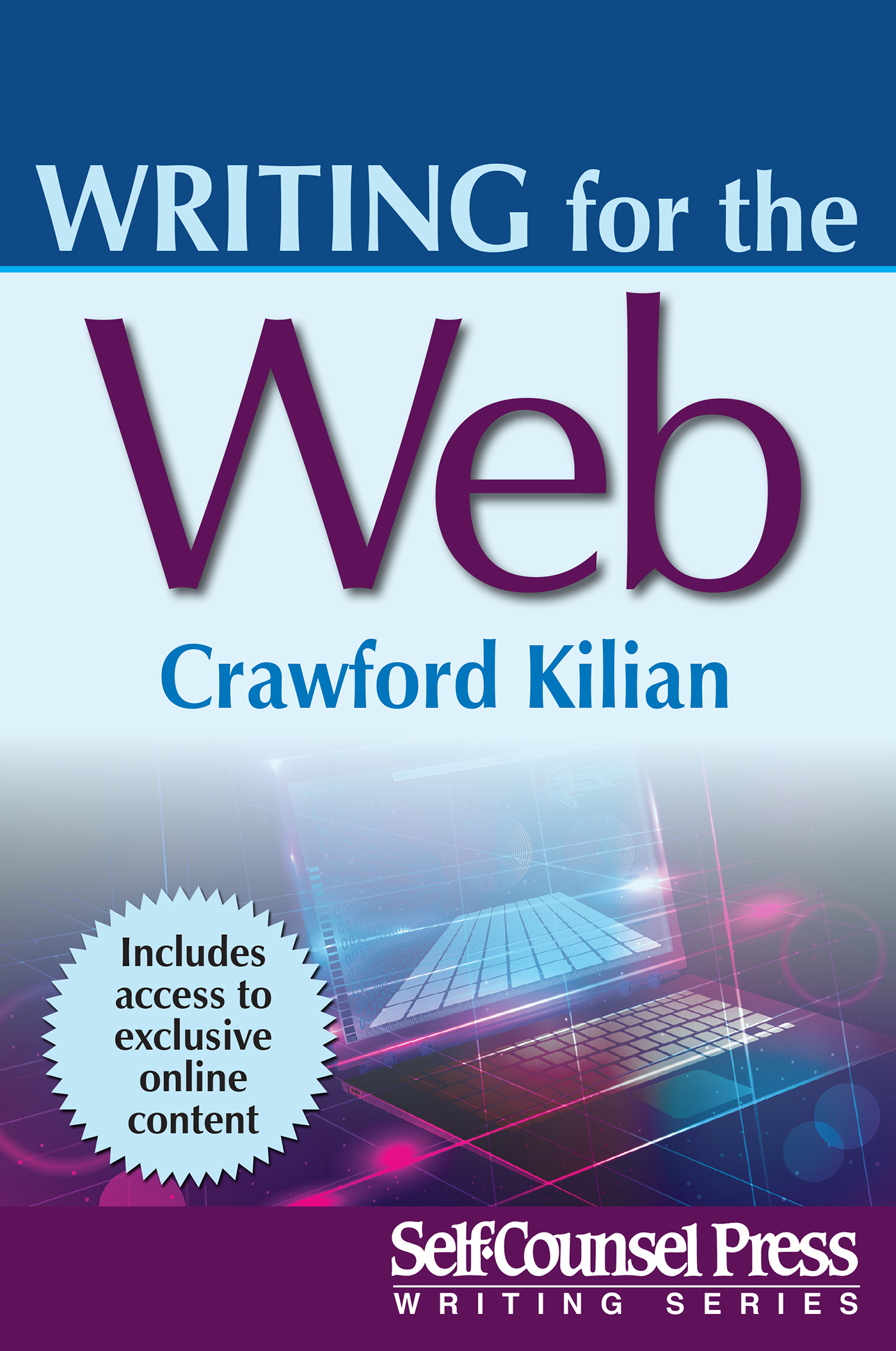

Crawford Kilian - Writing for the Web

Here you can read online Crawford Kilian - Writing for the Web full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2015, publisher: Self-Counsel Press, genre: Home and family. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Writing for the Web

- Author:

- Publisher:Self-Counsel Press

- Genre:

- Year:2015

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Writing for the Web: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Writing for the Web" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Writing for the Web — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Writing for the Web" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

For over 40 years I taught workplace writing, freelance article writing, and how to write commercial fiction. This is my 20th book. So Im pretty dedicated to print on paper as a medium of communication.

But in the late 1980s I began to see how networked computers were changing the way we communicate. In some ways they were just another means of getting print on paper. But something about the medium itself was changing the nature of our messages and changing our relationships with the people with whom we communicated. First in email, and then on the newfangled World Wide Web, we were reading, writing, and reacting to information in different ways.

In teaching technology students in the early 1990s, I had to learn fast to stay ahead of them. We were all scrambling to master the new grammar of multimedia: the ways that text and sound and image could combine to express ideas. With few authorities to consult, my students and I watched what we ourselves were doing, and we tried to draw general principles from our experience.

