CONTENTS

In 1978, with an arts degree from the Open University, a diploma in education from the University of Leeds and twenty years teaching experience in the UK and Africa, Frank Dawson went to live and work at Castle Head, the eighteenth-century home of John Wilkinson, King of the Ironmasters. He and a group of friends had acquired the property to establish there a private, short-stay residential field centre for studies by teenage and adult students. At the start Frank knew nothing of the Wilkinsons, but folk memories of their activities in the area led to documentary research into their lives and fortunes, and then to short study courses and field excursions, which he taught and directed. Annually, for twelve years, Frank gave a public lecture at Castle Head Field Centre on some aspect of the Wilkinsons lives. He retired in 1997 when the field centre became part of the Field Studies Council. Since then, he has linked together a continuous story of the Wilkinsons, using further evidence gathered from private and public archives up and down the country.

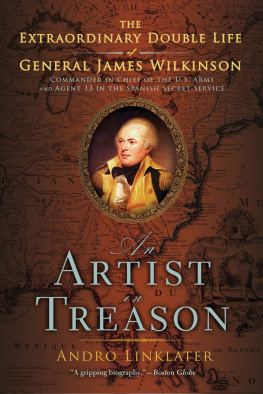

John Wilkinson was the important third man in the firm of Boulton and Watt, though he was never a properly constituted business partner. His acknowledged iron-making expertise and his engineering skills complemented James Watts inventive genius and Matthew Boultons entrepreneurial flair. He made the iron parts for the early Watt steam engines, suggested working modifications, promoted sales and organised transport. In the ten years from 1775, the three men were central figures in the dramatically developing industrial Britain.

Against this backdrop, documentary sources reveal a Wilkinson family drama on an epic scale: a father with a touch of genius, bitter quarrels between father and sons, the loss of beloved women in the uncertainties of childbirth, and a family in constant dealings with the personalities and events of the Industrial Revolution. Notably: the Darbys of Coalbrookdale; Richard and William Reynolds; Josiah Wedgwood; Joseph Priestley (who married a Wilkinson); and Samuel More of the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce, John Wilkinsons lifelong friend. These power relationships are closely examined in the building of the great Iron Bridge over the Severn; in the litigation involving Watts patent; in some early industrial espionage involving the manufacture of cannon for the British Navy; and the Wilkinsons contact with France when she was at war with England.

Everyone has heard of Boulton and Watt; few know of John Wilkinsons importance in their story. He created a vast industrial empire but had no son to inherit it, and his need of an heir led to a reputation in his old age as a womaniser and lecher. He quarrelled with some of his partners and with some of his family. Moreover he did not regard himself as bound by all the established conventions of the time: he consorted openly with a mistress, had three children by her in his seventies and left his vast empire to them, only for it to be consumed by litigation.

His contemporaries dubbed him Iron-mad Wilkinson. It is a sobriquet at once patronising and dismissive. John Wilkinson rose from humble beginnings to become a giant of his time, and he deserves better than that.

My thanks go to:

Mrs Frank Dawson (Fev) for her warm support.

Vin Callcut and Neil Clarke of Broseley Local History Society for their editorial input.

The History Press for being a very clever pleasure to work with.

Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust, Cyfarthfa Museum and Art Gallery, and the Royal Society of Arts for illustrations.

1

The father of John Wilkinson, Isaac Wilkinson, the first of this family of ironmasters, probably came to Cumberland from Washington, County Durham in the late seventeenth century, but there remains some uncertainty about his origins. Recent research by Janet Butler indicates he was born in 1695, the youngest of six children of John Wilkinson and Margaret Thompson who were married in Washington on 27 June 1678. A bishops transcript of a 1705 entry in the parish registers for Lorton, Cumberland records: Isaac, son of John Wilkinson, baptised 24 January. However, this might refer to another Wilkinson family, for if one accepts Janet Butlers dates, Isaac would have been 10 years old at this time. The further evidence, of his stated age of 80 years at the time of his death in the Bristol Register of Burials for 1784, must also be considered.

At an early stage in his adult life Isaac was a known dissenter; if he grew up with these beliefs in a family of dissenters, baptism in the established church would not have been possible. On the other hand, it may be that he developed these ideas later and that his parents, at the time of his birth, were conforming members of the Church of England.

It has been suggested, because of his subsequent close relationship with the Quaker William Rawlinson of the Backbarrow Company in south Cumberland (whose father had documented links both with the Bristol merchants and the Darbys of Coalbrookdale), that Isaac came north to Cumberland from the Midlands and developed his religious views from an earlier beginning. He certainly moved south to Wrexham in his middle life, but whether that was a return, or another beginning, remains uncertain. We do know that he died in Bristol in 1784 but, in the meantime, there is further evidence for his northern roots.

Firstly, we know Wilkinson is a northern, rather than a Midlands, name. The church registers in the Lake District of present-day Cumbria are full of Wilkinsons, and the IG (Mormon) Index for the old county of Cumberland lists literally hundreds of them. Secondly, there is documentary evidence to show that Isaac came to the Backbarrow Company, on the River Leven between the southern end of Lake Windermere and the sea, from Little Clifton in Cumberland in 1735. due east of Workington town, and about 8 miles by road north-west from Lorton. It lies in the mouth of the broad vale of the northward-flowing River Marron, a couple of miles from its confluence with the Derwent.

There is a church record, however, from the parish of Skelton, also close to Workington, for the year 1727 which records: January 20th: John, son of Isaac Wilkinson and Ann his wife, baptised. If this is our Isaac, he was married by the age of 32 (or by 22 if one accepts the alternative evidence) to someone called Ann, whose maiden name is unknown. There is further confusing evidence for that year, too. From Brigham church, a village in the area just to the west of Cockermouth, comes a record that indicates Isaac was married there on 9 September 1727 to Mary Johnston, by banns. He was 23 years old at the time. The date and the name of his wife, but not his age, agree with Janet Butlers evidence. If both records are accepted for Isaac then two things follow. First, the baptism record would mean that Isaacs dissenting ideas could not have developed fully by that time, since his child was baptised into the Church of England. Second, his wife Ann of the January record had died, possibly in childbirth, before he married Mary in the September. A possible explanation for some of the confusion begins to emerge.

Isaacs first marriage, sometime before January 1727, the date of the baptism of the John above, is to a woman called Ann about who little is so far known. She dies in childbirth and the infant John (who may or may not have survived) is baptised. It is perhaps this tragedy which turns Isaac away from the beliefs and practices of the established church. As a young widower, he meets Mary Johnston and marries her later that year. The following year their first child is born, but there is no church record of this birth or baptism because the father is now a dissenter. Such a scenario would be supported by all the evidence quoted above, with the one discrepancy of Isaacs age.

Next page