PENGUIN PRESS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

penguinrandomhouse.com

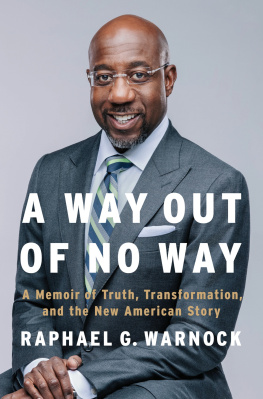

Copyright 2022 by Raphael G. Warnock

Penguin Random House supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for every reader.

Insert Image Credits: , courtesy of the Warnock family.

library of congress cataloging-in-publication data

Names: Warnock, Raphael G., author.

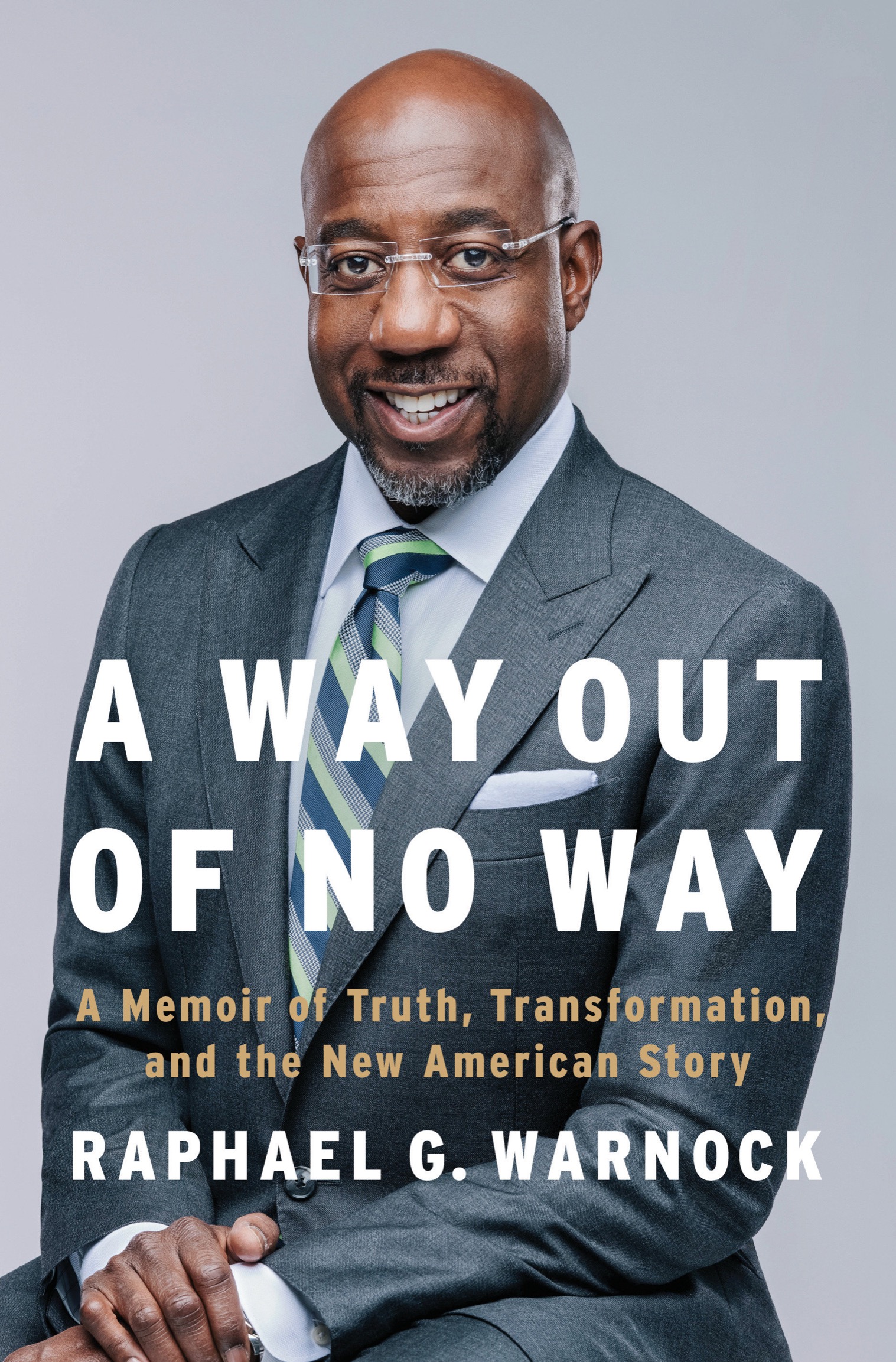

Title: A way out of no way : a memoir of truth, transformation, and the new American story / Raphael G. Warnock.

Description: New York : Penguin Press, [2022] | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2022001968 (print) | LCCN 2022001969 (ebook) | ISBN 9780593491546 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780593491553 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Warnock, Raphael G. | United States. Congress. SenateBiography. | African American legislatorsUnited StatesBiography. | LegislatorsUnited StatesBiography. | LegislatorsGeorgiaBiography. | African American BaptistsClergyBiography. | African American political activistsGeorgiaBiography.

