Table of Contents

FOR LAURA

PREFACE

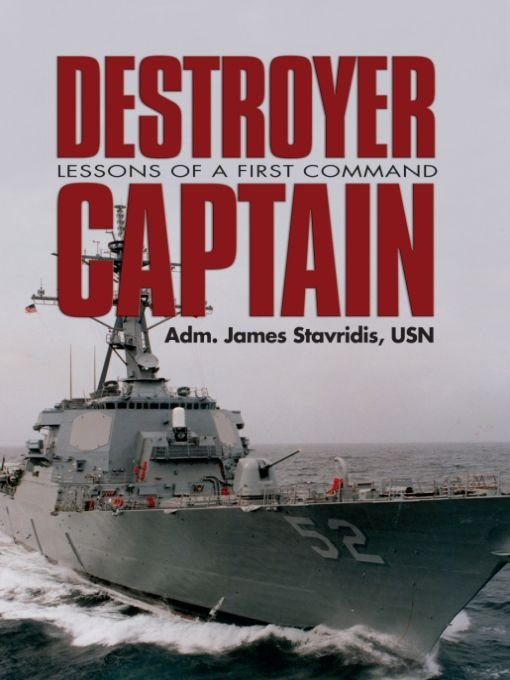

When I was assigned to my first command at sea in 1993, I decided to keep a journal. I never thought it would be something I would publish. Rather, I intended it to be a sort of personal memoir of what I hoped would be an interesting and productive time in my life.

I was in my mid-thirties when I was initially detailed to the USS Barry, a brand-new Arleigh Burkeclass Aegis guided-missile destroyer. I was married to Laura, a wonderful and Navy-experienced wife, and we had two small daughtersboth under the age of ten. I knew that the hardest part of the job by far would be the immense amount of time I would spend away from the three of them, sailing from the ships home port of Norfolk, Virginia. Yet, it was very clear to me that this command was something I wanted to do and had been preparing to undertake for over twenty years, since I walked through the gates at Annapolis and entered the U.S. Naval Academy in the hot, humid summer of 1972.

The Barry was recently commissioned, and I would be only the second commanding officer, an enviable position indeed. Serving as the second skipper of a warship is usually thought to be the best spot for the simple reason that the first CO is charged with building the ship through the long construction process, while the second captain generally has the far more enjoyable task of taking the ship forward on her first deployment. Such was the case for me in the Barry, and I was truly excited.

Arleigh Burkeclass destroyers are built from the keel up to fight. They are largely constructed of solid steel after some unhappy experimentation by the Navy with more aluminum in the hull and masts in early ships during the late twentieth century. The ships are outfitted with the formidable Aegis combat system. Aegis, which means shield in Greek, is a complex suite of sensors, weapons, and command/control elements that collectively permit the ship to track targets in the air, on the sea, and under the water for many miles around the vessel. Notably, the air search radar systems can find incoming missiles and aircraft at distances up to 250 miles (and beyond, when used against ballistic missiles). The ship also carries a large number of long-range missiles, including the deadly Standard air defense missile and the long-range land-attack Tomahawk missile.

The crew numbers about 340. The Barry shifted from having only men in the crew to a mixed group, with approximately 15 percent women, about halfway through my tour. She was the first destroyer in the Navy to embark women as part of the crew, and their successful integration was a significant achievement for the ship. Without question, the very best and most enjoyable part of commanding a U.S. Navy warship in the all-volunteer force is interacting with the young men and women who crew her. They are in every sense of the word inspirational, and a major part of this memoir is their story as well. The namesake for the class, Adm. Arleigh Burke, a fighting admiral of the Second World War, often said that our young Sailors, commissioned officers and enlisted, are the best of us all, and the hope of our future as well. I could not agree more after a lifetime of service with so many of them at sea.

The mid-1990s were a trying time for the U.S. Navy. We were dramatically reducing the number of ships in the fleet as part of the postCold War drawdown, and as a result, the remaining shipsespecially the surface ships like minewere sailing with great frequency. As you will discover in the course of this story, I would eventually sail well over 150,000 nautical miles at sea. The Barry would play a role in world events, including the UN operations off Haiti in the fall of 1993, the embargo operations off the Balkans in the summer of 1994, and the response to Saddam Husseins ill-fated thrust toward Kuwait in the fall of that same year.

The ship would also sail on countless training and exercise evolutions, make many port visits in the interest of diplomacy, and show the U.S. flag throughout the Caribbean Sea, Atlantic Ocean, Mediterranean and Red seas, and the Arabian Gulf. We were out of our home portand away from our familiesnearly 75 percent of the time during the twenty-seven months I was in command. The stress of the so-called Operations Tempo or OPTEMPO, of those days eventually led to congressional hearings in which I was selected to represent the Navy, a story told in later pages.

But all of that was in the future in the spring and summer of 1993, which is when this memoir begins. As this Journal of a First Command opens, a young commander is undergoing firefighting training in Newport, Rhode Island, with his classmates and friends, who are also en route to command at sea. It seems a long time ago.

Today, in the spring of 2007, as I write this preface some fourteen years later, I am wearing the four stars of a full admiral, and I lead a joint command with thousands of Soldiers, Sailors, Airmen, and Marines spread across the thirty-two countries and fifteen territories of the Caribbean and Central and South America. Headquartered in Miami, Florida, I command the U.S. Southern Command, reporting directly to the secretary of defense and the president. It is a long way from a commanders silver oak leaves and life on the USS Barry.

Indeed, my life in my fifties has moved on in ways I truly would have thought unimaginable in my thirties and seems so much more complicated, as is the case for most of us. Yet, I find that the occasionally uncertain and certainly unguarded voice of the young commander in this brief memoir still evokes for me both the best of times and the greatest of challenges in my life and lies at the heart of what I have learned and understand today about leadership and what is so aptly known as the call of the sea. I publish it in the hope that it will shed some small amount of light for the public on what it means to be lucky enough to command a U.S. warship at sea and to share, if only for a moment, the occasional doubts and small victories of a young officer sailing the worlds seas in the turbulent closing days of the twentieth century.

The fire exploded in my face. I dragged the heavy nozzle of the fire hose toward the flames and pointed the solid stream of water toward the base of the fire.

For a long moment, the water had no effect. Then, as the sweat poured down my face inside the stifling oxygen-breathing apparatus, the flames flickered, seemed to sputter as the water continued to pour over them, and suddenly died, changing to a heavy blanket of steam, choking and hot, filling the tiny space.

I backed the hose team out of the small, brick-lined enclosure and turned to face my fellow firefighting trainees, five of whom had been backing me up during my turn as the nozzleman, leading the charge at the fire. We breathed a collective sigh of relief and pulled off our masks.

The faces that emerged from the masks were of men in their late thirties and early fortiesfaces just beginning to show the deepening concerns and cares of age, the sense of maturity that settles into the faces of people moving slowly but reasonably successfully along the carefully orchestrated career pattern of a military officer.

And each face showed the characteristic lines around the eyes common to Sailors who spend long hours staring at the distant horizon of the sea.