For the family, especially Philip who was not there.

Published by University of Otago Press

PO Box 56/Level 1, 398 Cumberland Street

Dunedin, New Zealand

Fax: 64 3 479 8385. Email:

First published 2004

Copyright Michael Shackleton 2004

ISBN 1-877276-91-X (print)

ISBN 978-0-947522-21-6 (EPUB)

ISBN 978-0-947522-99-5 (Kindle)

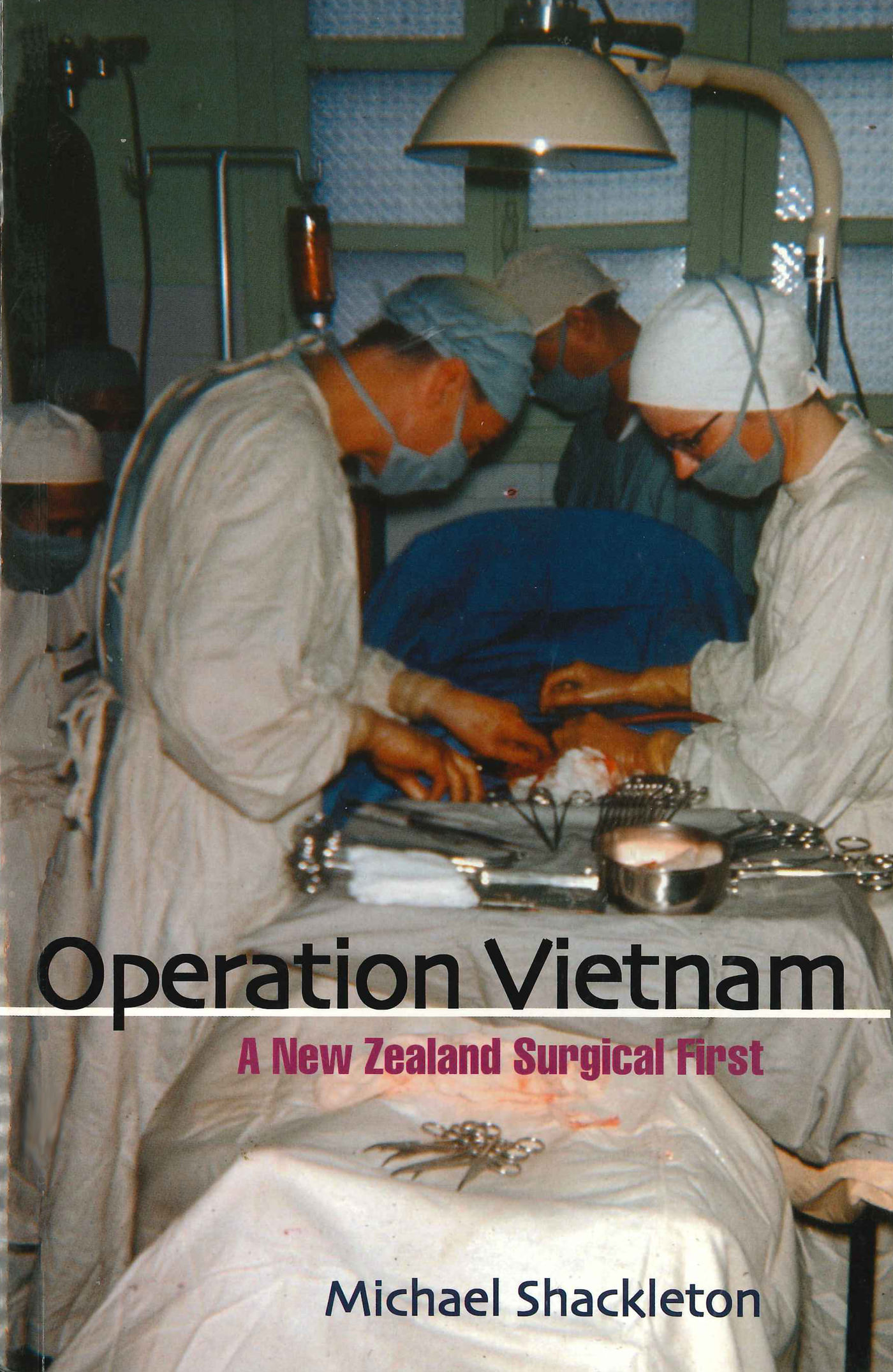

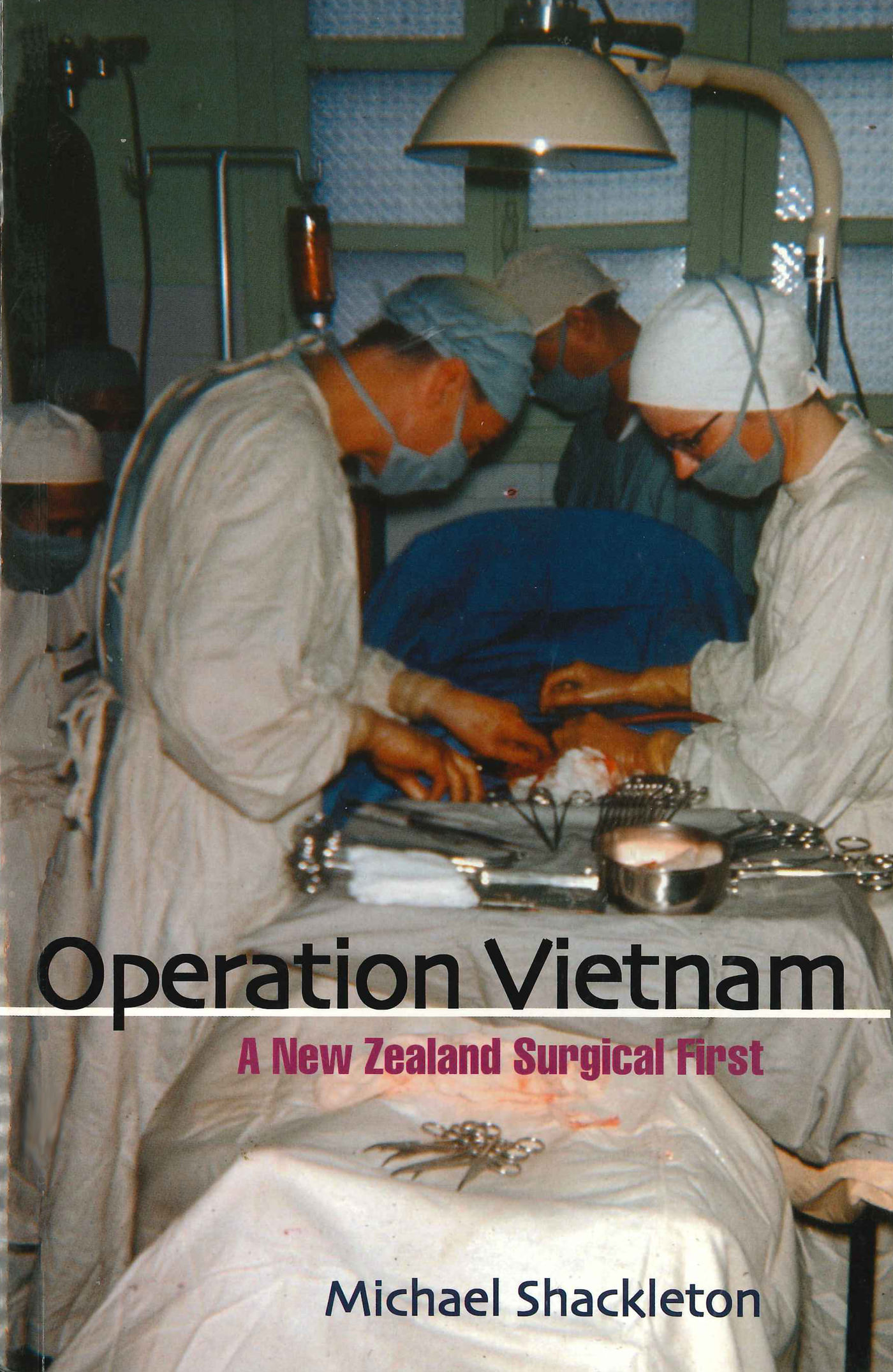

Front cover shows the surgical unit operating theatre in action the author at work assisted by Dr Sayer from the Holy Family Hospital and Dr Jacquiery as the anaesthetist, 1963.

Back cover shows Annabel Shackleton and the family on the steps of Capitol House. From left to right: Sarah, Anna, Richard, Andrew and Nicola.

Ebook conversion 2018 by meBooks

T he Vietnam war induced an unprecedented level of controversy and division in New Zealand society. The members of the armed forces who served in that war did their duty as required because service personnel volunteer only once and that is when they enlist. However, there were those other than military who responded to the request of the elected government of the day and went to Vietnam where they served with honour and distinction. Many of these people were health professionals.

