Copyright 2021 by Christine M. Su

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise without written permission from the publisher. It is illegal to copy this book, post it to a website, or distribute it by any other means without permission.

References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. The author is not responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since this manuscript was prepared.

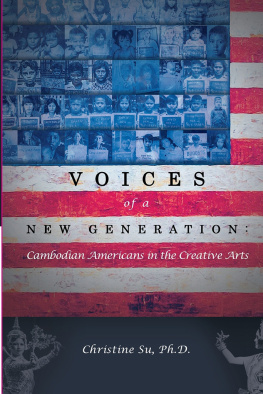

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Voices of a New Generation: Cambodian Americans in the Creative Arts/ written by Christine M. Su

Includes endnotes and works cited/suggested readings for further research.

ISBN 978-0-578-95537-7 (paper)

ISBN978-0-578-3350-2-5 (ebook)

First edition

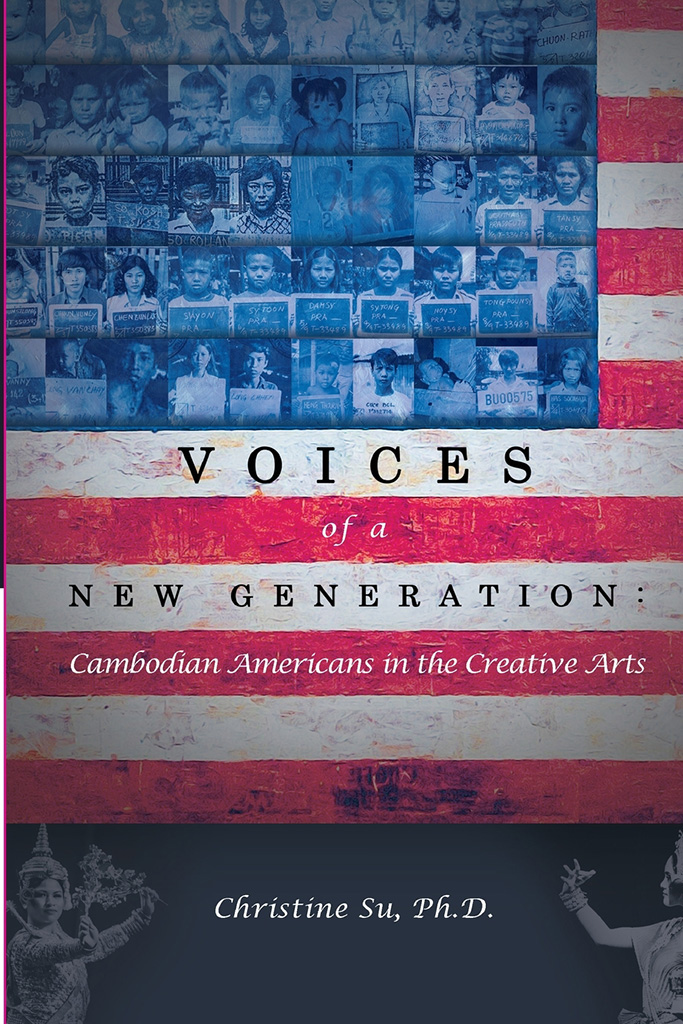

Cover art by Caylee So and Sothearos Kiep

Acknowledgements

This book would not have been possible without the kindness and generosity of so many people. I would need many, many pages to list names individually. Please know that if you have participated in this project in any way, at any point in time, I am truly grateful for your support and assistance.

Thank you to the 15 artists who shared their stories with me. Each of you holds a special place in my heart. You will touch many who see themselves in your stories--your dreams and realities, successes and disappointments--and inspire them to explore their own creativity and unleash their artistic imaginations.

Thank you to all who allowed me to use the photos that appear in the flag on the front of this book. These photos represent the beginning of many long, arduous journeys and stories of resilience, and I am honored to have them grace the cover.

Thank you to all who granted me permission to use their photos and images within the book. Oftentimes a picture speaks a thousand words, and those included in the book will help to make the stories come alive for readers.

Thank you to all who assisted me in translating words from English to Khmer and Khmer to English, and those who took the time to explain Cambodian cultural beliefs and concepts to me (often more than once).

Thank you to those who opened your homes and hearts, and for the endless cups of coffee, plates of rice, and bowls of noodles you shared with me over the years as we got to know each other.

This is the book I wish I had to read when I was growing up. Thank you for the opportunity to write it.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

LIST OF FIGURES

Kingdom of Cambodia map indicating areas mentioned by the artists in this book. 2021. All rights reserved. This image may not be used or duplicated without express permission in writing from the author.

