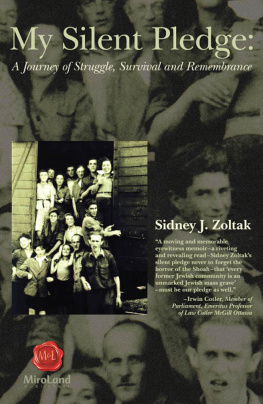

This book is dedicated

to my grandchildren,

Jason, Melissa and Matthew,

as my legacy,

and to the memory of their grandmother,

and my beloved wife of 53 years,

Ann Dickstein Zoltak

Foreword

I am myself a child who survived the Holocaust in hiding with kindly Christians in The Hague, Holland. My nearly three years with them was comparatively uneventful, without apparent danger, and filled with my hiders love and attention. Then why do I tremble to this day with the reverberations of what had happened to me between the ages of two to five? For as much as I have tried to normalize my existence in hiding, it was off the scale of normality and left wounds and scars. Every Jewish child within the grasp of Nazi Germany was a hunted child and, when caught, murdered. Ones mind cannot normalize such a situation.

Hence, when I face the memoir of a fellow child survivor, I read with trepidation, not only in fear of the memories that will inevitably surface, but with the foreknowledge that I will likely encounter an experience far less fortunate than mine. After all, if my experience was off the scale, how much more so was that of children in even greater danger and in more strenuous circumstances?

But then again, if Sidney Zoltak is brave enough to write, I shall be brave enough to read and shed some tears, inevitable tears. For that I am prepared.

A Shoah memoir is a precious document, not only for family but for all of us, our children and grandchildren. Sidney has provided a legacy that not only informs us but may protect us. For in recounting his life he enlightens us about good and evil, kindness and indifference, compassion and hatred. Evidence for all is found throughout this at times terrifying, and often, inspiring account.

Remember that, of all Jewish children under German occupation, 93% were murdered. Counting the few that were rescued before the onset of the slaughter, fewer than one in ten were able to survive. In total, one and one-half million Jewish children and adolescents perished. If that alone is beyond imagining, then let us not describe how they were killed. The killers imagination had no bounds where murder was concerned.

Sidney was a child of eight when war broke out. He grew up quickly becoming an adult in a childs body. And that body was malnourished and weakly. The Zoltaks hid in forests, barns, and dug bunkers into the ground, sometimes sharing space with a dozen people where there was no space. I know that my grandparents and their thirteen-year-old daughter (my aunt), were hiding in such a hole dug into frozen ground. They were found (betrayed?) and killed by local Poles, with axes. I shudder when I read of bunkers.

With the help of the righteous Krynskis, the Zoltak family survived. Sidney describes the consequences of survival in a thoughtful commentary on luck and guilt after liberation. And everywhere there are hints that children contributed to their luck through their silence and co-operation, their facility with languages, their suppression of grief and tears despite enormous losses. But, for most, that proved not enough.

For children of the Shoah, liberation was frequently marked less by the day the war ended than the day of arrival in the new country to begin life anew. And Sidney did that with a vengeance. He already spoke Polish, Yiddish, Hebrew, Russian, and Italian. French and English posed no particular problem. Sidney studied, worked, raised a family, became a stalwart leader in his community and devoted much energy to remembering the Shoah and to advocating for Holocaust Survivors, particularly those whose lives were compromised by their experiences and who have struggled throughout life.

I urge you to take this memorable journey with the author as he re-visits his childhood town and its environs, and brings to life its tragic past, his familys sojourn in Italy and his triumphant accomplishments in his home of sixty-five years, Canada.

I also urge the reader to note his struggle with his faith and his G-D, especially when he and his dear wife Ann, also a child survivor, faced a tragedy that no parents should have to face, the loss of a son.

Ultimately, their courage, past and present, reveals them to have remained devoted to family, friends and community within their Jewish traditions. Nor did the author forget the people who shone a light in the darkness of the Shoah, a light sufficient for Sidney to have survived, when for most Jews, there was only darkness.

Read and learn. Learn that, even after survival, children were not necessarily welcomed in their new surroundings, nor were they encouraged to relate their stories. Theirs were not considered important enough. After all they were too young to have suffered or to have memories. In many ways, they were silenced, ignored, and sometimes humiliated. I remember it well. The Holocaust did not end for us children. The Zoltak memoir reflects the postwar struggle, its good moments as well as its difficulties. But the authors achievements are noteworthy and inspiring, an admirable journey. I am so proud to know him and so grateful for his wisdom.

Robert Krell, M.D. F.R.C.P.(C) A.B.P.N.

Professor Emeritus, Department of Psychiatry

The University of British Columbia

Distinguished Life Fellow

American Psychiatric Association

Prologue

In September of 1997, I find myself on a journey I had vowed never to make. It begins with my wife, Ann, and me boarding a plane in Montreal for a flight to Warsaw, Poland. Our son, Larry, will leave later that evening on another airline and meet us at the airport in Warsaw.

The last time I was in Warsaw, I was eight years old. It was the summer of 1939.

We are joined by seven other members of my family at the hotel in Warsaw. Arriving from Israel are my cousin, Chana Broder, her husband, Tashie, their son, David, and cousin, Shosh Bentman, and her husband, Yigal. My stepbrother, Simon Braitman, and his wife, Josephine are coming from Rochester, N.Y.

Together, our band of ten has planned a harrowing four-day journey into the past. It begins with a return to my hometown of Siemiatycze (Semiatych in Yiddish) and then, on to other sites in Poland, mostly concentration camps that were part of the Nazis murdering industry. These death factories were created and run by the German Third Reich with the enthusiastic and willing assistance of many people in Poland and neighbouring nations.

Before the war, the Jewish community of Siemiatycze had existed for 400 years. What I remember of my town is that, before September 1939, it was full of proud Jews who had created a vibrant and compassionate society of high ideals. In the summer of 1944, after liberation, when my family and I returned to our town, we were treated like strangers, like outsiders, by the Poles we encountered.

After the war, when someone recognized one of their former Jewish neighbours, they would ask: You are still alive? This question openly demonstrated that they did not want us coming back. Some went so far as to murder without consequence a few of the returning Jews. This scared the rest of us sufficiently and forced us to flee the only home we had ever known.

Some 52 years earlier, as my parents and I left Poland, I had vowed never to return to my birthplace. Yet, here I am.

What has led me to change my mind? Why have I returned to visit this place of hatred, death and destruction, this place I once called