Michael Shackleton, who had not long returned from his postgraduate surgical training in the United Kingdom, was invited to lead the New Zealand Surgical Team that would work with the Binh Dinh Province Hospital in the city of Qui Nhon, a challenge that he accepted.

That this team was able to work and to flourish from its inception in 1963, right up until the very last days of the war in 1974, and provide efficient and effective health care for the civilian sick and war wounded throughout the entire period, is a reflection of Michael Shackleton's dogged persistence and leadership skills as he was required to confront and deal with so many unforeseen difficulties that presented in those early days as the unit was being set up.

This odyssey, for that is what it truly was, was shared by Michael's wife, Annabel, and their five young children; Ron Mackenzie, who was in charge of the laboratory services; his wife, Shirley, and their four children; the nurses Mary Mackay and Betty Forgesson; and Dr Trevor Jacquiery.

Annabel Shackleton's contribution to this book provides vivid yet understated descriptions of the problems and anxieties that have been the lot of all wives and mothers who have had to live and survive in war zones.

The book also serves to highlight the penchant for governments to commit such teams to conflicts, and then fail to provide well-planned, adequate logistic and administrative support for them.

It also makes an important contribution to the historical record of long and honourable involvement of the health service personnel of New Zealand to wars and disasters around the world that date as far back as the Boer War at the end of the nineteenth century.

I strongly recommend this book to all those who served in Vietnam in whatever capacity, and to the rest of the New Zealand community as it illustrates the humanitarian side of our national contribution to conflict.

Brigadier B. T. McMahon

CBE, MBChB, Dip Obst, DTM&H, DPH,

Dip Ven, MRNZCGP, MCCM, FAFPHM

Formerly DGMS New Zealand Armed Forces

March 2004

M y grateful thanks to Gordon Parry whose early advice and criticism did not fall on deaf ears, to Patricia Morrison, Brian McMahon, Ron Mackenzie, David Elworthy, Terence O'Brien and Robin Charteris for comment and help, to Brian Lendrum for permission to quote from his correspondence, to Jenny McMahon and the University Photographic Services for processing the photographs and to Wendy Harrex of the University of Otago Press for patiently dealing with my impatience. My typists, Paula Watson and Susan Brinsdon, coped so well with my handwriting and dictation.

I am particularly grateful to my wife, Annabel, for her encouragement and criticism; the extracts from her letters add a significant personal dimension to the story.