Classification: LCC E901.1 .W367 2022 (print) | LCC E901.1 (ebook) | DDC 328.73/092 [B]dc23/eng/20220201

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022001968

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022001969

Cover design: Stephanie Ross

Cover photograph: Nina Kossoff

Designed by Cassandra Garruzzo Mueller, adapted for ebook by Cora Wigen

pid_prh_6.0_140193378_c0_r0

For Chlo Ndieme and Caleb Babacar,

With all my love and prayers for your future, and with profound gratitude for the best title ever!

Dad

Do not get lost in a sea of despair. Do not become bitter or hostile. Be hopeful, be optimistic. Never, ever be afraid to make some noise and get in good trouble, necessary trouble. We will find a way to make a way out of no way.

Congressman John Lewis

Contents

CHAPTER 1

Boys Like Us

I could tell by the sound of my mothers voice. Something was wrong.

Ray, she said, taking a deep sigh before finishing her voice-mail message that day in September 1997. I need to talk to you about something.

My mother, Verlene, then fifty-nine years old, is a proud Georgian, having spent nearly all her days in the 110 miles between the towns of Waycross, where she was born, and Savannah, where she eventually landed and raised her own family. Mom is a preacher with a God-given sense of spiritual discernment, or what some might call a sixth sense, and she could read people and situations better than anyone Ive ever known. So, when she said she needed to talk, I was always inclined to listen carefully.

When she called me that day, I was living in New York City, pursuing a doctoral degree at Union Theological Seminary, and working as an assistant pastor at Harlems iconic Abyssinian Baptist Church. As the eleventh of twelve siblings in our big family, I was the first to graduate from college, and my parents and siblings were protective of me. They tried hard not to distract me with bad news from home, which usually meant I was the last to know if something was wrong.

So, Mom, whats going on? I asked when I reached her later that day at home in Savannah.

Keith got arrested, she said finally, referring to the brother one step above me in birth order, though we are five years apart. She sounded sad and exhausted. I was stunned. Hurt. Confused. My big brother, the proud police officer?

Arrested? I said. For what?

There was a long pause.

Drugs, she replied.

He was charged with aiding and abetting the distribution of cocaine by providing security for drug dealers. He had been caught in an FBI sting that implicated eleven officersten current and former officers of the Savannah Police Department, and one from Chatham County.

This was incomprehensible. There must have been some kind of mistake. Not Keith, my stocky, clean-cut older brother, the high school football player who was so in love with the Dallas Cowboys that his friends nicknamed him Dorsett, after the teams celebrity running back of the 1980s. My mind flashed back to those joyful, carefree days.

Keith was the athlete of the family. He ran track and played football at Johnson High School, which first opened in 1959 on the east side of town as a laboratory school for Savannah State College (now Savannah State University), a historically Black college. The high school was named in honor of Solomon Sol C. Johnson, a prominent businessman who in 1889 became the second editor and ultimately the owner of The Savannah Tribune, one of the countrys oldest Black-owned newspapers. In our day, the school was better known for the uniqueness of its mascot, the Atom Smashers, than for the prowess of its football team. Despite Keiths famous nickname and his pretty good skills on the field as a running back, Johnson High went almost two years straight during his time there without winning even a single game. That didnt stop the fans from showing up each week, though, hoping for a miracle.

I played in the Myers Middle School band at the time. Id switched from the trumpet to the baritone horn to fill a need in the brass section of our band. One special Friday night we got to perform during halftime with the Johnson High School band on the football field at Savannah State. The Atom Smashers were ahead, and I will never forget the thrill of counting down the last seconds of that game. The miracle we all had been anticipating finally happened. The team broke its long losing streak, and the crowd went wild, as if our boys had just won the state championship. Students rushed from the stands onto the field, and I joined the flow, with my eyes darting around, searching for my big brother. When I spotted his jersey, I dashed across the field and wrapped him in the biggest hug. And for a moment, the two of usme in my band uniform and Keith in his dirty football gearstood there under the glare of the Friday night lights, feeling like stars.

The Herbert Kayton Homes public housing project, where my family lived, sat in the school attendance zone for Johnson High. I was about nine years old when we moved there. My oldest siblings were grown and living on their own by then, which left six of us kids living in the four-bedroom apartment with our parents, and we all shared one bathroom. Occasionally, one of the older siblings would move back home for a short while, making our tight space even tighter. But we always made room. We were taught that next to God family trumped all else.

My father, Jonathan Warnock, had served in the U.S. Army during World War II and was self-employed. He hauled junk, mostly abandoned cars, salvaging their metal at the local steelyard in exchange for cash. In my youngest years, he also served as pastor of a small Pentecostal Holiness church. Mom stayed at home to take care of our big family.

I mostly remember Kayton Homes as a nurturing village, even in the 1980s when the crack epidemic and the deadly HIV/AIDS virus swept into and devastated poor communities like ours throughout the country. But in a place where there were too many missing fathers, I had two devoted parents at home, and they kept church at the center of our lives. On Sundays, there were two services, the first in the morning with a short afternoon break before the evening service. A few Sundays a year were designated as Youth Sunday, and the young people of the congregation under eighteen years old conducted the entire program, sometimes even the sermon. One such Sunday night, Keith volunteered to deliver the sermon, and as I sat there, listening to him express his faith, I thought, Well, I can do that! Not long afterward, I took a turn in the pulpit, expressing my faith, to be sure, while also trying to one-up my big brother.