PENGUIN PRESS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

penguinrandomhouse.com

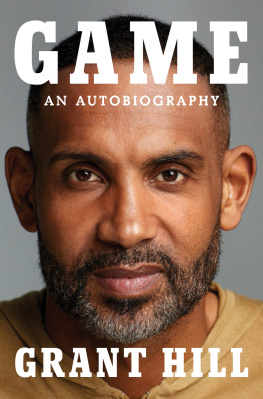

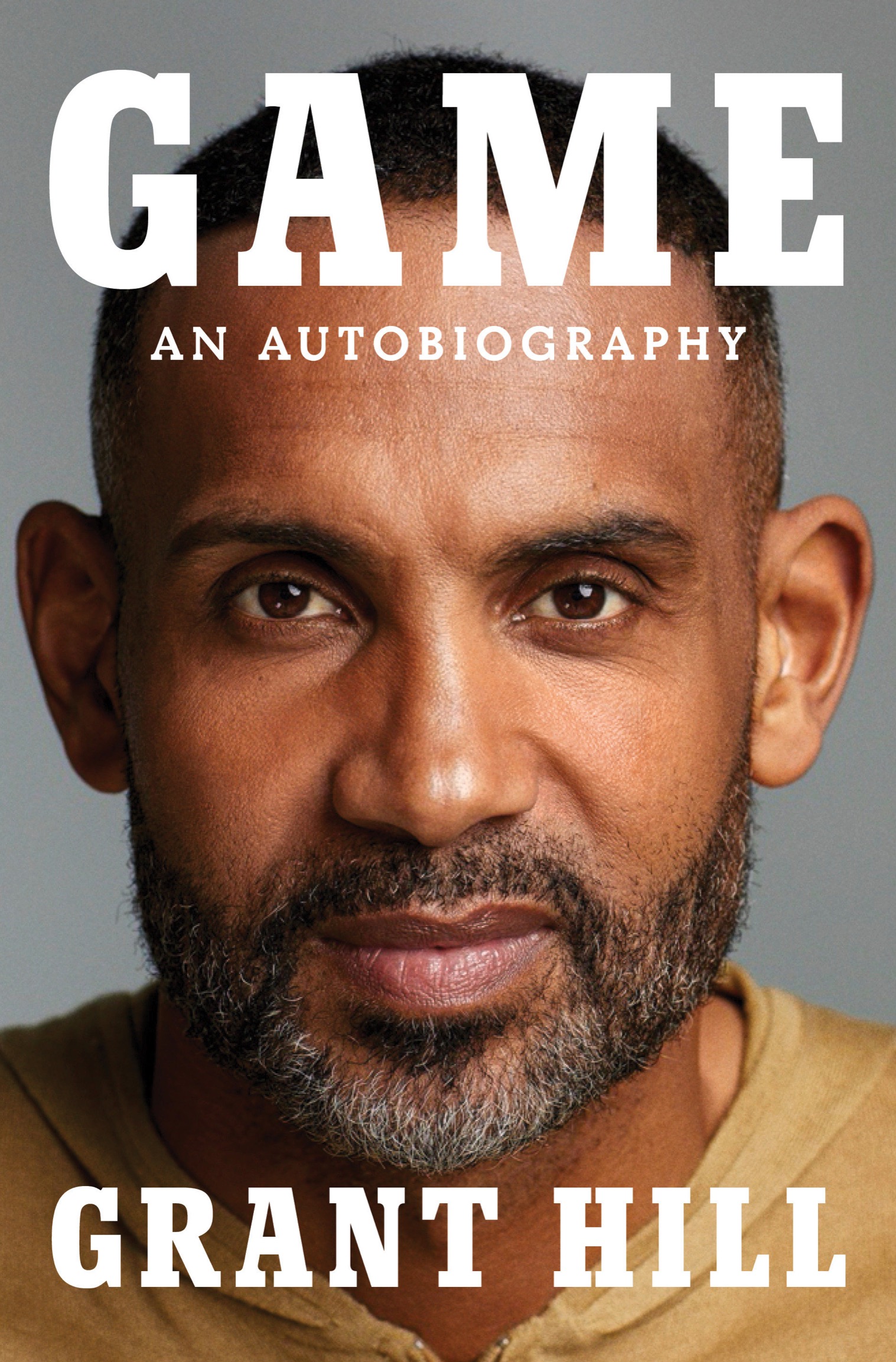

Copyright 2022 by Grant Hill

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

constitutes an extension of this copyright page.

library of congress cataloging-in-publication data

Names: Hill, Grant, 1972 author.

Title: Game : a memoir / Grant Hill.

Description: New York : Penguin Press, [2022] | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021061033 (print) | LCCN 2021061034 (ebook) | ISBN 9780593297407 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780593297414 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Hill, Grant, 1972 | Basketball playersUnited StatesBiography. | African American basketball playersUnited StatesBiography. | Basketball team ownersUnited StatesBiography. | Atlanta Hawks (Basketball team) | Hill, Grant, 1972Art collections.

Classification: LCC GV884.H45 A3 2022 (print) | LCC GV884.H45 (ebook) | DDC 796.323092 [B]dc23/eng/20220126

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021061033

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021061034

Cover design: Darren Haggar

Cover photograph: Celeste Sloman

Book design by Daniel Lagin, adapted for ebook by Cora Wigen

pid_prh_6.0_140138093_c0_r0

For Mom, forever my hero.