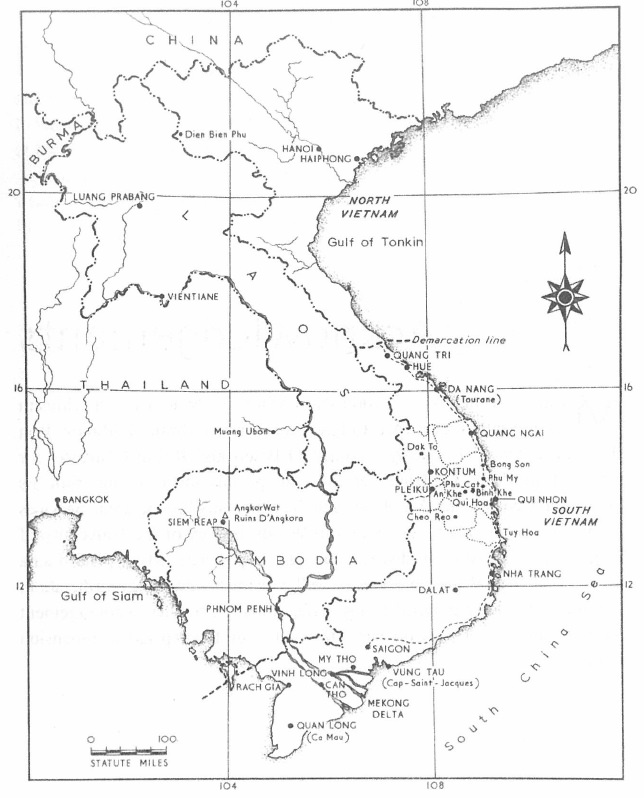

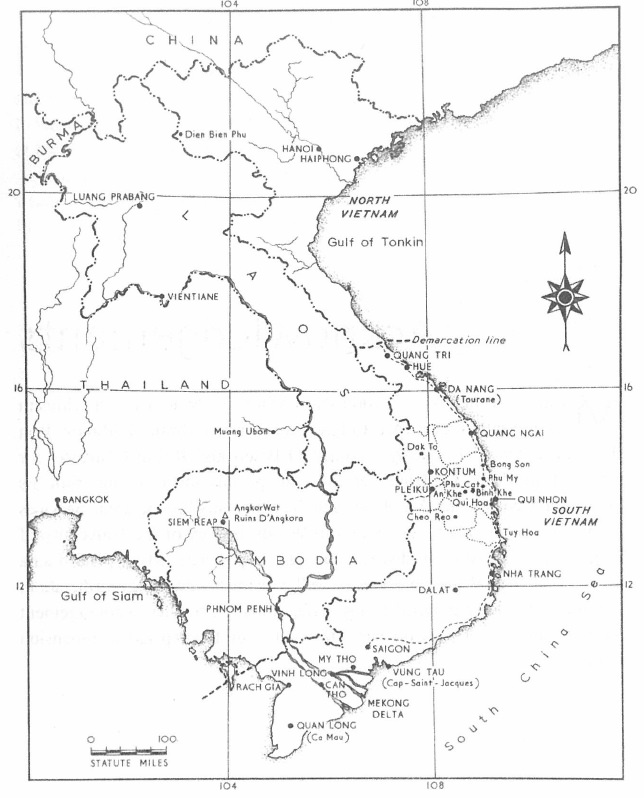

South-East Asia in 1963. (United States Information Service (USIS), 1963.)

T he year was 1963, a momentous and defining one for the USA and for Vietnam, with the overthrow and murder of Diem and his brother, Nhu, and three weeks later the assassination of President Kennedy. The two events were to have a profound effect on the people and the politicians of America and South-East Asia for the next twelve years and beyond. In that context, the establishment of a New Zealand Surgical Unit in South Vietnam in the same year, 1963, may seem a very minor segment of history, but it represented a significant contribution by New Zealand which lasted until the American withdrawal in 1975. For us and for the other members of the pioneer team it was a major event in our lives: it influenced our subsequent careers, and gave us some appreciation of the major conflict that evolved in Vietnam. There are, I hope, some aspects of this very personal story which will be of interest in giving an insight into the peculiarly New Zealand way some diplomatic policies were conducted and the equally distinctive way it could all somehow be made to succeed.

In a letter dated 12 June 1962, from the Secretary of External Affairs, A. D. Mcintosh, to the Minister of External Affairs, the Right Honourable K. J. Holyoake, a proposal for the provision of medical units for South Vietnam was outlined (see Appendix 1). The Americans had made the first approach in May when they indicated they were building and equipping surgical units at hospitals sited in the provincial capitals. Because the Vietnamese were unable to staff these units, it was hoped foreign medical teams could help. The teams would work for the benefit of the civilian population and be under the direction of the Ministry of Health, South Vietnam. It was further proposed that this assistance could be given under the Colombo Plan as the basis for some Vietnamese involvement, while payment of salaries, fares and allowances would be undertaken by New Zealand as the donor nation.

The ANZUS pact signed in 1951 formed a major part of New Zealand's defence policy and overseas political allegiance. The USA was to be our protector from communist aggression, replacing the British connection with South-East Asia, which became so diminished after the fall of Singapore in 1942. It was through the ANZUS Council, which Prime Minister Keith Holyoake had attended early in 1962, that the Americans broached the medical team concept. The other important segment of New Zealand's overseas commitment was the Colombo Plan, set up in 1950. Originally a Commonwealth partnership, it was later broadened to include the USA, Burma, Thailand, and Vietnam, along with other Asian nations. The aims were an improvement of living conditions in underdeveloped countries by providing economic assistance, to prevent, if possible, the growth of communism.

This in essence was the starting point for one of the most ambitious aid projects undertaken by New Zealand up to that time. It was to be an up-front practical commitment from the smallest partner in ANZUS to come to the assistance of the largest and most powerful partner: a real demonstration of solidarity, and not too outlandish in its scope. Or so it may have seemed to the original organisers from the External Affairs Department. The formula proposed by the Americans for the team composition was a surgeon, a general practitioner, two nurses, a lab technician, and an anaesthetist. I was not involved in the initial recruitment of the team, most of whom were either out of New Zealand or already nominated. Our family's participation was in the nature of a rescue package when the original surgeon became unavailable at the last moment. It explains, in large measure, why our departure became such a precipitate affair, and our physical and mental preparation condensed into a few days of hectic activity. We had time to read, with only partial comprehension, two articles which had appeared in the