This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be made to the publisher.

Transit Lounge is a proud member of the A.P.A. (Australian Publishers Association) and S.P.U.N.C. (Small Press Underground Networking Community)

Jennys Coffee House : after Yenni / Eugenia Jenny Williams.

1st ed.

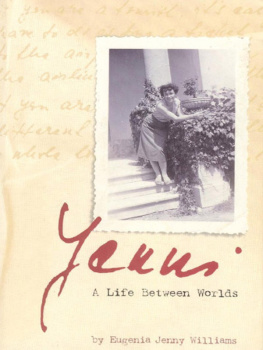

Hungarians--Tasmania--Biography.

Immigrants--Tasmania--Biography.

It was an unforgettable, heart-piercing moment to leave my grandparents, Omama and Opapa, behind. They were both in their seventies. I still feel the touch of Omamas warm, tear-drenched cheek on mine. I still feel her last kiss. My heart still aches.

I am Yenni and it was I who thought it all out. No future for us or our children in this country after the occupation by the USSR in August 1968. No prospect of keeping our jobs, no university studies for the children, no security. Only tanks with Russian soldiers sitting in turrets with their Katyuskas at the ready.

There were seven of us, four adults and three children my husband Yano, my mother, who we called Mami, my sister Chopi, six years my junior, her one-year-old son Roman, myself and our two children, Ishtvan and Zsuzsi, then aged twelve and nine. Together we illegally escaped in February 1969 from the country behind the Iron Curtain then called Czechoslovakia.

Before our departure we read the pamphlets about the Australian way of life, which were sent over from the Australian Embassy in Vienna by a friend who had already escaped. We compared the minimum wages, the housing, the schooling, the prices, the freedom. We were well informed; even worked out that after our weekly shopping of groceries, and adding some small luxuries, we would still have $5 saved from our minimum wages. Five whole dollars. What a country, I thought. And then there was Yannibachi, Omamas brother, who lived in Hobart, Tasmania, with his wife Hedineni and their daughter Nana. In their letter to us they promised to give us moral support.

But did I know what it meant to drag the whole family out of their comfort zone into emigration? Did I consider the moral and financial consequence for Mami in leaving her job as legal adviser to a large wholesale firm, for Chopi to leave her teaching position and for me to give up my position of secretary to the Invalid Committee? And Yano, who had 150 people working under him?

All right, all right, I argued, it was a big world out there with all its insecurities, unknown problems and languages, but the hardest part surely had to be to get over the border. Once we were safe in a free country things would be good. A little hardship for a short while, thats all. We are all healthy, well-meaning, hard-working people.

That belief and my ability to voice my opinion with self-confidence and assuredness helped. They all listened and believed in the picture I painted about our bright future.

One cold winter morning, with the snow weighing down the bare branches of trees and the streets looking like an enchanted fairytale, we turned the key of our flat on the second floor, closing the door on our world, the furniture, the doonas and bedsheets, coats and parkas, the porcelain, books and paintings. We carried the three suitcases, which from then on represented all our belongings, to the railway station to catch the train to Vienna, supposedly only for a few days over the school holidays. But I knew better.

A group of four uniformed men enter the carriage compartment. So, where are we going with the children? they ask.

Just visiting an aunt in Vienna.

Uh-um, they say. Two of them step back, keeping the door open, and the other two kneel on the floor looking under the seats with torches. Through the window we see men in uniforms with guns hanging off their shoulders and sniffer dogs at their heels walking on the platform. More soldiers get on the train. Another thirty minutes. When the train finally starts up my hands slide into the pockets of my skirt, searching for my handkerchief, and I wipe the pearls of sweat above my lip.

We left behind all we knew not just our belongings we left the streets we knew how to walk on, the shops we knew how to shop in, the language we knew how to communicate with, the system that we had learned to find our way in. We left behind our culture, our identity. And friends, good friends like Svetya and others.

Our future became a clear slate with no mark on it. Nothing of what we knew was of any use to us. And like a newborn we had to learn to exist.

CHAPTER

ONE

Under the aeroplane the large sheet of water is fretted, edged into small bays, and is reflecting the setting sun in long orange strips. We are losing altitude. The waves, smooth and heavy like oil, come close to the wing of the plane and the small window I am looking out of, but I am too tired to worry. The plane levels its wings and slides onto the tarmac, leaving the water behind. Hobart, Tasmania, on the other side of my old world. No more getting on and off planes and sitting in airports. After thirty hours we have arrived.

In front of a low oblong building is a group of people, some waving frantically. When the plane taxies closer I recognise Yanibachi and his wife Hedineni as I remember them from the photos on the wall of Omamas bedroom. The rest of the people I dont know.

For a second I am worried about my appearance, then begin fussing about the children, straightening their coats and shirts as we progress through the narrow passage and onto the stairs. Descending in single file, Zsuzsi wriggles herself to the front and runs across the concrete expanse towards Yanibachi. Yano follows with Roman on his arm, Isthtvan next to him, then Mami and Chopi. I am the last one to touch the Tasmanian ground. The group of people seemingly jump out of their background and become larger as we walk closer to them. It seems such a long walk to the building.