Classic Cinema.

Timeless TV.

Retro Radio.

BearManor Media

See our complete catalog at www.bearmanormedia.com

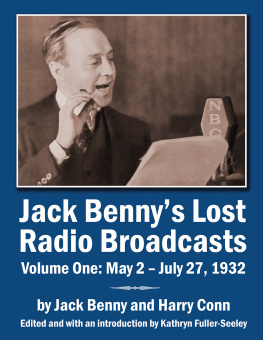

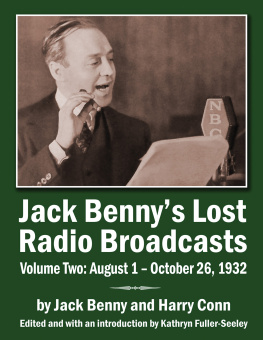

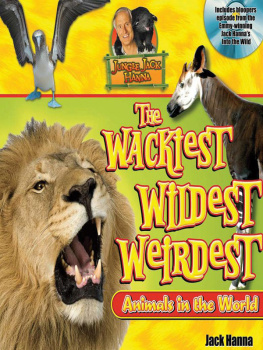

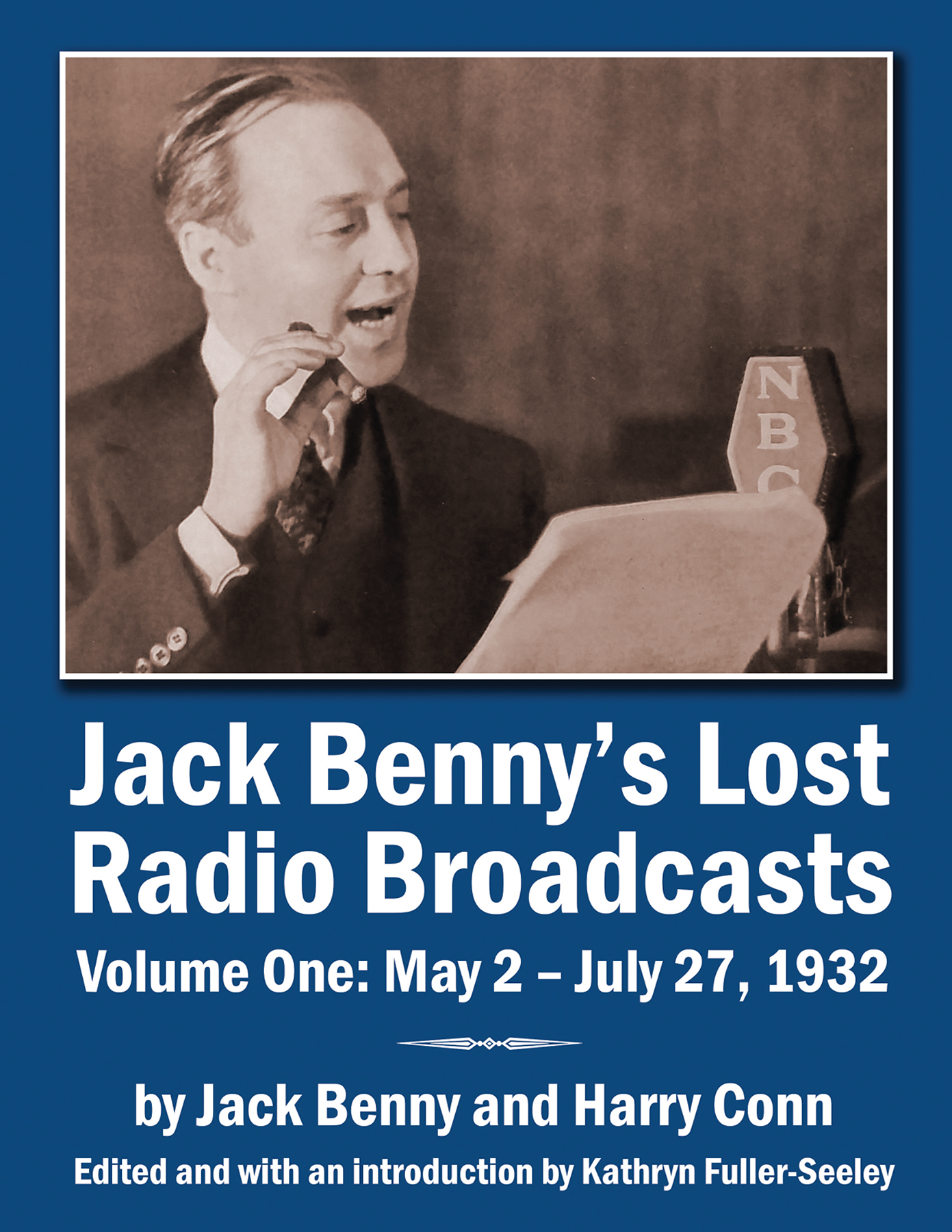

Jack Benny's Lost Radio Broadcasts: Volume 1, May 2-July 27, 1932

by Jack Benny and Harry Conn

Introduction 2020 Kathryn Fuller-Seeley. All Rights Reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, digital, photocopying or recording, except for the inclusion in a review, without permission in writing from the publisher.

This version of the book may be slightly abridged from the print version.

Published in the USA by:

BearManor Media

1317 Edgewater Drive #110

Orlando, Florida 32804

www.bearmanormedia.com

ISBN 978-1-62933-578-0

Front cover illustration: Young and Rubicam advertisement, Fortune, June 1935

Cover Design by John Teehan.

