Title Page

T hose Who

Passed By

Eleanor Turnbull

Durham, NC

Copyright

Copyright 2017 Eleanor Turnbull

Those Who Passed By

Eleanor Turnbull

Edited by Laura Brown

lightmessages.com/eleanor-turnbull

eturnbull@lightmessages.com

Published 2017, by Light Messages

www.lightmessages.com

Durham, NC 27713 USA

SAN: 920-9298

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-61153-236-4

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-61153-237-1

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017908194

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 International Copyright Act, without the prior written permission except in brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Scripture quotations are taken from the Holy Bible , English Standard Version, the Holy Bible , International Standard Version, or the Holy Bible , King James Version.

Dedication

To those who passed by,

to those who stayed,

and to those who served

Preface

The House by the Side

of the Road

There are hermit

souls that live withdrawn

In the peace of their self-content;

There are souls, like stars, that dwell apart,

In a fellowless firmament;

There are pioneer souls that blaze their paths

Where highways never ran;

But let me live by the side of the road

And be a friend to man.

Let me live in a house

by the side of the road,

Where the race of men go by

The men who are good and the men who are bad,

As good and as bad as I.

I would not sit in the scorners seat,

Or hurl the cynics ban;

Let me live in a house by the side of the road

And be a friend to man.

I see from my house

by the side of the road,

By the side of the highway of life,

The men who press with the ardor of hope,

The men who are faint with the strife.

But I turn not away from their smiles nor their tears

Both parts of an infinite plan;

Let me live in my house by the side of the road

And be a friend to man.

I know there are brook-gladdened

meadows ahead

And mountains of wearisome height;

That the road passes on through the long afternoon

And stretches away to the night.

But still I rejoice when the travelers rejoice,

And weep with the strangers that moan,

Nor live in my house by the side of the road

Like a man who dwells alone.

Let me live in my

house by the side of the road

Where the race of men go by

They are good, they are bad, they are weak, they are strong,

Wise, foolishso am I.

Then why should I sit in the scorners seat

Or hurl the cynics ban?

Let me live in my house by the side of the road

And be a friend to man.

Sam Walter Foss

Preface

I lift up my eyes toward the mountains

from where will my help come?

My help is from the Lord,

maker of heaven and earth.

Psalm 121

A s the plane descended through the clouds, the U-shaped bay of Haiti unfolded before me like a stage. A scene of tranquility met my eyes as the clouds lifted and I saw the small boats sailing in the harbor of Port-au-Prince, tiny against the looming backdrop of high mountains. Only as the light became brighter could I see that the boats sails were torn and patched and that the heavy, awkward, hand-made cargo vessels were over-loaded with sacks of charcoal, sea salt, and passengers. The smaller boombas , hand-made canoes from hollowed-out trees, carried a single fisherman using throw nets and Z-shaped bamboo fish traps to raid the waters of its already fast-diminishing life.

When I stepped onto the Haitian stage, I stepped around half-room-size piles of rotting garbage, crowded shanties, street beggars, and vertical layers of bustling human life, all telling the story of the intense struggle to survive. My senses were overwhelmed by the smells and sounds: roaring diesel trucks, constant horn blowing, and jackhammers taking out the last chunks of broken cement on Main Street.

Through all of thisand maybe because of itI kept looking upward and towards the backdrop. Just to the right was a white limestone cliff reaching into the blue tropical sky. I had to tilt my head backward to find the top of the immediate mountains and then tilt even further backward to see the more distant ranges. This backdrop gave reality to the often-repeated proverb, deye mon gen mon . Behind mountains there are mountains.

I immediately felt overwhelmed. I was twenty-three years old with a Masters Degree in Christian Education, and until that day in 1947, Id had no exposure to the extreme poverty found in the developing world. God had chosen Haiti as my mothers mission field, and I was there to check in on her before embarking on the mission I thought God had for me: flying bush planes in Africa. As I walked, I thought, The situation here is too much. There is so much to be done. Where does one begin? How does one begin?

When my eyes saw the little metal sign ROUTE KENSCOFF, I did not realize God was answering my question. I was not looking for my husband, my life, nor my ministry, but God would have me find them all.

That first day as I traveled in a tap-tap on the Kenscoff Road, it was a slippery, muddy mess of clay. Red, dirty water went rushing downhill, carrying rocks and trash in its turbulent flow. We passed masses of people moving in and out. A large group of bare-footed women carrying heavy loads on their heads gathered under an over-hanging cliff, and I heard them chattering in Creole as they readjusted their heavy loads of fifty to eighty-pound baskets with a few live chickens tied to the outside. Through my open window, I also heard a shrill Morse-code-like trumpeting I later learned was the sound of a conch-shell horn announcing community news across the mountains.

Taking in the natural beauty and awesome scenery, I was mystified. There was a feeling of isolation intensified by a language understood only by nationals, and a rural, sometimes impassable, countryside; yet the people expressed such a warmth in their boisterous expression of social happiness and obvious pride, my soul reached out to them.

