Table of Contents

For my parents

Alan and Ruth.

Your son was (and still occasionally is) quite the jackass,

but youve always been cool.

Nothing but love.

PREFACE

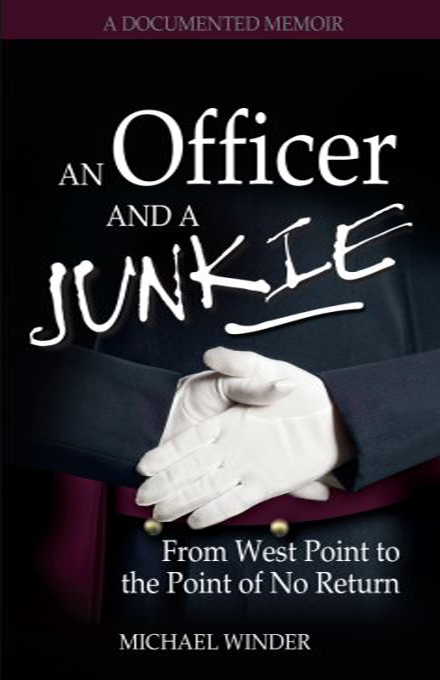

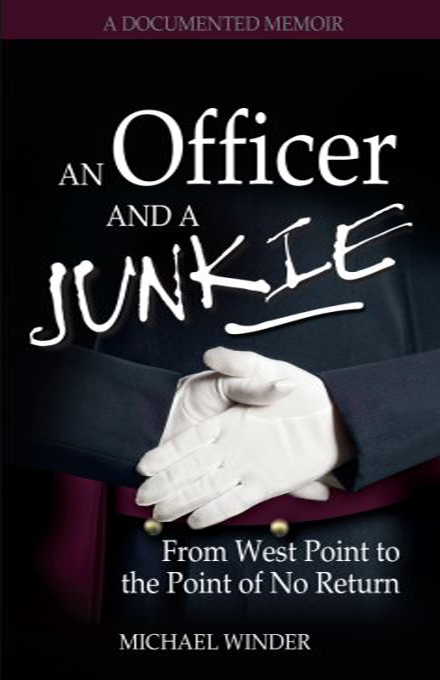

An Officer and a Junkie: From West Point to the Point of No Return is the story of my disastrous foray into drug and alcohol abuse. My tale unfolds chronologically as I tell my story month to month: first as a cadet at the United States Military Academy at West Point, then as an officer in the United States Army, and ultimately as a civilian.

My main intent is to paint a revealing picture of how ruthless and insidious the disease of addiction can be: it can strike anyone, anytime, anywhere, and such habits can be desperately hard to break.

Counterintuitively, part of the problem with addiction might be the seemingly logical push to deglamorize drug use. In a simpler, Brady Bunch world, peer pressure was the main cause of drug use in children. It might seem reasonable to think, then, that antidrug public service announcements should portray addicts as emotionally haggard and neglected misfits, lacking all responsibility, accountability, or motivation. The clear message has always been that drug and alcohol abusers are losers and failures. Although this message is difficult to argue, this addresses only the consequences of abuse. The causes cannot be simplified quite so easily, and this is obviously the next front of the war on drugs: the front end, not the back end.

My experience in drug use and addiction has shown me that addicts come from all socioeconomic and ethnic backgrounds, all ages, both genders, and all religions. Addiction does not appear to discriminate. Indeed, there is only one part of addiction that frequently seems to follow demographic lines: the drug of choice. Just as a poor background with poor prospects for future advancement can lead to substance abuse, the desire for continued success in a highly demanding environment can easily instigate and encourage addiction. In this way, and combined with an ingrained tradition of alcohol abuse, even prestigious institutions like West Point and the U.S. Army can be perfect breeding grounds for disaster.

I hold a high regard for truth in memoir and am well aware of its pertinence lately; accordingly, I have tried to keep this book focused on the facts. Trust me; it wasnt easy. Truth can be so very tedious. On the upside, Im reasonably confident that Ive written a book thats 99 percent kosher, with all events represented as candidly and accurately as possible.

