Acknowledgments

THIS BOOK PROJECT HAS TAKEN the support of many people. First, I am most appreciative of the team at the Fred Rogers Center for welcoming me at the archives and for providing a neighborly environment for me to study Fred Rogerss work. Former Neighborhood producer Hedda Sharapan was extremely generous in providing me interview time and primary source content. Her contribution deeply enriched my understanding of Fred Rogers and his project in a most authentic and sophisticated way. To her I am deeply grateful. I want to thank Emily Uhrin, the Fred Rogers Center archivist, who went above and beyond her call of duty to provide me with research assistance. Furthermore, she graciously transferred much of her vast knowledge of all things Mister Rogers to me in conversation, demonstrating her expertise on the programs creator and history. I thank Rick Fernandes, former Fred Rogers Center executive director, who offered emphatic supportand belief in my work. I am grateful, also, to Rita Catalano, former executive director at the center, to the Academy of Television Arts and Sciences, and to the Grable Foundation for the Fred Rogers Memorial Scholarship I was awarded in 2012 for this research project. This scholarship provided me with the necessary support to begin the project in the kind of thorough and in-depth fashion it called for.

My deepest thanks to my colleagues at the Johns Hopkins Carey Business School, especially Lindsay J. Thompson, Jaana Myllyluoma, Kevin Frick, Brandon Chicotsky, and Steven D. Cohen, for their enthusiastic and generous support of this book project. I am indebted to Nora Lambrecht for her deeply intelligent and invaluable assistance in editing the final version of this book manuscript.

I also wish to thank Ronald J. Zboray, director of the doctoral dissertation that gave birth to this book, and Mary Saracino Zboray for their intelligent and helpful feedback. I thank Brenton J. Malin for our many conversations on media theory and history, in which he generously shared his knowledge of the field, and for his dedicated support. I also want to thank Tyler Bickford for his insightful contributions to my thinking and for his most helpful feedback on this piece of research.

Many thanks to communication ethics scholars Amanda McKendree, John H. Prellwitz, and Craig T. Maier for their insightful commentaries that provided stimulus for the completion of this book project. Receiving the Best Paper Award in the Communication Ethics Division of the 2017 National Communication Association Convention for a paper based on the fourth chapter of this book has bolstered my confidence to continue my line of research in the subfield of communication ethics.

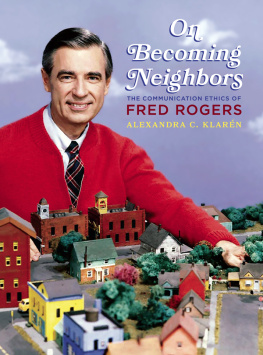

Thank you to the anonymous readers of this book, whose insightful feedback helped this project gain further focus and clarity. I am grateful, also, to Josh Shanholtzer, senior acquisitionseditor at the University of Pittsburgh Press, for his interest in On Becoming Neighbors and for his shepherding of the project to its final completion. Many thanks as well to Amy Sherman for her meticulous care in editing this book.

Finally, I thank most profusely, my parents, Peter Klarn and Sara Castro-Klarn, for inspiring me throughout my life to think critically about the world, to believe in myself, and to call upon my grandfather, Jos A. Castros sense of mote when lifes challenges present themselves. Thank you for to your unceasing love, strength, care, and support.

Introduction

IN HIS 1997 COMMENCEMENT SPEECH to the Memphis Theological Seminary, titled Invisible to the Eye, Fred Rogers, at the age of sixty-nine, reflects back on defining moments in his life. He recounts the experience of being bullied when he was an overweight and timid young boy. Afraid to go to school each day, he was, in his own words, a perfect target for ridicule. One day, after being released from school early, he decided to walk home. Soon after leaving the school grounds, he noticed that he was being followed by a group of boys who quickly gained on him while taunting him verbally. Freddy, hey, fat Freddy, they shouted, were going to get you, Freddy. Rogers recalls breaking into a sprint, hoping that he would run fast enough to make it to the house of a widowed neighbor. He remembers praying that she would be home so that he would be taken in and sheltered from the ensuing threat. She was indeed home, and Rogers found refuge.

As one might imagine, the painful feelings of shame that resulted from the social abuse and ostracism of bullying affected Rogers deeply. He recounts how, when he told the adult caretakers in his life about the bullying, the resounding message he received in response was to just let on that you dont care; then nobody will bother you. But, Rogers recalls, he did care. He resented the treatment and cried to himself whenever he was alone. I cried through my fingers as I made up songs on the piano. He sought out stories about people who were poor in spirit and derived identification and meaning from those narratives. I started to look behind the things that people said and did; and, little by little, concluded that Saint-Exupry was absolutely right: What is essential is invisible to the eye. So after a lot of sadness, I began a lifelong search for what is essential; what it is about my neighbor that doesnt meet the eye.

In this book I explore Rogerss search for the essential, that which is invisible to the eye, through a detailed and dynamic look into his groundbreaking, long-running public television program, Mister Rogers Neighborhoodhis lifes work. Integrating his advanced studies in both child development and Christian theology into the foundational rhetorics of his program, Rogers offered viewers a space of refuge, safety, and affirmation where dialogical connection, learning, and experience could take place at the parasocial level of television.and by encountering Gods compassionate presence during his own periods of suffering, encapsulates well the overarching directive and ethos of Neighborhood and speaks to the ways Rogers conceived of the program as his television ministry.

My overarching goal is to examine and analyze the vision, production, and reception of Neighborhood from the perspectives of communication, media and culture, rhetoric, and communication ethics. One cannot gain a thorough understanding of the breadth and dynamism of Rogerss communication project and the cultural phenomenon of Neighborhood through a consideration of the program alone; likewise, an inquiry solely into viewer mail lacks the critical other half of the communication puzzle that prompted its writingthe rhetorical offerings of the program. My study thus echoes the stages that Rogerss television creation went through from conception to production, reflection to refinement, utterance to reception and answerability. What follows covers an arc from imagining the program to implementing it and then moves on to an examination of how it was received through an analysis of viewer mail from the 1970s and 1980s. By analyzing Rogerss comments on the program, as well as episodes, scripts, other