The Kenscoff Road was the way that these people, the mountain population, those considered inside and isolated, traveled to the outside. The life of the inside people was busy with carrying water from whatever source was available for the familys use; foraging bits of sticks and stalks for cooking; eking out an existence from eroded, steep mountain plots; gathering Pois Congo beans; or pounding grain with a giant-size mortar and pestle. Outside was the mountain peoples term for far enough out of the mountains to see metal-roofed houses, vehicles (jeeps and trucks) and people of lighter color. The road was being built under the supervision of the United States Army Corps of Engineers. Already, the outside was reaching the inside of Haiti, and soon the hope, for my mother, and later for myself, was that the road might be a means for the Haitian people to encounter the Light of Christ and be transformed forever.

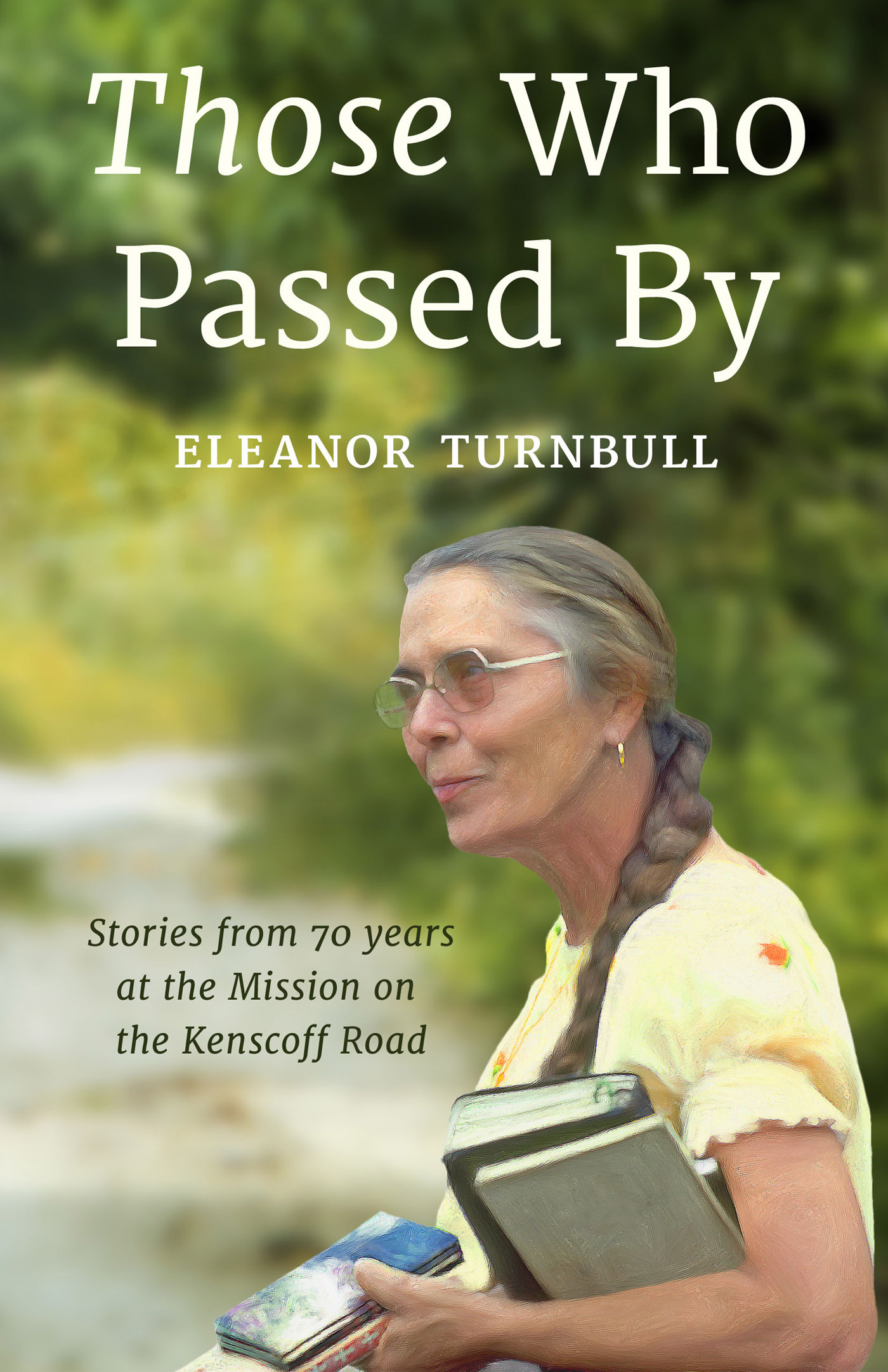

On that warm day when I arrived, Mission staff was only my mother and a twenty-two-year-old young man named Wallace Turnbull. It soon became apparent that I was one of those who passed by and had been sent to the Mission because shortly thereafter Wallace and I were married. I stayed at the Mission on the Kenscoff Road for seventy years. I was so sure the plans I had for my life were Gods plans, but in reality, my life was Gods business, and I had to get out of the way.