That being said, I do not walk through life carrying a video camera or cassette recorder. Although I stand by all the events in this book and have not intentionally changed anything to support the progression of the story, I would like to remind the reader that memoir literally means memory. Accordingly, all the events and dialogue herein are reflected to the best of my recollection and have been verified through external resources whenever feasible.

To maintain authenticity, I have used peoples real names whenever possible. However, I have changed names for all those who might have done something that may be considered improper.

I initially began writing this book for cathartic reasons, to help with my recovery process. It was only after several months of writing that I realized I might actually have a unique and interesting story to tell. It also occurred to me that others might be able to learn from my mistakesmy story is first and foremost a cautionary tale. Finally, lets be clear on one thing: I shouldnt be alive to tell this story. If you come away from reading my book feeling inspired to try a drug, well, you are even stupider than I was. In that case, Godspeed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Special thanks to my brother, Jason, whose support of my writing has been nothing less than invaluable. I am grateful to have such good friends as Vanessa and Josh: youre important.

Thanks to Dr. Daniel Mathalon and the rest of his fine staff at the West Haven, Connecticut, Veterans Administration Hospital: youre good people.

Finally, my appreciation also goes out to Gary Heidt and Stephany Evans of FinePrint literary management, who have given me two things everyone deserves: constructive criticism and a second chance.

Part One

JOINING THE RANKS

1996-1999

R-Day

July 1, 1996

This was probably a bad idea, I think.

We pass through Thayer Gate. Everything is gray. All around us are large, drab, gray buildings. Military police usher us through the gates. They wear camouflage uniforms, with black field boots, white gloves, and 9 millimeter (mm) pistols holstered at their sides. Their rigid movements, deadpan eyes, and sharp, well-articulated voices are far, far too real.

Im in shock. What am I doing? I wonder. This is only the first of a thousand times today that I will ask myself this question.

Its Reception Day (R-Day) at West Point. R-Day is a new cadets first day of Beast Barracks, simply known as Beast, the affectionate moniker given to the six weeks of Basic Field Training undertaken by new cadets. For most cadets, military training and education begins on R-Day, when they enlist in the military, complete in-processing, take the Oath of Enlistment, review medical records, and begin practicing drill and ceremony movements that include learning to stand at attention, marching, saluting, and turning.

I had visited the Academy twice before, for my physical exams. I saw spectacular scenic views, the schools well-known distinctive buildings, cadets in uniform, and beautiful statues and monuments dedicated to important historical figures and alumni such as Generals Dwight Eisenhower, Douglas MacArthur, George Patton, and John Pershing.

On my previous visits I had not walked around the post or spoken with a single cadet about what the school was like, nor did I ever speak to any graduate. I had made a point of learning as little as possible, hoping that this might ease my trepidation and prevent me from changing my mind. I wanted to be a cadet, a part of the highly revered Long Gray Line, but I did not want to be dissuaded by the rigorous program. This was a challenge I deeply wanted to rise to, but I didnt have the confidence that I could to adhere to rigor and discipline, so I tried to avoid the knowledge of the specifics of training at all costs. Now everything looks so foreign to me. Everything looks so military. I think of Robert Heinleins Stranger in a Strange Land. This is indeed a whole new world.

I am standing in the Holleder Center, on the floor of the Academys basketball gymnasium, saying good-bye to my parents. I am determined to look calm, cool, and collected. I dont want to show how nervous I really am, especially in front of my dadthe six-foot-six, outspoken, tough-as-nails Jewish boy from the Bronx. My emotions are a weakness for me, an uncomfortable vulnerability.

So, how are you feeling? my father asks in his most relaxed voice.

Good. You know. Fine. I glance at my feet.

Nervous? he asks.

No, not really. Maybe a little. But thats probably to be expected, I say. Is my anxiety that obvious? I hope not.

Of course it is. He gestures vaguely to the hundreds of other new cadets saying good-bye to their families. Do you think any of these guys here arent nervous about today? Of course they are! Its only natural. Theyre all going through the same thing. Youre going to do fine.

Next page