most part the orchard is a quiet place. The ripe apples on the trees are dazzling to the eye, their profusion overwhelming at times. The orchard air is perfumed, lightly scented with sweet apples, and the experience culminates in the rich, tactile pleasure of grasping an apple with ones fingers and biting into its crisp, juicy flesh.

The apples unparalleled status as superfood, historic icon, and art object all contribute to its cultural meaning. But especially in such places as New England, apples are also part of the fabric of the communities where they are grown. New Englands apple industry, though small nationally, is incredibly diverse. People grow apples on all scales, from a few backyard trees to a hillside of heirlooms to a 10-acre pick-your own with a retail stand, to a 350-acre orchard growing apples strictly for the wholesale market. Some of our neighbors have grown apples for generations; refreshingly, despite the difficulties (including the high cost of land), some are starting out for the first time. Apples are a cash crop or a curiosity, a commodity and livelihood, depending on ones commitment and approach. For many, growing apples is a lifestyle, a demanding, 12-month job intimately connected to the natural world and its rhythms in the ancient, sacred task of growing healthy, nutritious food. In New England, many of the people who choose this lifes work share the experience, inviting the general public to enjoy their privately maintained land with pick-your-owns, tours, farm stands, petting zoos and other activities, in what amounts to a public-private partnership.