eBook construction by

Introduction

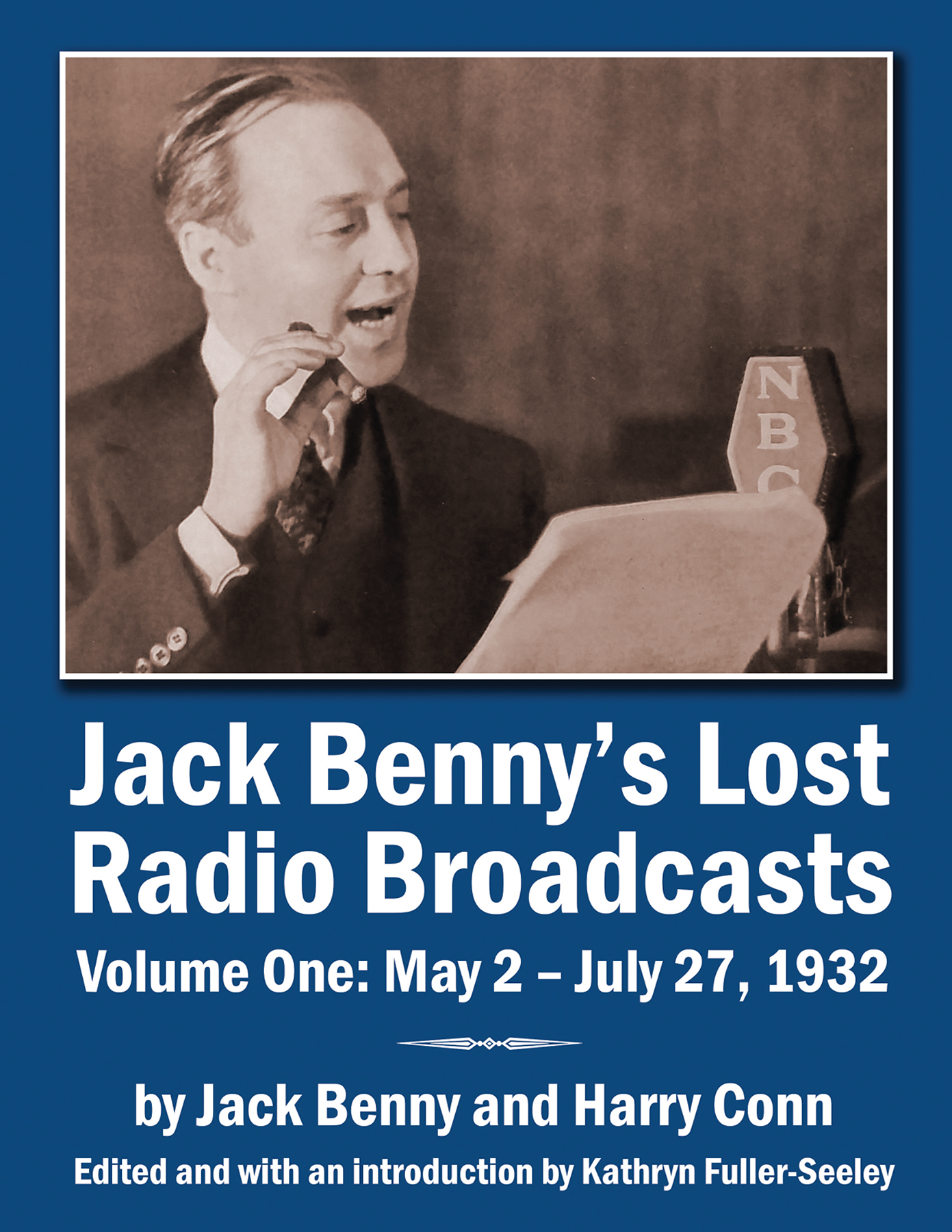

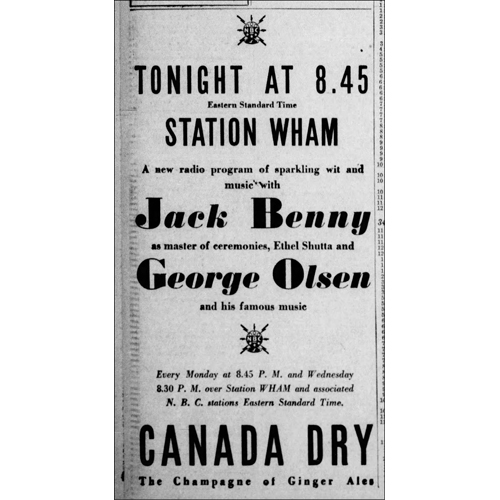

Jack Benny, radios greatest comedian, broadcast 931 half-hour episodes of his program between 1932 and 1955. His show is renowned for the character Benny created the eternally 39-year old fall guy, the vain cheapskate who was constantly the butt of jokes launched by his zany cast of underlings announcer, bandleader, tenor, quasi-secretary and valet. The ancient Maxwell jalopy, the vault, the shows catchphrases and running gags are dear to all who love old-time radio. Yet Bennys comic world did not launch fully formed when he began his NBC program on May 2, 1932. Originally billed as the Canada Dry humorist, Bennys initial duty was to provide brief monologues between six tunes performed by prominent New York bandleader George Olsens musicians and sung by his wife, Ziegfeld Follies chanteuse Ethel Shutta.

How did Jack Bennys program evolve from stand-up routines to lively ensemble situation comedy? For nearly 90 years, it has been very difficult for radio fans to learn. Of the first five seasons of live broadcasts, 177 episodes have no available recordings and many of the remainder are only fragmentary or in poor shape. Most of the fragile transcription discs of the episodes that Benny received have decayed over the years.

I am delighted to present the scripts of these early lost Jack Benny radio programs, transcribed from the originals housed in the Jack Benny Papers, in Special Collections at the UCLA library, for your reading pleasure. Of the 26 scripts presented here, only a recording of the first episode (May 2) is known to exist. Indeed, four of these scripts were missing from Jack Bennys own collection, including the most significant one which introduced the Mary Livingstone character to the show. Fortuitously, they have been located in the NBC Masterfile collection at the Library of Congress, and are included.

The Earliest Episodes

The Canada Dry Program, featuring Jack Benny, George Olsen and Ethel Shutta (pronounced shu-TAY) , debuted on Monday May 2, 1932 at 9:30 pm Eastern time on the NBC Blue network. Broadcast twice a week (Mondays and Wednesdays) the program was produced in a small-glass-walled studio that NBC had erected in the former Roof Garden of the New Amsterdam Theatre in Manhattan, that had been home to Ziegfeld summer midnight shows in the 1920s. No studio audience added laughter and applause to the live broadcasts.

