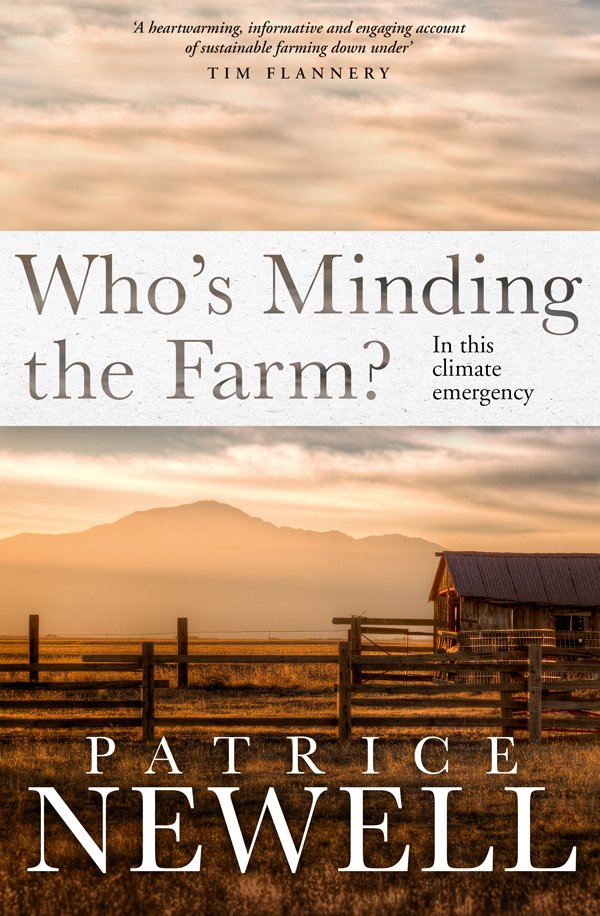

About the Book

A call to arms from Patrice Newell, who has dedicated her life to land management at Elmswood in the Hunter Valley.

In an era of rapid climate change, this vital account of how agriculture can address major issues is an Australian story with global ramifications. Patrice is at the frontline of enormous challenges, from water scarcity and land stewardship to food security and the ruralurban divide. The devastation of drought and the crises created by industrial-scale chemically dependent primary production are discussed and alternatives proposed along with bold ideas for new sources of energy.

Patrice has travelled the world exploring best practice and invested heavily in organic methods on her farm. She believes we can produce enough good food to feed the world without further environmental wreckage or loss of biodiversity. With glimpses of the individuals who make working the farm so rewarding, her book provides a window into the pains, pleasures and politics of life on the land, and promotes new ways of thinking, no matter where you live.

Whos minding the farm? A shared responsibility for us all.

I NTRODUCTION

We call our planet earth, yet we dont think much about earth itself. As a proud dirt farmer, I reckon we should have a Minister for Soil. Not just a Minister for the Environment weve plenty of those, at federal and state levels, and they rarely mention soil. When the UN formulated its seventeen Sustainable Development Goals in 2015, soil didnt rate a mention in those either. Yet soil is at the heart of achieving many of those goals, including the elimination of poverty and hunger; and clean water, sanitation and good health.

Soil: youd think it was a dirty word.

While the UN was developing its goals, there were environmental crises all around the world, in this the Anthropocene period, a time when material wealth has finally come up against the Earths biological capacity to support it. complexities are so overwhelming that it seems were unable to make proper decisions. Do we believe that soil is as resilient as we are? While its taken a beating, its natural ability to filter contamination has provided a buffer to total annihilation. But theres a limit. Some soils are exhausted.

Humans have always farmed within particular cultures, but with many traditions in common. Agricultural knowledge was once as basic as what our mothers taught us about washing our hands and cleaning our teeth. But unlike those domestic lessons, agricultural traditions are being lost. With ever fewer people working on farms, how could it be otherwise? Despite all the new technology, all the information now available in cyberspace, weve failed to pass on the simple things required to grow our own vegetables.

Inevitably it was Australias pioneers who began the process of the great soil loss the structural depletion, the acidification, the compaction and the nutrient loss, in a country whose thin soils didnt have a lot to begin with. Habits are hard to break, and those bad habits that started the destruction linger on, but the spread of drug-addicted industrial agriculture in this epoch of agricultural imperialism cannot continue. It must not be the future.

The fifth of December is World Soil Day. human species, we need to think not in terms of preserving some unspoilt ecosystem or a patch of pure soil, but in terms of repairing the damage. Its time to face the facts and to try to change those facts.

I like to think of our farm, Elmswood, in the Hunter Valley, as an old/modern, small family operation, but its still part of a global trade system. And no matter how we strive to do things differently, in a healthier way, theres no escaping the fact that were connected to the farms next door, where our beliefs and practices may not be shared. And those farms are connected to the farms next to them, and to a world of agriculture in crisis. No farmer farms alone. We turn to each other in times of trouble, during drought or when bushfires threaten, and we often turn away from each other when it comes to views on the use of chemicals or climate change. Agricultural chemicals are manufactured synthetic products including pesticides, herbicides, highly soluble fertilisers and are the foundation of modern industrial agriculture. But manufactured synthetic fertilisers arent doing the job any more, and plants are resisting herbicides. The whole farming sector needs to do things differently. The International Federation of Agriculture Movements (IFOAM), describes organic agriculture as a production system that sustains the health of soils, ecosystems and people. It relies on ecological processes, biodiversity and cycles adapted to local conditions, rather than the use of inputs with adverse effects.

Farms can and should be places of healing, for both humans and soil. I believed that when we bought Elmswood in 1986 and

The national mythology has the heroic pioneer braving a strange new land to make a life and a living. A large part of that myth, the idea of terra nullius , allowed vast tracts to be turned into private property, which was divvied up between white men, sometimes with pseudo-legal paperwork, more often simply squatted on by the entrepreneurs of the day. Farms and districts began to specialise here beef, there wool or grain or wine or cotton, even such surreal crops as rice. Each making different demands on soil, demands that cannot always be met, particularly in the case of cotton and water-hungry rice.

What we have today, scattered across Australia, are the remnants of those nineteenth-century start-ups. Everything from small family holdings to industrial factories, where the product is beef, pork, chickens or eggs. Not far from us, city folk have bought a few hectares, but not to live on. Its land for fun. Somewhere for the kids to ride horses or roar around on quad bikes. For many newcomers, in fact, life on a farm is more about lifestyle, and its more common to have a pet horse than a vegetable garden. This was evident during the recent drought, when donated hay was fed to horses while the farmers were given food parcels.

Elmswood is somewhere in between these extremes 4000 hectares of land ranging from river flats to narrow valleys and steep hills where sometimes snow falls. Its a nineteenth-century homestead, a collection of cottages and huts and a shearing shed. But its first and foremost about the soil, about leaving the earth in a better condition than we found it, for the future. But for whose future? Our daughters? Or some unknown future owner? The question of who will be our farmers, and how they farm, is one that affects all of us.

It seems like yesterday, but it was 2009: Im at Mascot international airport while our daughter, Aurora, seventeen, checks in for her flight to the UK. Or perhaps more accurately her flight from Australia. Shes doing what more and more young people are doing, heading overseas to plan a future. In Auroras case its to check out the universities that have accepted her application, providing her HSC results are good enough. Travelling alone, she will couch-surf in London, Birmingham, Manchester, Durham and Edinburgh.