The moral rights of the authors have been asserted.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of New Zealand. This book is copyright. Except for the purpose of fair review, no part may be stored or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including recording or storage in any information retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. No reproduction may be made, whether by photocopying or by any other means, unless a licence has been obtained from the publisher.

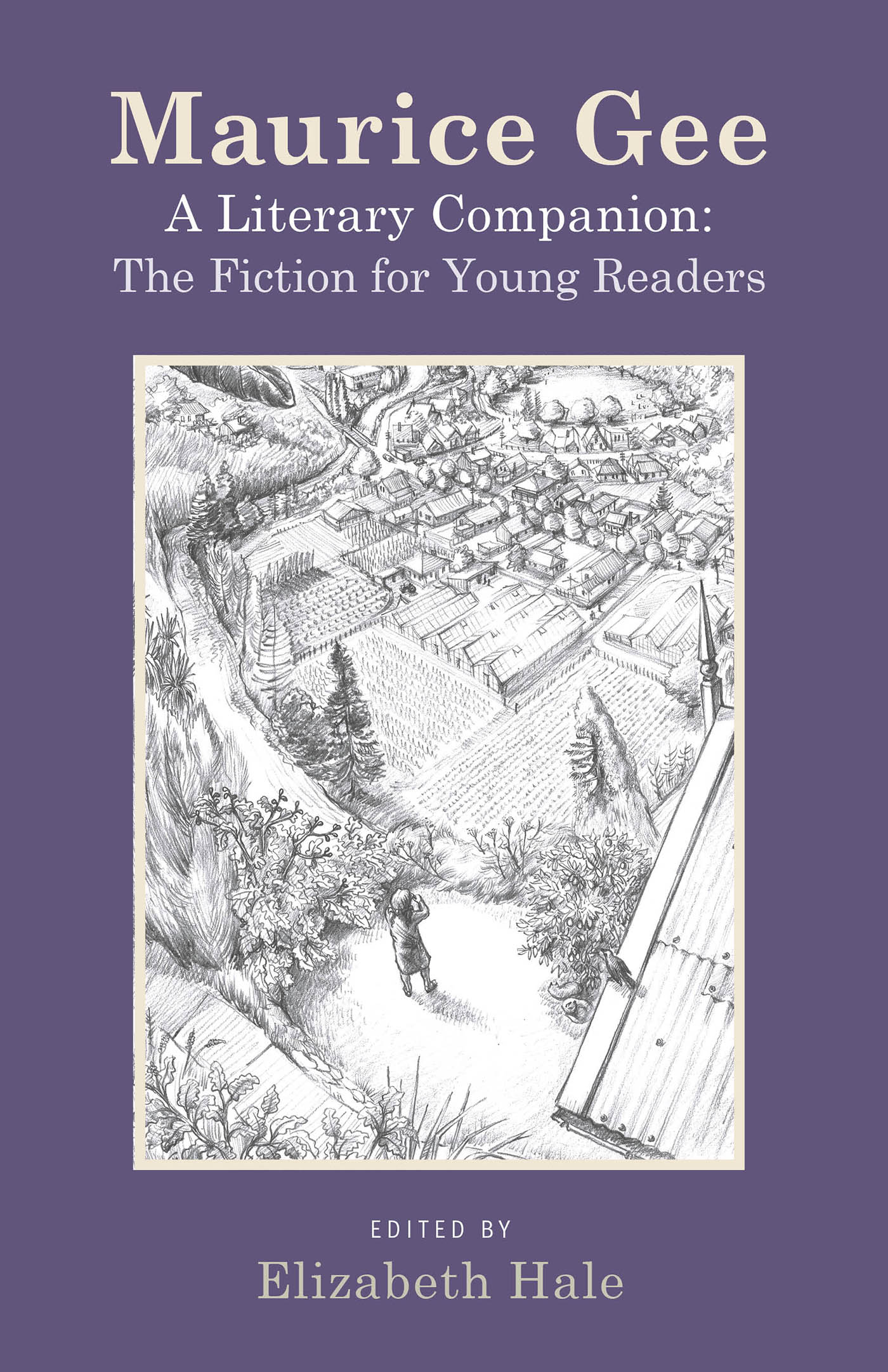

Front cover: Nelson, the centre of New Zealand from a drawing by Gary Hebley for The World Around the Corner (1980)

EDITORS NOTE

Maurice Gees first published story, The Widow, appeared in Landfall in September 1955; his final novel for adult readers, Access Road, appeared in 2009 and in his final novel for young readers, The Limping Man, in 2010. In those years Gee has gained almost every honour that New Zealand society can bestow on a writer of fiction for adults: the Robert Burns Fellowship, the Literary Fund Scholarship in Letters (twice), the Literary Fund Award for Achievement (twice), the New Zealand Book Award for Fiction (four times), the Goodman Fielder Wattie Book Award (twice), the Montana New Zealand Book Award for Fiction and the Deutz Medal (twice), the Victoria University Writing Fellowship, the Katherine Mansfield Memorial Fellowship, an inaugural New Zealand Icon Award from the Arts Foundation of New Zealand, the Prime Ministers Award for Fiction, an honorary doctorate from the University of Auckland, and the inaugural Honoured New Zealand Writer at the 2012 Auckland Writers and Readers Festival.