By the mid-1990s the web was truly worldwide, and a whole new industry arose to serve and advance it. I got a sense of how big it was when I walked into a university bookstore and found, by rough estimate, 170 shelf-feet of books about the web: how to master HTML, CGI, and Java; how to use this or that browser; how to design websites; how to research the exponentially growing resources available on the web.

Not one of those books dealt with the actual words to be used on the web.

Well, that made a certain amount of sense. No one had enough experience yet to say what would work on the web, and what wouldnt. Hypertext had been around in various forms since the 1970s, but it wouldnt necessarily work on the web the way it does, for example, on an encyclopedia DVD.

So most of the web pioneers wrote in whatever style seemed comfortable, and other pioneers followed their lead. Thats why, in the late 1990s, so many sites had expressions like Check it out and This site under construction.

By then, creating websites had changed from a self-taught skill into an industry. The pioneers had given countless hours to trial and error (mostly error), in learning the basics of a new technology. But they couldnt squander their time when clients were paying for it. An obscure computer specialty in 1992 had, by the end of the decade, become almost a basic job skill. My own colleagues, teaching in fields like tourism and business administration, began to wonder how they could cram website design into an already crowded curriculum.

So the time seemed right for a book that might help both expert and novice webwriters save time and avoid known pitfalls. It might thereby help web users as well.

This book doubtless reflects my own biases toward print on paper, but I have tried to learn from a wide range of self-taught pioneer web authorities and to present their views as well as my own. If my arguments make sense and help you write successful text for your sites, of course Ill be delighted. But I look forward to being rebutted and superseded, because better insights will make webwriting a more effective communication tool for all of us. Some of my arguments may provoke you into articulating contrary views that help to make your sites succeed. If so, this book has succeeded too.

In mastering webwriting, we learn about what goes on in other kinds of writing too, and what goes on in our own minds. So in learning to write well for this medium, I think we learn how to write better in all media, and we learn something about ourselves as well.

Twenty-five years after Tim Berners-Lee wrote his first proposal for a large hypertext database with typed links, most of us dont know how we ever got along without the World Wide Web. Yet old habits die hard, and we still use the web with habits acquired in other media.

So newspaper websites still look a lot like newspapers. TV station websites offer lots of video. Business websites look like their ads in the Yellow Pages, only with more colors. And most website creators treat it like whatever medium theyre most familiar with: a sheet of typing paper, a radio, a canvas, a family photo album, or a Rolodex.

Websites can serve all those functions, but one of their primary purposes is to make large amounts of text available online. (The Latin word for web, by the way, is textus.) Graphics and sound can enhance the content of a site, but text remains the core.

The web is a very different medium from print, TV, and radio. But the habits weve learned in those media influence the way we respond to text on the computer screen. We even call web files pages when theyre nothing of the sort.

We read print documents in a certain way, using cues to navigate through a familiar format. The indented first line of a paragraph tells us a new topic is coming up. Page numbers establish a sequence were happy to follow. Indexes use alphabetical order to help us find things. Were so used to these conventions that we dont even notice them.

But print habits dont apply on the web. We surf through TV channels with our remote controls, and we bring the same attitude to the TV-like screens of our computers: deliver something interesting right now, some kind of jolt or reward, or well go somewhere else.

These responses demand a kind of writing that is different from other media not better or worse, just different. Effective website creation can certainly include excellent video, graphics, and sound. But it also means text that can interest impatient surfers and make them read what youve written.

This book offers some principles for composing text for your website. The principles arent carved in stone (how could they be?), but they arise from the experience of thousands of people writing online and on the Web over the past 25 years. We can draw some general conclusions from that experience: what works and what doesnt. We can also modify or ignore those conclusions if our own circumstances require us to. When George Orwell compiled his list of rules for clear writing, he saved the best for last: Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous. Good webtext has a lot in common with good print text. Its plain, concise, concrete, and transparent: Even on a personal website, the text should draw attention to its subject, not to itself. This book will give you plenty of exercises and tips for developing such a writing style.

Like good print text, webtext carries a subtext, a nonverbal message. The message may be, Im comfortable in this medium and I understand you, my reader. Or it may be, Im completely wrapped up in my own ego and my love of cool stuff. This book should help to sensitize you to any writing habits that may let the wrong subtext slip out.

I cant tell you how to design your site. But I can try to alert you to the likely results of your design decisions. For example, if you like long, long paragraphs full of long, long words, most of your readers will soon lose interest in what you have to say.

Similarly, if your text scrolls on forever, you will lose readers. If you build your site with layer after layer of linked pages, you will likely baffle and bore your readers.

If you are creating your own commercial site, or a personal blog, you decided the content and the structure: its topics, its size, how its pages connect, how its graphics, text, audio and video work together. For reasons Ill discuss, you can easily undercut yourself by presenting text as if it were still on paper. So its in your own interest to understand something about website design basics, especially as they affect the display of your text.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Writing for the Web»

Look at similar books to Writing for the Web. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Writing for the Web and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.