This book is also available as a paperback.

For further information please visit:

www.vividpublishing.com.au/ifonthisearth

Aid Project of Mercy website:

www.kslkhmerlanguage.com

Copyright 2016 Seng BouAddheka / Jim Pollock

ISBN: 978-1-925442-40-3 (eBook)

EPUB Edition

Published by Vivid Publishing

P.O. Box 948, Fremantle Western Australia 6959

www.vividpublishing.com.au

eBook conversion and distribution by Fontaine Publishing Group, Australia

www.fontaine.com.au

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, printing, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner.

This book is dedicated to my parents

who loved me as long as they were able.

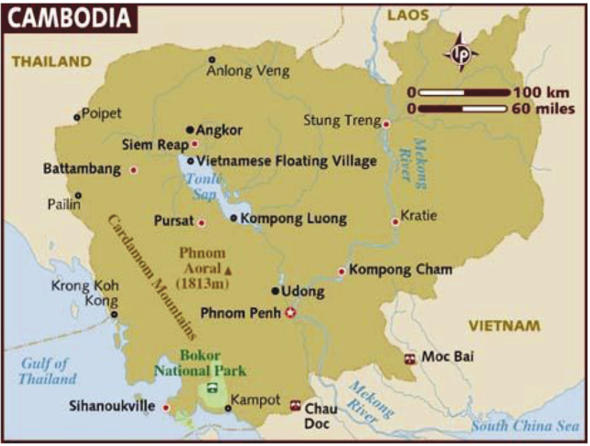

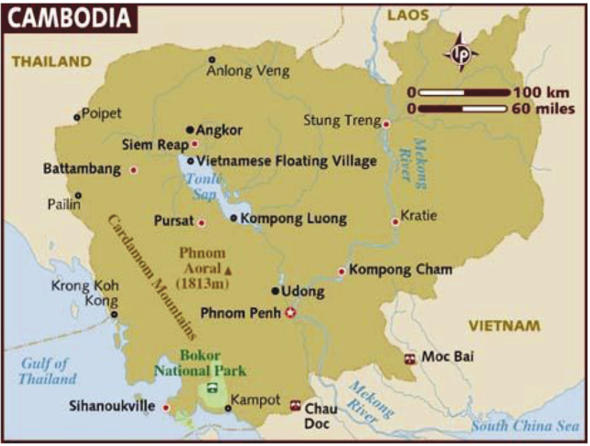

Figure 1: Map of Cambodia

(Reproduced with permission from the Lonely Planet website www.lonelyplanet.com 2011 Lonely Planet.)

Introduction

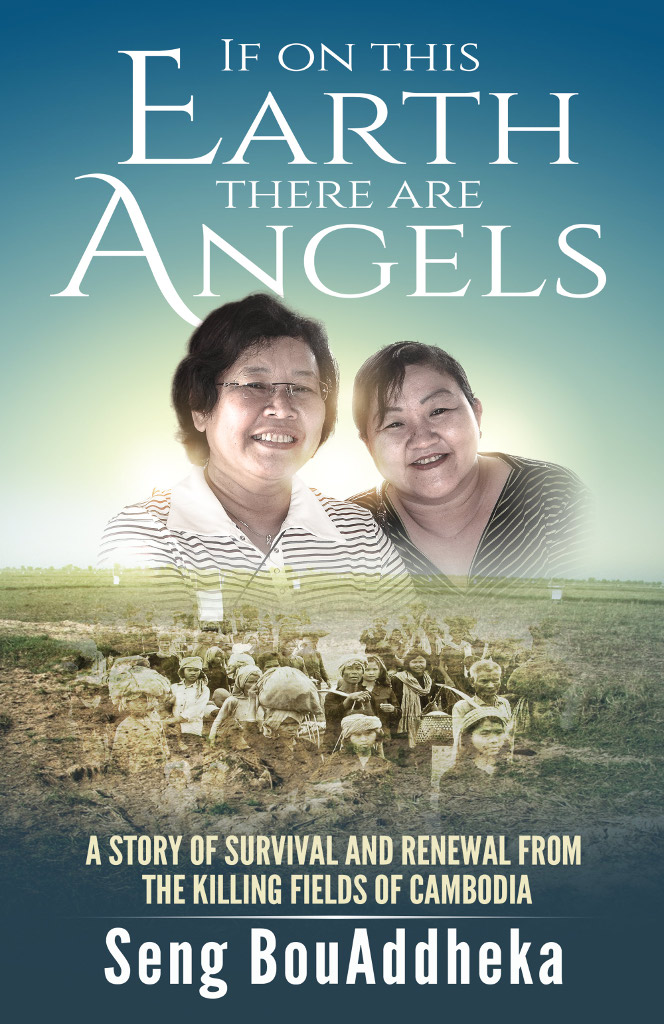

I first knew Addheka as my language teacher a voice on the other end of a Skype partnership over 12 months. I had decided to learn the local Khmer language so I could better get to know the Cambodian villagers my wife and I were helping to build houses for.

