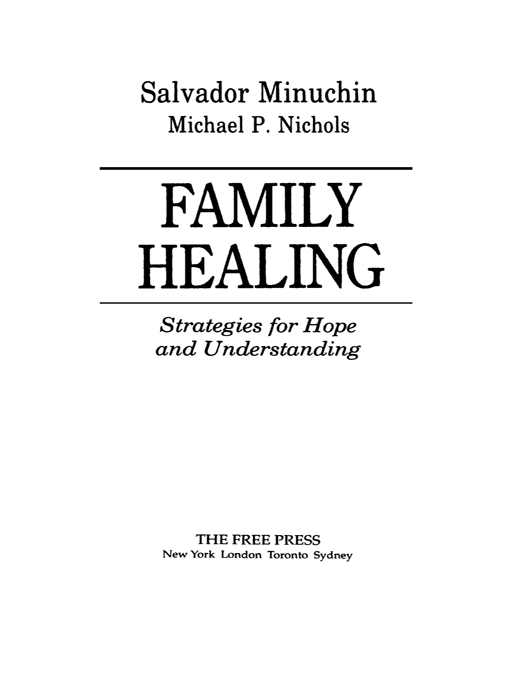

THE FREE PRESS

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 1993 by Salvador Minuchin and Michael P. Nichols

All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form.

First Free Press Edition 1998

Published by arrangement with The Free Press, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

T HE F REE P RESS and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster Inc.

Manufactured in the United States of America

5 7 9 10 8 6 4

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN-10: 0-684-85573-9

ISBN-13: 978-0-684-85573-8

eISBN: 978-1-439-10789-8

Contents

Contents

Preface

Preface

After thirty years as a family therapist, I proclaimed myself an elder. After all, I was there when family therapy began. I was one of the ones who helped it grow, and I have seen it move, for better or worse, from being a radical new departure, a novel way of looking at people and helping them, to its present secure position within the mental health establishment.

In the best tradition of storytelling, the elder, seated on a low bench, regales his audience with the exciting adventures of his youth. So I wrote four autobiographical chapters. But when I began to look at cases that could represent a universe of families and describe the way I work, I felt overwhelmed by proximity. I realized that one of the barriers to an honest account of therapy would be the tendency to read my own theories into my client families, recreating them in my own image. The collaboration with Mike Nichols began at this point. Together we reviewed dozens of cases to select ones that would illustrate various stages of family development and the issues that crop up to bedevil all families. Although we included some exceptional and unusual families, most of the stories in this book are about ordinary human beings learning lifes painful lessons. Mike took on the thankless task of transcribing the tapes of the sessions and brought fresh eyes to encounters that had become so much part of me that I was in danger of imposing my bias on what actually happened. As you will see, I have tried to help the reader understand some of the critical issues that families wrestle with and some of what was going on in my own mind as I tried to help them solve the problems that brought them to therapy.

After Mike sent me the transcripts, I went over them to reduce them to manageable size and to add my thoughts about the meaning of the therapeutic encounter. We met on numerous weekends, going over the material together, pruning the superfluous content, and rechecking the tapes to ensure complete accuracy. It was a rich and satisfying collaboration.

Because I wanted to let the family members tell their own stories, we limited our selection to cases for which I had tapes. For that reason we could not include some long-term treatment cases. We also excluded the whole body of my work with poor and welfare families. I felt that the characteristics of this work would require a description of institutions and larger systems than could be encompassed in the format of this book. Naturally we changed the names and identifying characteristics of the families, but otherwise the stories you read are told exactly the way they happened.

I want to thank my wife, Pat, who has been an integral part of my life for more than forty years and now shares more than half of my memories. She read and reacted to the stories, but her participation in the autobiographical chapters was even more essential: She brought flavor and accuracy to my description of the events we lived together. I thank her for the past and for the present.

As with all my previous books, I want to thank Fran Hitchcock, who has become indispensable in my writing. She is my grammarian, editor, sounding board, critic, and friend. Mike and I would also like to thank Joyce Seltzer of The Free Press for expert guidance and encouragement.

PART ONE

THE MAKING OF A FAMILY THERAPIST

THE MAKING OF A FAMILY THERAPIST

1

Family Roots

Family Roots

FEBRUARY, 1992

I am in a state psychiatric hospital to do a consultation with Tony, age ten, and his family. Before I see the family, the staff tells me about Tony. I listen attentively. When he was eight his mother took him to a prestigious university hospital, where he remained for ten months. His diagnosis was attention deficit disorder, a variation on the previous label, minimal brain dysfunction, that replaced his first diagnosis, hyperactivityall of them meaning pretty much that the child has poor impulse control and a short attention span. In the university psychiatric ward, doctors tried to find the appropriate dose of medication that would make him fit to return home. After trying a variety of doses and medications, they decided to refer him to a state psychiatric hospital. Tony has been here for a year, so he has spent 20 percent of his short life in psychiatric wards.

At the state hospital Tony has individual, group, recreational, and sundry other therapies. He attends a highly structured school and lives in a cottage with other children in a token-economy milieu, meaning that they earn stars for good behavior that can be exchanged for special treats later on. Focusing not on Tony but on his neurological system, the psychiatrist rattles off a long series of pharmacological trials. He says that at the university hospital, Tony was given Ritalin and Mellaril, with the focus on aggression and the attention problems, while here the issues of separation anxiety are the focus of the medication efforts. To that effect, he says, Tony was tried on and then off Clonidine, showing clear differences on and off medication. Toward the end of December he was begun on copharmacy of Lithium with the antidepressant: We are a long way, I would say, from expecting self-control in a home situation that can still destabilize, which destabilizes Tony when it does.

The precision with which the ten people talking with me cover up the narrowness of their point of view impresses me. When I ask about Tonys future, the answer is a vague hope that he will spend less than another year in the hospital, and then something like a lifetime in what the psychiatrist calls parallel institutions. I assume that these are day hospitals or less restrictive settings. And Tony is only ten years old!

Next page