Introduction

M y father was born in the province of Kampot, to the southwest of Phnom Penh, in a place called Tani Tuk Meas. While I know very little about his childhood, I like to imagine that daily life was much like what we see in idyllic paintings: coconut palm trees swaying in the warm summer winds, green rice fields, people making offerings at the local Buddhist temple. I like to imagine my father running along the road on his way to elementary school, wearing the typical uniform of a white shirt and blue shorts or trousers. Sadly, much of my connection with my father comes through my imagination.

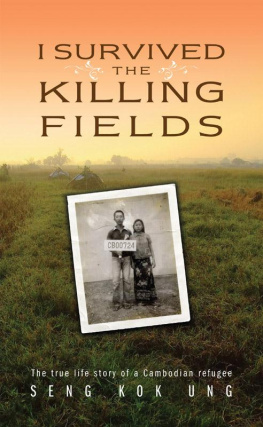

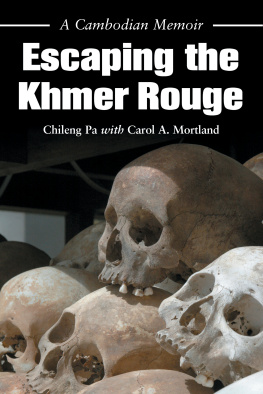

On April 17, 1975, communist guerillas known as the Khmer Rouge marched into Phnom Penh and other provincial cities, declaring victory. At first, people cheered, thinking that the bombing and war they had endured for more than a decade had finally come to an end. Instead, that day marked the beginning of nearly four years of terror. The Khmer Rouge implemented a radical Maoist and Marxist-Leninist policy with the goal of transforming Cambodia into a classless society, abolishing money and private property, traditional education, religion, and cultural practices. People were forced into the countryside to undertake arduous agricultural work from morning to evening, with little food to sustain them. Schools, pagodas, mosques, stores, and government buildings were turned into stables, granaries, torture centers, and prisons.

During the Khmer Rouge regime, more than 2 million people died of starvation, disease, overwork, torture, and execution in what became known as the killing fields. Among those were my fathers parents, grandparents, siblings, cousins, friends. Cambodia was not spoken of in our house, and as far as I knew, it was a bad place--or at least, a place I believed had stolen my fathers happiness.

It wasnt until I traveled to Cambodia for the first time that I actually began to see the beauty and brilliance in Khmer culture. I remember one day very distinctly. I had taken a taxi with some friends from the capital city of Phnom Penh to Siem Reap, where the Angkor temples are located. I of course wanted to visit the famous Angkor Wat first, but it was early afternoon when we arrived, and our taxi driver insisted it would be best to wait either until evening to see the sunset or until the next morning to see the sunrise over Angkor Wat, so instead we went to visit the Bayon, part of Angkor Thom.

Built in the 12th century by King Jayavarman VII, the Bayon encompasses hundreds of huge faces carved into stone, facing north, south, east, and west. I had gone expecting to see magnificent monuments, but not faces in the stone, faces that seemed serene, at peace. The tranquility reflected in the gentle smiles and partially closed eyes of each face stood in stark contrast to nearly all of my beliefs and perceptions about Cambodia as a grim place of war, destruction, and trauma. I looked up at them and literally fell to my knees, overwhelmed with emotion.

For the rest of the afternoon I walked among the many faces, and felt that they were watching me, comforting me. While silent, they spoke to me.

This was a pivotal moment, because I realized just how much I had been focusing on Cambodia and my Cambodian identity in a negative way. Without discounting the trauma and suffering endured during the Khmer Rouge regime (and we will never, ever forget), I realized that period is but a very short fragment within the timeline of Cambodian history. The Khmer Empire once encompassed most of what is now Thailand and Vietnam. The Khmer built complex cities and spectacular temples without modern tools or equipment, reflecting Buddhist and Hindu cosmology on earth. They expressed their love of music, dance, martial arts, cooking, adornment, and other creative endeavors on the temple walls themselves, through intricate carvings that tell tales of both everyday life and ancient mythos.

The Power of Art to Connect, to Heal

Under the Khmer Rouge regime, approximately 90 percent of Cambodias artisans were killed. The regime wanted to erase all vestiges of outside influence or elite, oppressor" culture, and targeted artists--painters, singers, martial artists, and dancers--for execution.

Yet just as the Khmer Rouge sought to eliminate traditional arts, post-war Cambodians seek to rebuild them. In so doing, they strive to repair and heal their shattered spirits.