Contents

Guide

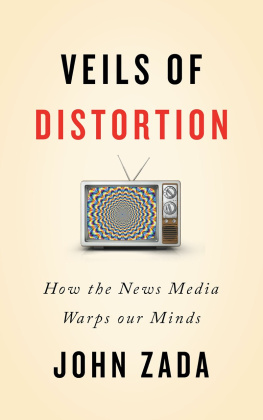

How Modern Media Destroys Our Minds

Contents

Introduction

We begin with a vast and somewhat incendiary claim: that the media amounts to one of the great contributors to anxiety, confusion and dread in the modern world; that it is responsible for stoking overwhelming degrees of hatred and distraction; that its business models forces it to exaggerate discord; that our advanced technologies of communication have served to supercharge our tribal impulses, and that our capacity to regain a measure of sanity and serenity now depends on learning to approach the content of much of the media with extreme caution and circumspection.

None of this isof courseanything were encouraged to think about by the media itself. While relentlessly drawing our attention to the misdemeanours of others, the one problematic dimension the media does not linger on is its own. It typically normalises its role in our lives. It tries to make it seem reasonable that we might check on its updates ten or thirty times a day, stepping out of a childrens birthday party or interrupting a walk with our grandmother to inform ourselves of new topics of outrage and terror. It romanticises the moral character of its corporations. It brazenly tells us that it is a supreme source of insight and knowledgeand aligns itself with the progressive forces of science, democracy and justice.

Though susceptibility to a lot of the medias output may cause us difficulties, it is far from delusional. Rather than heralding the breakdown of our minds, an intense response to what we have heard or read on our screens may be the surest evidence yet that we are highly attuned to reality and authentically worried about our species. Indeed, we might wonder what might be faulty or closed-off in someone who wasnt pushed into fear and despair by what they took inand what might have gone wrong if they managed to remain indifferent in the face of all the provocations and frenzy on their newsfeeds. What would enable them to read comments below an article or follow the digital hounding of strangersand to continue with their day unmolested? To be traumatised by mass and social media isnt necessarily a proof of madness; it may be the surest sign yet of having remained (against all odds) a balanced and thoughtful creature.

The media often tries to convince us that it has no capacity whatsoever to harm usand that it would only be its absence that could ever do so. Our response to this line indicates a deep confusion as to the power of words and images, which we seem simultaneously to think can affect us a lotand in the end not so much at all. On the one hand, we are boundlessly respectful as to what a few finely rendered square centimetres of canvas can do for our souls. Works of art are accorded a centrally prestigious place in our societies: governments spend millions to house and light them correctly, schoolchildren are bussed in from distant corners to sit respectfully in front of them. A group of 8-year-olds will be told to arrange themselves in a semicircle in (for example) the august halls of the National Gallery of Denmark and to look up at a painting by Vilhelm Hammershi of a woman alone in a white room on a sunny dayand will be informed (though not in precisely these words) that they are in the presence of transcendent greatness.

Vilhelm Hammershi, A Room in the Artists Home in Strandgade, Copenhagen, with the Artists Wife, 1901.

The claim isnt too strong. Hammershi is indeed one of the greatest painters. We should ideally spend a good few moments looking at one of his works every day. But we cannot logically have it both ways: either images matter greatly, or they dont very much. And if we assume that they do, then we have to wonder what it must be doing to our spirits to commune on an hourly basis with pictures of mobs, riots, murderers, scandals and disasters. What must be happening to our minds in the face of so much that we are exposed to? We cant make an exception for the so-called good images and dismiss the role of the troubling ones. If pictures can save and enhance us, they must alsoby the same measurebe able to depress and disorient us. Some of our perturbations of mind must come down to what we have been too innocently looking at for far too long.

Do images count? Or not at all?

It comes down to a question of how sensitive we might be. It took a long time for us to realise how much children register and feel. For most of history, it was assumed that you could rough up small people without too much consequence; you could shout at them, humiliate them, ignore them and beat them, and their lives would carry on more or less without harm. It took many centuries, millennia indeed, until the true fragility of their spirits was noted. In the middle of the 18th century, in the paintings of Thomas Gainsborough, we catch the first glimpses of a new awareness of the impressionability of children. In a study he made of his daughters from 1756, Margaretthen aged 5reaches out to touch a white butterfly while her sister Mary (a year older) both restrains her and expresses her own curiosity. Were in no doubt that something very important has just happened in the brief lives of these children, and at the same time, we know that this is no more than the fluttering of the wings of a cabbage white. Not coincidentally, just before the painting was made, Britain and France began fighting what became known as the Seven Years War (17561763), a global conflict that unfolded across five continents in what Winston Churchill termed the true first world war. But Gainsborough was deliberately turning his gaze elsewhere, as if to make the novel suggestion that the difficulties and joys in the lives of children could be as significant as manoeuvrings in high politics or the posturings of statesmen.

Thomas Gainsborough, The Painters Daughters Chasing a Butterfly, c. 1756.

We understand now how shy children can be, how distressed they may get by the boisterous laughter of a stranger or a jostling in their environment, how much they need to be left in peace to develop at their own pace and how they should be protected from intrusions that they are too defenceless to handle. But their vulnerability is not theirs alone. In substantial part, we retain it throughout adulthoodexcept with the added problem that we believe ourselves to be immune to the influence of what we insist on calling small things. Feelings of helplessness, anger, frustration, sadness, guilt and shame get lodged inside us without us being able to notice them, let alone gain relief by communicating them. We dont realise how upset we have been made by a stray remark or a rumour. We suffer with all the intensity of small children while assuming ourselves to be hardy and well-armoured soldiers.

One of the most surprising ideas found in the canonical text of ancient Greek philosophy, The Republic, written by Plato around 375 BCE, is the claim that in the ideal state, art should be banned. Plato proposes that playwrights, musicians, sculptors and poets should collectively be shown the door andif necessaryforcefully instructed to stop working. What might have led this otherwise enlightened and civilised philosopher to make such a proposal, which we associate with draconian regimes and dictators? Why would anyone have a problem with art circulating without impediment? It might have looked as if this idea sprang from a lack of respect for the arts, from a tone-deaf martial philistinism. But far from it. Plato wanted to ban art not because he thought it was an unimpressive medium, but because he was in awe at its capacity to reconfigure our minds. More than liberal thinkers who blithely incline to leave all wordsmiths and picture makers to themselves out of a background feeling that more or less anything can be witnessed without much impact, Plato understood how significant art could beand he wasnt merely thinking of pornographic or explicit works; his warnings stretched to encompass the sculptures of Myron and Leochares and the plays of Aeschylus and Euripides.