The show had been assembled for Canada Dry Ginger Ale by NBC executive Bertha Brainard as a new direction in sponsorship for the company, which had previously underwritten a dramatic (and violent) adventure series set in the Canadian Rockies. Advertising agency N.W. Ayer & Son billed the new show as 30 minutes of music and quips featuring Olsen and Shutta. Already widely familiar to radio listeners, they were considered to be the main attraction. The music would be interspersed with brief monologue segments performed by 38-year-old Jack Benny, a Midwestern-voiced, genially-self-deprecating vaudeville veteran known around New York as that sleekly bored joker and a Broadway Romeo.

Neither Brainard nor the admen were not especially enthusiastic about the choice of Jack Benny. They were uncertain about what styles and types of performers would work on the radio some preferred the loud brashness and quickness of other comics and the stentorian tones of tuxedoed announcers. NBC had actually approached literary humorist Irvin S. Cobb prior to contacting Benny, but Cobbs salary demands were too high. Executives probably noted the affinities Bennys vaudeville act had with aural presentation Benny produced most of his humor through low-key language and smooth, superbly timed delivery of his lines. He was not a primarily physical or visual comedian getting laughs through broad facial expressions, costume, or slapstick body movements. Benny engaged in quiet, intimate joking, confiding in the audience as if it were a small group, similar to the methods of popular crooning singers Bing Crosby and Rudy Vallee. On the other hand, Bennys droll stare out at the vaudeville audience, with hand to his cheek, which silently communicated his frustration and won viewers sympathy, would be lost on radio listeners. (It would only reemerge in the early 1950s to embellish his comedy routines on television.)

The new Canada Dry show joined a rapidly increasing number of variety-comedy programs on primetime network radio. While music had been the dominant program form of the previous five years, the entertainment trade press noted that comedy was growing as a less expensive option for sponsors weary of paying for high-priced orchestras and temperamental crooners. New shows in the 1932 season featured not only newcomer Jack Benny but also other vaudevillians such as George Burns and Gracie Allen, George Jessel, Fred Allen, and Jack Pearl. The new entrants joined such already-popular variety programs as those hosted by Rudy Vallee for Fleischmanns Yeast, Ed Wynn for Texaco, and Eddie Cantor for Chase and Sanborn Coffee.

As Benny began the twice-weekly broadcasts of Canada Drys new musical comedy radio show in May 1932, it seemed that not only he, but the sponsor, ad agency, and network were almost shockingly nave about how much labor Bennys role might entail. The orchestra and vocalist had large musical catalogs from which they could draw new tunes to perform, but if Benny was to do more than introduce the title of the next song, he was going to need fresh material every episode. The executives must have assumed Benny ad-libbed or wrote his own humorous asides. As a popular emcee, Benny had experience in creating short gags and exchanges with vaudeville performers, but he was used to repeating similar patter for different audiences the whole week of the engagement, either getting new performers to work with or a new city to play in the following week.

The first live Canada Dry episode demonstrated the promise and the drawback of the concept. In seven short monologues interspersed between the songs, Benny presented himself as a suave, urban, and thoroughly Americanized fellow who was witty and personable, a wisecracker who was self-centered but who self-deprecatingly understood that his attempts at boastful egotism would end in mild humiliation. Benny exchanged a little banter with Olsen and Shutta as he introduced them. Nervous awkwardness of the new endeavor was apparent in Bennys doing most of the talking and their very brief responses to standard vaudeville jokes, such as ribbing the age of Olsens automobile. Benny always worked from a script; he wanted a written structure to guide him to make sure he was organized and that the wording of the jokes could be carefully pored over and crafted into polished gems. He delivered his lines, though, in such an easy, nonchalant manner that listeners may have thought he was speaking off-the-cuff. Even in this first episode, he wove the middle-of-the-program advertising messages into his monologues, entwining a playful (and fairly unusual) mocking tone toward the product in the same way he told self-deprecating stories about himself.