When I met Addheka in Phnom Penh I noticed she was in a wheelchair but didnt probe further. As we spent more time together, our lessons often drifted off-task as I asked her about her life. My curiosity was aroused when it became clear she had both survived the Khmer Rouge regime and been disabled since she was two years old. There was also an aid project her school seemed to be involved with.

A year later I was studying with her at the KSL (Khmer School of Language) in Phnom Penh and we came to know more about each other. Once or twice we had to take a break, as her emotions overwhelmed her when reflecting on her life as a disabled person and things that might have been.

At some point I remarked that she should write her story. She told me she already had thanks to enforced idleness when she broke her leg in 2009 but turning this into a book would require some assistance. Was I interested in helping her with this endeavour?

Over the next 18 months we spent many hours talking, mainly online using Skype but also in Cambodia, where we visited the places that held her story. We went to the flat rice fields of Cha Huoy, to the banks of the Mekong River in Prek Eng and to the pagoda in Touk Meas where her family still remembers those departed. She introduced me to many of the people with whom she has crafted a life after the unimaginable horrors they all lived through under Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge.

The most crucial moment in the story of this book came when Addheka told her older sister, Wantha, who is ten years older, that she was writing the story of their lives. I learnt that these two Cambodian women, so close for so long, had barely talked about the Pol Pot times since the nightmare ended. Addheka did not know if Wantha would approve of their story being told.

There was more to this than having to re-live the suffering and loss under the Khmer Rouge regime, though that was significant enough. There were skeletons in the family cupboard and Addheka was going to reveal them. In turn, this could have an effect on the other family members who had also survived the Khmer Rouge and were still alive.

Wantha gave the project her blessing, knowing that it was her younger sisters deep desire to share her remarkable and inspiring story with anyone who was interested. Reluctantly initially, Wantha allowed herself to be quizzed by me on details that Addheka either did not know about or had hazy memories of.

Seurn, an older cousin and dear friend of the two women, also allowed himself to share some details of Addhekas story. For all three, the past is so painful to recall, the losses so profound. It is my great hope that in some way their involvement in this project may prove to be cathartic.

Addheka also introduced me to some of the 600 children and their families from all over the country that she helps. The selfless, hands-on support she provides each weekend is a testament to the depth of her spiritual beliefs and sense of purpose. She has done this for nearly two decades.

Jim Pollock,

co-editor December 2015

Preface

I often describe my life as being of three parts. My first life was full of family and connections to life around my home in Phnom Penh. I was one of 25 full and half siblings, a testament to a father whose ambition spawned three families. Growing up I knew nothing else and never wanted for company.

I couldnt walk until I was 13 years old as I contracted polio at the age of two. School for me was something to savour, and just to be there was all I asked. I could read better than most of my peers so I knew this thing called education was going to be part of my world.

My first life, with parents, love, learning and freedom ended on 17 April 1975 with the takeover by the communist Khmer Rouge regime, led by its brutal, secretive leader, Pol Pot.

As we trudged out of Phnom Penh, herded along by the young, hate-filled, rifle-toting militants, I had no idea what was about to happen. A darkness descended on our lives that extinguished everything that made life worth living. My life spiraled downwards into isolation and depravity I could never have imagined possible, let alone one that I could survive. While those around me starved to death or succumbed to malaria or dysentery, I continued to see another sunrise.

In the darkest days and nights, my life could have been snuffed out without anyone noticing or caring. When the regime was swept away four years later, most found it hard to believe I had survived. How could a nave, crippled child who had known only comfort and dependence, outlive almost her entire family?

Those of my family who survived have an unbreakable bond with each other. I renew their fellowship regularly and have never lived far from them. I look after them and they look after me.

Some of my family would not leave in the desperate days following the demise of the Pol Pot regime because of me. My immobility made it impossible for them to consider risking flight. That is a cross I bear, as perhaps life may have been better for them if they had left me behind and fled then.

Since that time the greatest sadness in my life is that I cannot give back to the members of my family whose lives were lost during this period, and repay their love and care. So I find other ways to give back to show that the world is a better place for my survival, and it was not an oversight that I am still here. I care for those who need me.

I have over 600 children from very poor families who look to me when life becomes impossible. Together with the staff from the Khmer School of Language and my family members, young and old, they form the fabric of my life.

Seng BouAddheka,

December 2015

Part 1

My First Life

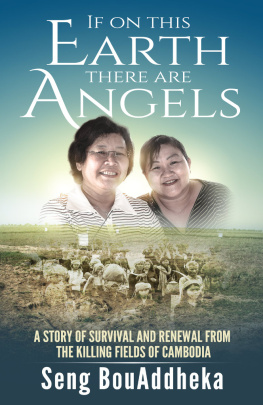

My family, taken in March 1975, from left to right: Rathya, Laddha (me), Nora, Chittra, Ratana, Wantha, Vanna, with her two sons, Kaddeka (standing) and Karuna, in her mothers arms. Sitting, Pan SutChay, my mother and Seng Bou, my father.