Trevor James, who has written some of the most interesting and enlightening criticism of Maurice Gees adult fiction, remarked in 1998 on the huge gap where one would expect to find a body of critical discussion of Gees work, and speculated concerning the cause:

The relative lack of attention Gee has received from literary critics in New Zealand marks a huge gap in New Zealand literary criticism; certainly he has received far less than his stature as a writer deserves, and I suspect that this reflects the influence of literary fashion. Though Gee has been consistently praised by reviewers, the realistic surface of his fiction appears the most likely deterrent to more sustained and rigorous critical attention.

This book is the first in a two-volume series discussing the fiction of Maurice Gee. Over a career that spans 55 years so far, Gee has published 17 novels and more than 20 short stories for adult readers, and 13 novels for younger readers. These fictions create a variety of worlds. Denis Welch, in reviewing Gees sixteenth novel for adults, Blindsight, in 2005, made a case for looking at all of Gees fiction written for adults as creating a single, evolving fictional world, Geeland: a country of the mind that novel by novel has taken shape in our literary consciousness,

The fiction for younger readers, however, ranges much more widely. The five realist historical novels, published at irregular intervals between 1986 and 1999, take place in a somewhat simplified but recognisable version of Geeland. The eight other novels for younger readers, however, have at least elements of alternative worlds. The first, Under the Mountain (1979), takes place in the Auckland of Geeland, but aliens from two different planets infiltrate and influence it. In the second novel, The World Around the Corner (1980), Nelson (Saxton or Jessop in Geeland) has within it a gateway to the alternative world of the title. The novels of the O trilogy (198285) are likewise gateway books in which the movement is from the fictionalised Golden Bay to the alternative world of O and back. Finally, the Salt trilogy (200710) takes place entirely within a self-contained alternative world.

These two quite different but related bodies of fiction Gees writing for adults and his writing for young readers are subject to different critical approaches in this two-volume series. Lawrence Jones, who has been writing and publishing on Gees work for almost 40 years, constructs his text as a chronological narrative tracing, through close and contextual readings of all the works written for adults, the development of Gees vision of a changing New Zealand and his narrative means for presenting it. In the present volume, Elizabeth Hale, who has previously co-edited a collection of essays on the fiction of Margaret Mahy, decided on an approach that blends the chronological with a consideration of genre and topic.

The two volumes in this series discuss all of Gees published fictions, from The Widow in 1955 to The Limping Man in 2010. They present all of Gees fictional worlds, from twentieth-century and early twenty-first-century New Zealand to the post-apocalyptic world of the Salt trilogy. Our hope is that these two volumes will be a useful companion in the readers exploration of the worlds created by one of New Zealands finest writers.

Lawrence Jones

and Elizabeth Hale

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

In late 2005, at a morning tea in the English Department at the University of Otago, Lawrence Jones told me he was working on a book on Maurice Gee. Oh, I said, well, if you want anything on the childrens literature, let me know. The next day he wrote to me suggesting I take over the section on the childrens literature, and I happily agreed. It has been a somewhat longer journey to publication than we anticipated; what was conceived of as a single book has become two: this current volume, and Lawrences volume on Gees fiction for adult readers to follow. My main acknowledgement is therefore to Lawrence, whose scholarly dedication to the literature of New Zealand is second to none. It is a privilege to be associated with him, and to be part of a project devoted to the remarkable writings of Maurice Gee. It has also been a privilege to work with the contributors to this volume Claudia Marquis, Diane Hebley, Kathryn Walls, Louise Clark and Vivien van Rij whose knowledge and expertise has greatly added to the richness of the project. My colleagues at the University of New England Jennifer McDonell, David Roberts, Fiona Utley, Sascha Morrell, Susan Potter, Richard Scully, Natalia Tobin, Yvonne Griggs, Adrian Kiernander and Alan Davison have been endlessly encouraging in research discussions, and I thank them for their support. I am especially grateful to the School of Arts at the University of New England, which supported me in the research and writing of this book through research leave, travel grants and funding to support the final stages of the project. Sarah Winters of Nipissing University read earlier drafts of my chapters and I am exceedingly grateful for her sound advice. My family, particularly my father John and mother Beatrice, offered insights, wisdom, advice and support at crucial moments. Otago University Press, under the guidance of Rachel Scott and the editing of Gillian Tewsley, has been wonderful to work with. I would also like to thank Gary Hebley for permission to use his beautiful illustration from