Contents

1

WE were there for basketball and basketball only. Howard Garfinkels Five-Star Basketball Camp was a hoops mecca throughout my teenage years, a rite of passage for the nations top prep basketball players to measure ourselves against one another and be seen by college recruiters. The camps stretched for weeks each summer through different sessions at Honesdale, the more coveted camp hosted in the Poconos, and Robert Morris University, near Pittsburgh. In middle school, I had flipped through a Sports Illustrated and first learned about Five-Star, this mystical camp run by a character named Garf. I attended the first time the summer after my freshman year of high school. Michael Jordan, Patrick Ewing, and Chris Mullin attended the camp before me. Kevin Durant, LeBron James, and Chris Paul made the trip after me. Coaches also made names for themselves as camp instructors. Bob Knight, Jim Valvano, and Rick Pitino passed through as counselors. John Calipari, then a fresh-faced assistant at Pitt, was among my coaches at that first camp.

I was headed into my senior year of high school in the summer of 1989 and had become accustomed to the camps rhythms when I arrived again in Honesdale. I had attended one of the camps earlier that summer and impressed enough to earn the MVP of the camp and All-Star Game. Garf was a warden, counselor, and coach all rolled into one, a New Yorker who started the camp far outside the city lights in 1966. He woke us by blasting Frank Sinatra each morning and spent his days motoring from station to station in a golf cart. A cigarette stayed glued to his lips as he talked in bits and spurts.

Everything about the camp was old-school, steeped in tradition. Garf insisted he was running a camp and not a meat market. He bypassed luxuries. We ate breakfast before the drills and rotated every twenty minutes while learning the fine points of various fundamentals. Most of the courts were outside where gnats and flies filled the thick air. A comforting cacophony constantly echoed from the courts lined by birch trees: thudding basketballs, squeaking shoes, shrieking whistles. Lunch usually featured a talk from a big-name coach. We sat in a ring around the court and listened, offering a standing ovation when it ended at Garfs instruction. In order for the afternoon sessions to begin, Garf had to hit his daily shot. We cheered him on, hoping that his attempt found the basket quickly so that we could get on with more instruction and games.

Garf personally identified the best players throughout the country and invited them to attend the camps on scholarships. In return, we served meals and bused tables for the other campers. I viewed the duties as a mark of distinction, proud to earn whatever I received. My parents, Calvin and Janet, had inspired me to work hard and dream big.

You cant teach hungry, my dad always reminded me. Either you are or you arent.

Players attended to make a name for themselves or enhance their reputation. New York kids populated every camp, and this years was no different. Those guys swore they invented the sport, but the truth was most of them could ball. I had met Brian Reese at the camp the previous summer and was eager to catch up with him that year. He played forward for a nationally ranked high school in New York and was teammates with a couple other campers, Malik Sealy and Adrian Autry. Brian hailed from the South Bronx, home to one of my favorite rappers, KRS-One.

We were loitering on the outdoor courts, waiting for games to start, when a few campers started a conversation about Lloyd Daniels. Daniels was a New York legend a few years older than us who had bounced around a bit, more of a myth to me than a real player. But some of the New York guys had seen him play and painted him as a much taller version of Kenny Anderson. I was busy imagining a player of that much size oozing that much versatility when Adrian punctured my daydream.

Hey, man, why are you here?

The question caught me off guard.

What do you mean?

Youre rich. You live in a mansion. You got money, right? We need this to eat.

Adrian and I were friends, both then and later. He advanced to play at Syracuse and overseas before becoming one of Jim Boeheims assistants at Syracuse. He hadnt, I dont believe, asked me out of malice, and I doubt hed even recall this exchange today. But I figured he had somehow learned my backstory, that my dad had attended Yale and played in the NFL, that my mom was a successful businesswoman.

Adrians question was one of the first times an internal conflict had been projected outward. I grew up aware of my parents accomplishments. Sometimes, they intimidated. Often, they inspired. We might not have lived as grandly as Adrian or others envisioned, but we were comfortable.

At the same time, I spent most of my childhood wanting to blend into the background. Every article written described me as the son of an exNFL player. Im not necessarily proud of this now, but I used to hate that characterization. I wanted to prove I could stand on my own. Me busing tables showed that I was earning my way at camp. Now it seemed like Adrian was trying to take it away.

Was he implying that I was there only because of my parents? That I needed to travel a specific journey and come from a certain background to be ambitious? Or that I simply was not a good enough player to share the court with him?

I was on the edge of leaving adolescence for adulthood. By that point, basketball had already come to mean much more to me than just a sport. I had spent years advancing to different baskets in my hometown of Reston, Virginia, like they were grades in school at various recreation centers, park playgrounds, and gyms. The local legends clocked in at Twin Branches Court. The court was a blacktop where one rim hung lower than the other, the result of the iron bearing a few too many gravity-defying dunks. The park was a siren call for ballers from all over the Washington metropolitan area, guys a couple years out of school with magic still in their game and ones who went on to make a name for themselves through basketball, like Dennis Scott, who starred for the Orlando Magic, and Billy King, who went on to play at Duke.