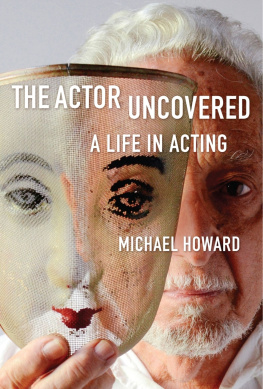

Copyright 2016 by Michael Howard

All rights reserved. Copyright under Berne Copyright Convention, Universal Copyright Convention, and Pan American Copyright Convention. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Allworth Press, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Allworth Press books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Allworth Press, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

20 19 18 17 16 5 4 3 2 1

Published by Allworth Press, an imprint of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.

307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Allworth Press is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

www.allworth.com

Front cover photo credit Whitney Bauck

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Print ISBN: 978-1-62153-549-2

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-62153-558-4

Printed in the United States of America

This book is dedicated, as is the best of my life, to my partner, my wifethe extraordinary Bettyand to my sons, Matthew and Christopher .

We take our work seriously, but not ourselves.

Michael Howard

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction

By Michael Kahn

There is no one who has had a more lasting influence on my journey as a theater artist than the wise and generous Michael Howard, the author of this wise and generous book.

I first met MichaelMr. Howard as he was then to meat the beginning of my third year at the High School of Performing Arts when he became the principal acting teacher of our class.

From a very early age, I knew I wanted to be a part of the theaternot as an actor but, surprisingly and mysteriously, as a director. I was taken to many plays by my mother and various aunts and appeared in, wrote, and directed plays in grammar school and for my little troupe of players in one of my friends backyards. My parents agreed to enroll me in acting class, which met on Saturdays near Rockefeller Center. A pretty, redheaded instructor handed us monologues, which we learned and performed while she sat with the script and marked with up and down arrows as to where the intonations should be.

When I heard about the High School of Performing Arts, I begged my parents to let me try for it, even though it meant traveling to midtown New York from our Brooklyn Heights apartment. The audition morning arrived; armed with two monologues, I entered a room in which a panel of faculty members sat, and with a pencil taking the place of a cigarette in an elegant holder, I channeledor rather imitatedGeorge Sanders in the opening monologue of All About Eve , to the effect that: Margo Channing became a star at the age of eight appearing as a fairy in A Midsummers Night Dream . Shes been an actor ever since. (I myself was twelve.)

When the audition (which included an improvisation) was over, one of the judges said they couldnt tell me anything that day but added that I must not under any circumstances go back to that Saturday acting class ever again.

I was accepted at Performing Arts and the first two years were alternately exciting, bewildering, and upsetting. My mother died of cancer, my father remarried soon thereafter, I now felt a stranger at home, and the faculty at critiques made it clear to me that I would never be an actor. I lived in fear of the dreaded letter that was sent to students every six months informing them whether they could continue in the program or must transfer to another school.

I had always done the work, including improv, sense memory, writing down beats, and my intentions (even before I had done anything with my scene partner!), but apparently to no avail. Still, the chairman of the drama program saw something in me that made her believe there would be a place somewhere for me in the profession, and so I was allowed to remain.

Michael Howard began working with us in the third year. We began by not rehearsing the text, as I had been doing, but rather improvising extensively around it: We acted out the given circumstances rather than intellectualizing them (oh, how that word kept coming up for me!) and did various exercises in which we covered up the script, said our lines with an intention, and then listened to our partner without sure knowledge of what was to come next, allowing our response to exist before we read the next line. I think this was my first inkling of what subtext might mean and what being in the moment truly was. Michael insisted on a full relaxation exercise in advance of starting work on the scene and then a preparation of the circumstances before the scene began . Once, my partner and I, doing a scene in which we were supposed to be late for a ferry ride, left the school building (which was then on 46th Street), ran down to Broadway and back, entered the school (an accomplice was holding the door open), and arrived onstage, panting realistically, to make our boat ride. Luckily we were young and so still had enough breath to say our lines.

What was most crucial for me was to feel free to bring whatever was going on withinmy internal stateinto the scene. This work, which finally took me out of my head (which had been constricting me and making me direct and judge myself), began to gel under Michaels encouragement, and one miraculous afternoon, when my partner and I had finished a scene (of all things Pygmalion!), the feeling that it had all happened in the presentall spontaneous though rehearsedfilled my body and I knew what living on the stage could be. Subsequently, Michael surprised me by casting me in the Fourth Year Project, and upon graduation I received the Best Actor awardand the first wristwatch I ever owned.

I continued to study with Michael in his private evening classes when I was at Columbia University. One evening he took me aside and told me he was going to have to leave the class for a while in order to direct a play on Broadway and he wanted me to fill in for him. I was flattered but hesitantmany of the students were older than I was, but Michaels faith in me allowed me to say yes and so began a teaching career that has run side by side with my directing. Michael had taught me to act, which as a director has helped me to understand an actors process, and now he was encouraging me to teach, and those skills have sustained my career throughout my artistic life.

Later, because I had worked for Michael in summer stock as an apprentice and as an assistant, it was one of the great joys in my life to offer Michael the lead in a production of two Ionesco plays that I would do off-Broadway in the spring of 1964, Victims of Duty and The New Tenant . Throughout the rehearsal process he was the actor and I was the director, and it seemed to have completed my process of becoming an adult.

I need to say one more personal thing. Michael was not only a mentor professionally; he, and his wife Betty, helped me through some difficult personal times. I ran away from home (it was only some five blocks from our apartment to the Howards apartment in Brooklyn Heights) at the absurdly advanced age of eighteen. Michael and Betty allowed me into their home and then into their family. Even though I went back to my home after a few hours, I now knew that I had another family when I needed it.